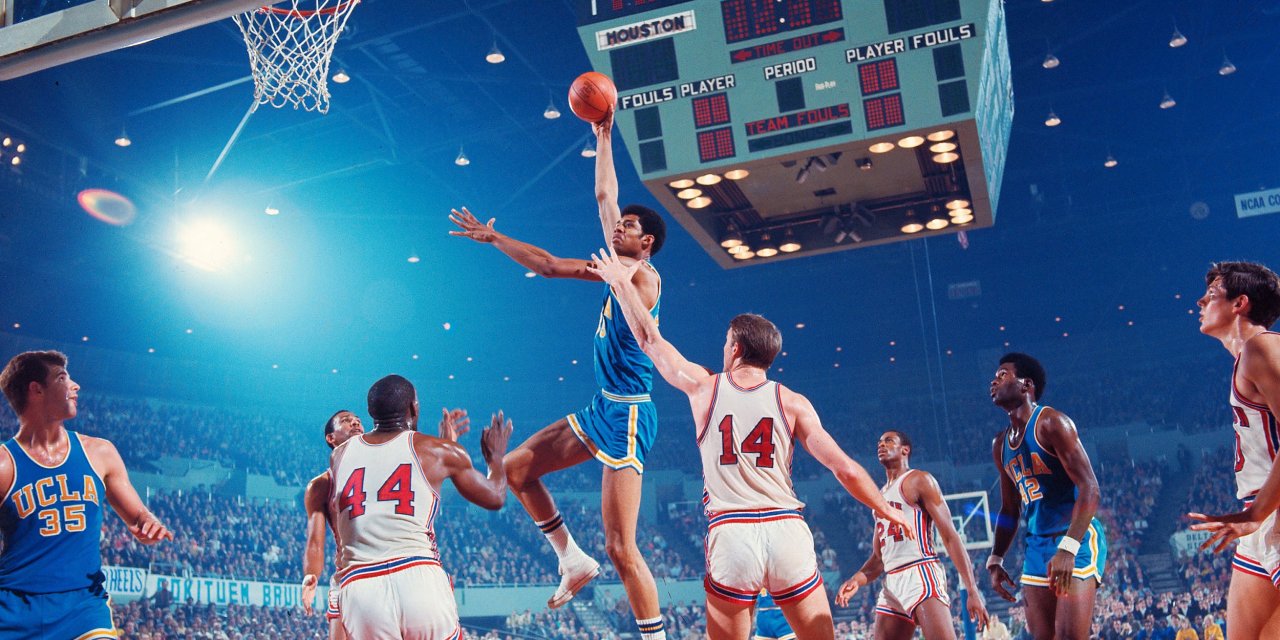

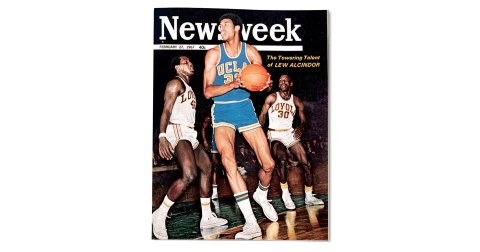

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was still using his birth name, Lew Alcindor, when Newsweek put him on the cover in early 1967. The UCLA sophomore and soon-to-be USBWA College Player of the Year was 7 feet, 1 inches of "lyrical power and mobility," sinking a record 67 percent of his shots. He would join the Milwaukee Bucks in 1969 (for a salary of $250,000), move to the Lakers in 1975 and retire from the NBA in 1989. He remains the highest-scoring player of all time.

When Alcindor came up, teams were still pretty evenly divided between black and white players, but that was beginning to change; the biggest stars—Boston Celtic Bill Russell, Philadelphia 76er Wilt Chamberlain and Cincinnati Royal Oscar Robertson—were African-American. The Celtics had the first all-black starting five during the 1965-1966 season; after winning their ninth straight title, they signed Russell as the NBA's first black coach. "We've got to make the white population uncomfortable and keep it uncomfortable," said Russell.

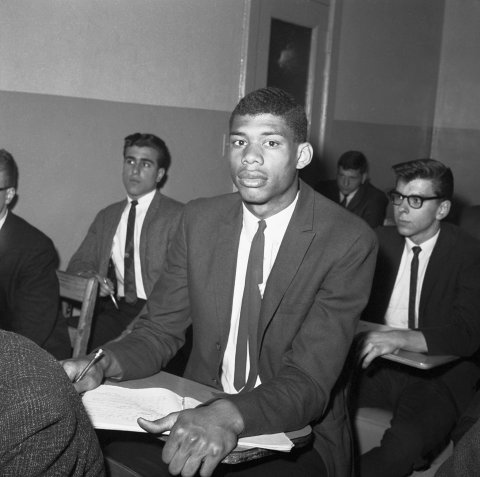

Alcindor would convert to Islam in 1969 and assume his Muslim name in 1971. But in this excerpt from Newsweek's 1967 profile, you can see the bookish man who would frustrate fans and the press with his disdain for publicity and small talk. A record-breaking phenomenon in high school (scoring 2,067 points in four varsity seasons, plus a team that lost one game), Alcindor had become the hottest NBA prospect while at UCLA, already besieged by the media. By the time this article ran, Alcindor had rejected a $1 million lifetime contract to play with the Harlem Globetrotters. "I'm interested in my education," Alcindor told Newsweek.

You can also see the beginning of Abdul-Jabbar's lifelong commitment to social justice and equality on and off the court, as well as the patronizing racism entrenched in a mainstream magazine and in sports—a mindset that continues to challenge African-American athletes. —Mary Kaye Schilling

Towering Promise

An excerpt from Newsweek's 1967 profile of the young Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, legend in the making

As an only child growing up in New York's Dyckman housing project north of Harlem, Alcindor worked out his own routine for doing homework. It involved the comforting background music of jazz artists Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Charles Mingus and Miles Davis.

"When he started playing his records [at UCLA]," says Lew's mother sympathetically, "the kids just naturally flocked to his room. But he just wanted to relax and study. It's not that he's a moody child. He's not a loner." This year, however, Alcindor tried sharing an off-campus apartment, then moved into a private home in Westwood.

Like a normal boy 2,500 miles from home, Alcindor misses his family and friends. "If they could just transplant the UCLA campus to Times Square," he told a New York friend wistfully. And the serious Alcindor's disenchantment with sunny Southern California continues to grow. "California is playing a game on the rest of the country," he says unhappily. "Too many of these people are acting all the time as if they're on TV." Clearly, he finds them artificial.

Alcindor himself is in the spotlight much of the time now, and his feelings are ambivalent about its increasingly harsh glare. More and more he finds himself exposed to a fickle, often fatheaded public. At 19, he has not yet learned how to tune out triteness. He still seethes when strangers gape and ask, "How tall are you?" (Alcindor refuses to answer) and "How's the weather up there? (he must have heard the question 5,000 times). Once, a middle-aged woman in New York City poked and prodded him with her umbrella as if he were a strange furry animal on her patio. This season, another woman crept up to him in the lobby of a Seattle motel, shouted, "Hey!" and exploded a flash camera in the startled teenager's face.

"They think I'm moody and reclusive here," Alcindor complained to Newsweek sports editor John Lake, "but under these circumstances that's the only way I can be." The conditions that disturb him most, however, are not the cliché spouting or even umbrella-jabbing. They are the conditional acceptances, the subtle quotas and the outright denials of human equality that—in one form or another—still confront most Negroes each day of their lives.

People always stare at 7-foot Lew Alcindor. Except when he is with Asian or African-American friends on the UCLA campus. ("Height doesn't make any difference to them; they're interested in you as a person.") Alcindor is conscious of the stares. But one friend reports that when Alcindor occasionally goes out with a white girl, many of the stares become glares.

"It fences me out," reasons Alcindor, "it's bad. The South is in Montgomery. But the South is also in Cicero, Illinois. The South is in Great Neck, Long Island. The South is in Orange County, California. It's everywhere."

Alcindor is quite convinced it was "Southern justice" that brought a policeman blustering into the argument when he and some Negro friends disputed the check in a Westwood diner one night not long ago. "He just naturally assumed I was the transgressor," says Alcindor bitterly. His working vocabulary includes a number of five-dollar words. But it also includes such phrases as "the Gestapo thing" and "the ghetto." The more he reads (Alcindor is majoring in history), the more he sees life off the basketball court, the more Alcindor burns with resentment and racial pride. Still no outspoken advocate of Black Power, he nonetheless finds much in common with football's Jimmy Brown, basketball's Bill Russell and boxing's Cassius (Muhammad Ali) Clay—older Negroes who first established themselves as sports superstars, then revealed how deeply they resent the role of the black man in U.S. society.

Alcindor delighted Clay at their first meeting four months ago outside a Hollywood restaurant. "Salaam Alaikum," the youth greeted the heavyweight champion. Surprised, Muslim Clay delivered the proper response—"Alaikum Al Salaam"—then reverted to another role and squared off against the huge collegian. "I wouldn't want to fight you," he wisecracked. "You got the reach on me."

Alcindor's intellectual reach might have impressed Clay more. He is reading the Koran; he calls The Autobiography of Malcolm X the most significant book in his life to date.… He also finds validity in the anti-white emotionalism of playwright and essayist LeRoi Jones, whom he met in a Harlem coffee shop. Indeed, the gum-chomping, bored-looking basketball whiz has much on his restless mind that most Pauley Pavilion fans would find highly disturbing.