Julian Opie has been making art since he was 12. While his friends were misbehaving after school, he was in his bedroom in 1970s Oxford, working on one project after another, revising and remaking. That is where and when, he says, his driving need to go back to things began. He was always figuring out how to make a piece better than he had the day before. "I've been doing that ever since," he says.

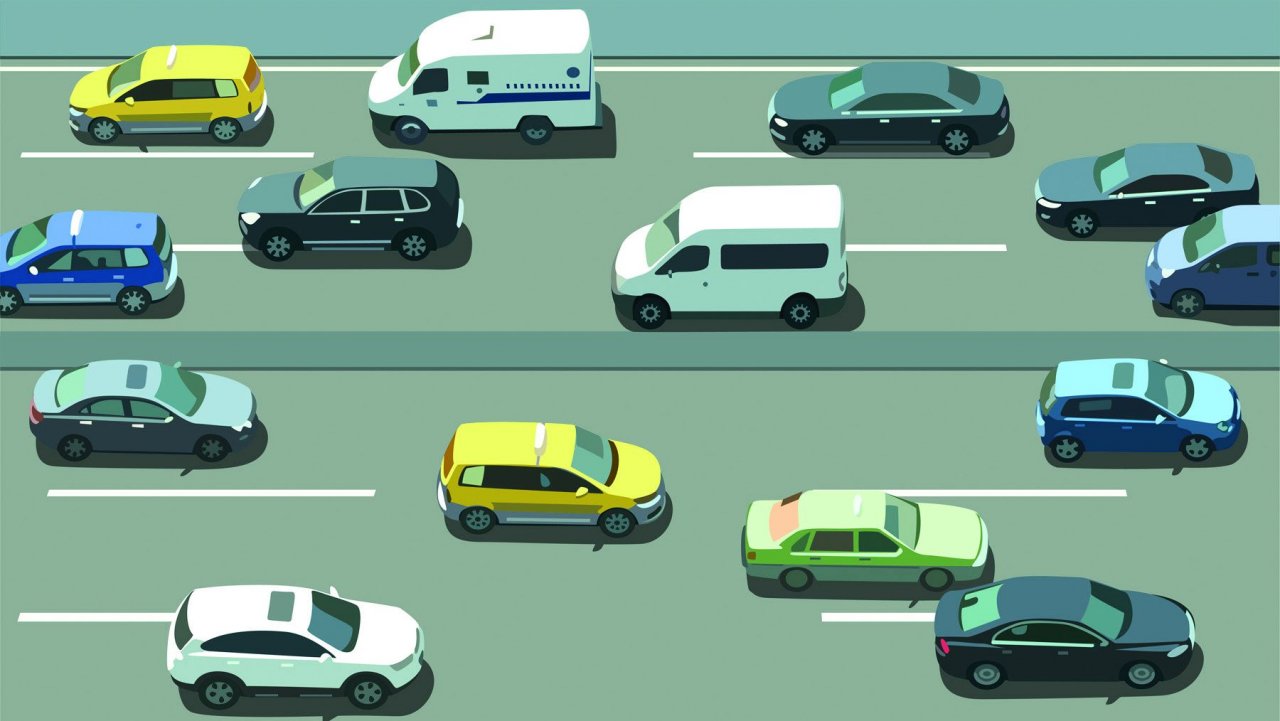

Opie, now 58, has been a success from the moment he graduated, in 1982. He'd studied at Goldsmiths University in London under conceptual artist Michael Craig-Martin, whose way of thinking, Opie says, was a close match with his own. His degree show—a multimedia combination of animated films, wall paintings, fish tanks and perfume—sparked interest almost immediately from collectors and galleries such as the Lisson, which still represents him. Opie has exhibited his paintings and sculptures internationally and reached beyond the traditional gallery audience with his animated LED outlines of human figures walking, sometimes presented on billboards on city streets, sometimes elsewhere—as with the huge, computer-generated animations that acted as a backdrop to Wayne McGregor's 2008 ballet Infra at London's Royal Opera House.

In Europe, he's probably most famous for his design for the Best of Blur album cover from 2000. Its digitally produced graphics of the band's four members (pink skin, scribbled hairlines, black dots for eyes) were simple and vital. Faces that got in your face, they summed up a whole decade of pop posturing and cemented his position as one of Britain's best-known artists. "I've been lucky," he says. "I never really needed to get a job."

When we meet, though, on a drizzly February morning in east London, he's deep in planning mode for his first major solo show in China, which opens in late March at the slick new Fosun Foundation exhibition space in the Bund Finance Center, Shanghai. David Tung, Asia representative of the Lisson Gallery, feels this is the right moment for Opie to make his move into China. "There has been tremendous change in the cultural landscape in the past few years," he says. "There is great ambition for new [Chinese] institutions to position themselves in the global conversation of contemporary art." New auction houses, private museums and commercial art fairs are launching all the time, enhancing the opportunity to sell—and buy. "Chinese collectors are learning fast and moving faster," says Jehan Chu, an art adviser based in Hong Kong who works with some of China's most prominent collectors. "They can be seen at all the top events, from Venice to Art Basel, snapping up works from Joan Mitchell to Jonas Wood." With this show as a launching point, Opie is making a bid to be part of a powerful art market with a growing interest in Western artists.

The studio where Opie is preparing to meet his new Asian audience is an unassuming four-story building in east London. The space, much like his work, is uncluttered: white walls, wooden floorboards. Opie opens the door wearing jeans and a gray polo shirt and introduces the team of 14—technicians, fabrication specialists and studio and communication managers—that helps execute his ideas. Everyone seems happy, energetic; perhaps a result of Opie's easy charm.

He's an attractive man, with an open face and a gaze that draws you in; despite this, he prefers not to be photographed. He takes me to his "hideaway," a high-ceilinged room on the top floor, filled with his meticulously arranged collection of prehistoric and medieval art. Egyptian sculptures stand among Roman busts and helmets; 19th-century silhouettes are piled up on a stool. It's perhaps a surprising collection to belong to an artist who so often works in digital formats. "I like to surround myself with other people's work; it gives me confidence rather than analyzing my own," he says.

He shows me a 3-D-generated plan on his computer that displays the Shanghai exhibition space in exceptional detail. More than 50 works, from wall paintings to mosaics, tapestries and animations, will be shown across two floors. Opie is keen to build the momentum slowly for visitors as they move through the show. "There's a mentality to [viewing] an exhibition," he says. "You're full of energy when you start; you're also full of suspicion. You're thinking, Is this boring? Do I really like this artist? Initially, [I] don't want to show too much—but at the same time, I want to intrigue." He will be uploading this virtual display to his website so that anyone can visit the exhibition without actually being there physically. It's both a simple concept and a typical Opie-ism: You wonder why no one else is doing it.

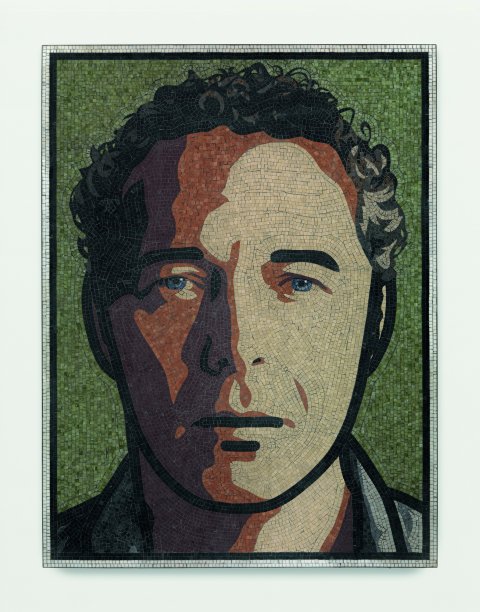

When you look at the range of exhibits, it's clear why Opie is celebrated for his mastery of diverse media, from LED and digital formats to sculpture and paint. But his real strength is in his ability to look at the world with extraordinary clarity, getting to the nub of complicated subjects by stripping out unnecessary detail. His work is pared back, distilled—and yet it has a distinctive language that is instantly readable. Take Country Road , Danielle or Necklace Man : a black outline, blocks of color and not much more—but they are alive. "That's the kind of way in which I understand art: being simple and essential. Anything other than that seems like a waste of time," Opie says.

There's humor too, a lightheartedness. Pilot , Doctor and Flight Attendant are part of a playful series of brightly colored paintings in the upcoming show, portraits of anonymous people whom Opie has observed and photographed anonymously out on the street, labeling them with imaginary professions. He has no idea what the people in the paintings actually do: "You make judgments when you [look at] people fast; you think they might be this, they might be that." Opie is having a laugh, but he is also asking questions about how we look at things and what assumptions we make. The short, snappy titles are by design. "You don't want names like 'Rising Phoenix 6,' pretentious titles that suggest there's more there than there is," he says. But he remembers a time when he used to give his works much longer names. "I would write an essay about what was going through my mind," he says. "But that was mostly to annoy curators."

Opie has shown work in China once before, though as part of the U.K.'s pavilion for the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai. He admits he has found the experience easier this time, which he puts down to Shanghai's rapid development, cultural and otherwise. "I saw a much more varied place, this time older bits and newer bits—it's changed a great a deal." Changing tastes might also play a part. "Every culture starts [by buying] their own heritage," says Patti Wong, chairman of Sotheby's Asia. "For the Chinese, it's their ceramics, paintings and ink on paper, but as they travel, they see more of the world, they visit museums, and their interests [in art] broaden. It's a natural progression." Fabien Pacory, an art adviser, curator and entrepreneur who has been based in Guangzhou for 13 years, agrees. "The art market in Hong Kong is well established, but mainland China is different; you can now feel that something is happening," he says. "There's a new wave of collectors who are young, fresh and active; they bring a new perspective." But information is key. "We don't have the social media that's available in Europe and America thanks to heavy internet censorship, so it's often difficult to find content. The Chinese are curious; they want to discover things, but Western artists need to make more of an effort to promote their work and translate it." When Pacory searches for Opie on Baidu (the Chinese version of Google), he can find only one article in Mandarin.

So has Opie made any work for the show that is specifically aimed at a Chinese audience? "I've thought a bit about locality," he says, "because making a connection with the viewer is key. But if I felt that some element of the work would only be understood by a few, it would seem like a failure to me."

Before I leave, we talk again about his adolescent experiments with making and remaking. "I used to paint the walls in my parents' house," he says. "Sea, water, a bit of land across the middle. I did portraits too and bits of bodies." Even back then, he was making the same kind of art he does today: straightforward, logical and true. That's why the new show should succeed, as the beauty of Opie's art is in its universal language. There is an honesty and generosity to his work that draws you in—it comes with no pressure to extract a deep-rooted message. So what is it that he would like people to take away from the show? "I just want people to recognize that somebody else is alive and to feel some sort of communication," he replies. With any luck, the art will provide its own form of translation.

"Julian Opie": Fosun Foundation, Shanghai, Mar. 28 to June 10.