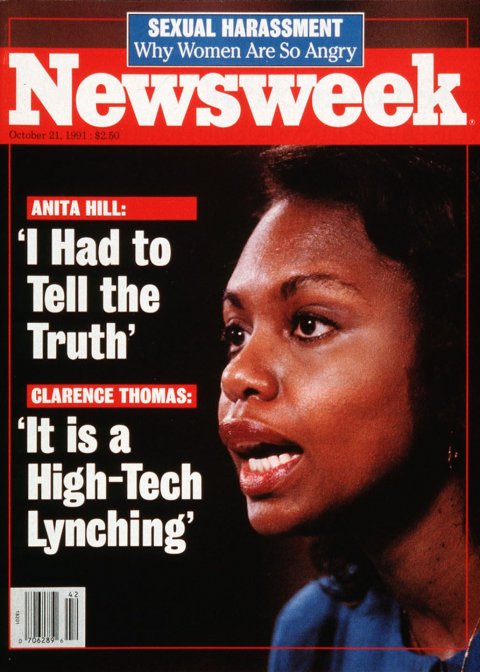

On September 27, Christine Blasey Ford testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee regarding her sexual assault allegations against Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh. It was eerily familiar, as if no time had passed between 2018 and 1991, when, nearly to the day, Anita Hill testified regarding alleged sexual harassment by Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas. Again, millions tuned in to watch as Ford—with a poise reminiscent of Hill's—recalled a harrowing attack during a high school party, as well as the years of emotional damage that followed. Kavanaugh, much like Thomas, strenuously denied all of the allegations, with palpable rage and some tears.

There were more disturbing echoes. Over two decades later, the Republican senators facing Ford were still all men. Once again, hatred was directed at the accuser, who received death threats. A woman speaking up, it seemed, was still a target for condemnation, as well as a tool for partisan politics.

On October 21, 1991, Newsweek published a cover story by David A. Kaplan on the Hill and Thomas proceedings. An accompanying article, "Striking a Nerve," examined how sexual harassment "is a fact of life for millions of American women. When Anita Hill talked last week, they heard themselves—and they're fed up with the fact that men don't get it." Also included: "Why Women Are Angry," and essay by Laura Shapiro. Among her points was that the rage ignited by Hill's charges "had been smoldering for years, fed not only by the common experience of sexual harassment but all the outrages large and small that make this country a radically different place for women than it is for men."

There was notable progress in 2018. Ford was believed by many and praised for her demeanor. Joe Biden, a Democrat who had served as the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee in the '90s (and came under criticism for his aggressive questioning of Hill), called her testimony "courageous, credible." No one implied that Ford's claims were adapted from The Exorcist (as Senator Orrin Hatch did of Hill) or that she had "introduced sleaze" to the Senate. And this time, the Judiciary Committee agreed to a one-week supplemental background check by the FBI, thanks to a last minute change of heart by GOP Senator Jeff Flake of Arizona—a flip that came thanks to an emotional encounter, in an elevator, with a sexual assault survivor incensed by the treatment of women like her. Captured on video, it went viral.

It makes you wonder if the full might of social media would have shifted sentiment in 1991. Thomas's lifetime position was confirmed by a slim margin—in a 52-48 vote—and more clamor might have hurt his chances. Certainly, Hill would have felt less isolated with a #MeToo army of support behind her.

That October 21, 1991, cover story—reprinted below—is both fascinating and deeply troubling. It makes clear that, 27 years later, we still have a lot of work to do. —The Editors

Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill sat under the same hot white lights at the United States Senate, a damaged man and an injured woman demanding justice. Two parallel lives that had looked exemplary suddenly collided over an ugly story of sexual harassment. Poised and intelligent, Hill said that when she had worked for Thomas a decade earlier, he harassed her with barnyard talk of porn flicks, group sex, bestiality and his own sexual prowess. Jaw taut with outrage, Thomas categorically denied all of it, arguing that a mob from the sewer was out to lynch him. One witness was telling the truth, the other was lying; one was a victim, the other a hypocrite. But which was which?

As the needle of credibility swung back and forth between the Supreme Court nominee and the young professor of law, the country sat glued to television, watching a spectacle that was at first riveting, then depressing, and ultimately revolting. Public officials babbled over breasts, pubic hair, the meterage of penises and the exploits of a porn star called Long Dong Silver. The accused sat glaring, his wife at his side weeping at the raw details. The accuser listened while a panel of 14 men wondered aloud whether she was just a fantasist who had made it all up. To watch was to become a voyeur. The X-rated antics were hard to stomach—and harder to turn off.

Never before had the issue of sexual harassment welled up into such a large and emotional public forum. There was no way that roughly 4 million years of male supremacy was going to yield to Robert's Rules of Order. But men nodding as senators demanded to know why any infraction 10 years old should ruin Thomas's career also found themselves uneasily searching their own memories for that furtive grope, off-color joke or idiotic leer they had once considered irresistible. Women admiring Hill's nerve recalled moments they or someone they knew had been in Hill's shoes, the occasions they had remained silent. It happened all the time, they said; the only reason men didn't get it was because they never tried.

The performance of the Judiciary Committee, with posturing senators, staffers and reporters tumbling over one another, raised a nasty question: Had the process itself run amok? There had to be a better way to pick a Supreme Court justice. "The judge was wronged. Anita Hill was wronged. The process was wronged," committee Chairman Joseph Biden conceded. Was this the best the system had to offer? The nation had received a seismic jolt, but everyone wound up feeling soiled.

Anatomy of a Debacle: Behind the Scenes

The Thomas-Hill hearing was one of those remarkable moments in the political life and social consciousness of a generation. Far more was at stake than a seat on the Supreme Court, more than deciphering what, if anything, happened between a man and a woman 10 years ago. The Senate itself, 98 percent male, was on trial: Had it almost let a brute slip his way onto the court? Or was it an accomplice in a despicable case of character assassination?

On every network and for 21 hours, the two witnesses, separately, offered their polar versions to the Judiciary Committee. First in the dock was Thomas, who unequivocally denied that he had sexually harassed Hill when they worked together from 1981 to 1983 at the Department of Education and then the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). He had dismissed his White House handlers, and it showed. In a tone of fury and rue, he skewered the senators. "This is Kafkaesque. Enough is enough," he said. "I have not said or done the things that Anita Hill has alleged. God has gotten me through...and he is my judge." It was a peroration that made the president of the United States [George H.W. Bush] weep.

Then Hill offered her excruciating account. In lurid detail, she described Thomas as a boss who pestered her for dates and spoke graphically about pornography, bestiality, rape and his skills as a lover. "He talked about pornographic materials depicting individuals with large penises or large breasts involved in various sex acts," she testified. The "oddest episode," Hill said, occurred when he was drinking a Coke in his EEOC office. "He got up from the table at which we were working, went over to his desk to get the Coke, looked at the can and asked, 'Who has put pubic hair on my Coke?'"

When Thomas returned to the witness table shortly after 8 p.m., he was even angrier than he had been in the morning. "This is a circus, it's a national disgrace, and from my standpoint as a black American...it's a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks," he said. "It is a message that...you will be lynched, destroyed, caricatured by a committee of the U.S. Senate rather than hung from a tree."

Such virulent words were the culmination of a week unprecedented even in the seen-it-all-before culture of Washington. Just a Sunday ago, Thomas's confirmation looked like a lock. How his nomination blew apart—at the warped speed only American politics can move—is a story about stupidity and luck, betrayal and indifference, cynicism and leaks. Rarely have so many politicians miscalculated so badly in such a short amount of time.

The Sleaze Hunters

In the beginning, as it inexorably seems to be under the new hardball rules of politics, there was the search for sleaze.

Last July, as Clarence Thomas stood beside President Bush on a Kennebunkport lawn to accept his nomination, Republicans could hardly contain their glee. Once more, Bush had outfoxed the Democrats. How could white senators vote against a black nominee who, though conservative, had risen from the depths of Southern poverty. Liberal interest groups, with only the scalp of Robert Bork to show for all their judicial headhunting in recent years, nonetheless held out hope. At least it was worth the effort, given that the 43-year-old Thomas might serve on the high court into the 2030s. Since his controversial legal views alone were unlikely to sway senators to vote him down, liberals went out to scour Thomas's personal life. Journalist Juan Williams had done several profiles of Thomas over the years. In a Washington Post op-ed piece last week, Williams revealed that all summer long he was called by eager Senate staffers seeking "anything on your [interview] tapes we can use to stop Thomas." Did he ever take money from the South African government? Did he beat his first wife?

Nothing surfaced—until they got lucky. In August, Nan Aron, head of the Alliance for Justice, which opposed Thomas, got a call from a person saying Thomas had harassed an employee named Anita Hill in the early '80s. The male caller, whom Aron says she knew, had been a classmate of Hill's at Yale Law School. It isn't known whether he was calling at Hill's behest or even with her knowledge. In any event, Aron passed along the information to the staff of Democratic Senator Howard Metzenbaum, the only member of the Judiciary Committee to vote against Thomas's successful nomination to the federal appeals court in Washington in 1990. Metzenbaum seemed to be the most likely senator to pursue the tip. It was a long shot.

Juicy charges percolate up at the last minute in many Supreme Court fights, and they usually don't pan out. Metzenbaum's Labor Committee staff went forward. On September 3 or 4, a female aide phoned Hill. According to Metzenbaum's chronology, the call was only part of a routine inquiry to three women who worked with Thomas at EEOC. Hill, a law professor at the University of Oklahoma, was asked about such legal issues as gender discrimination. The aide mentioned rumors of sexual harassment, but Hill offered nothing. On September 5, a second Labor aide, Ricki Seidman, called Hill. Seidman works as an investigator for Democratic Senator Ted Kennedy, who, like Metzenbaum, sits on both Labor and Judiciary. This time Hill said she needed to think about whether she would discuss harassment.

Four days later, Hill agreed to talk. Seidman referred her to a Metzenbaum lawyer named James Brudney, who had attended Yale with Hill. The next day—when the first round of Thomas's confirmation hearings began—Hill detailed her accusations to Brudney. Trouble was, Brudney wasn't on the Judiciary staff. So, after consulting Metzenbaum, he forwarded the charges to Harriet Grant, chief of nominations for Judiciary. On September 12, in two calls, Hill repeated her story to Grant.

The Fumble

The ball was rolling—with one roadblock. According to Biden, Hill demanded confidentiality, that Thomas not be informed of her charges and that the FBI undertake no investigation. Hill told Grant that she wanted to share her concerns with the committee to "remove responsibility" and "take it out of [her] hands." Biden decided not to tell other committee members of the allegations. Only he, Metzenbaum and Kennedy knew at this point.

Over the next week, as the Thomas hearings continued, Hill spoke to no one at Judiciary. Grant did receive one call—from Susan Hoerchner, a Yale classmate of Hill's, who told Grant that Hill confided in her in the spring of 1981, at the time of the first alleged harassment by Thomas. Hoerchner corroborated Hill's account, reporting that Hill said Thomas caused her to doubt her own professional abilities. On September 19, Hill called Grant again. For the first time, Hill said she wanted all committee members to know her story, even if her name had to be used. Hill insisted she didn't want to "abandon" her concerns about Thomas. The day before, she had given an interview to the University of Oklahoma student newspaper. Though she made no mention of harassment, she said "there were a lot of better" candidates than Thomas for the court vacancy.

Still, she was not willing to involve the FBI, a routine step Biden demanded before the issue could go further. Hill thought it over, concluding on September 21 that she didn't want the FBI investigation because she was "skeptical about its utility." Finally, two days later, in what was at least the seventh conversation that week between Hill and the Judiciary staff, Hill said she would submit a statement of her charges to the committee and then agree to bring in the FBI. Throughout these September negotiations, some senators suspect Hill was in regular contact with aides to Kennedy and Metzenbaum, especially Brudney. Thomas's supporters point to them as the source of alleged arm-twisting on Hill. Senator Dennis DeConcini, a Democrat, says it's apparent that "a Labor committee aide was giving her advice." Similarly, the White House wonders if Metzenbaum and Kennedy staff badgered Hill into relenting on confidentiality.

Hill faxed her four-page statement to the committee on September 23. Biden passed it on to the White House and FBI. This was the first the Bush administration had heard of Hill's claims. White House counsel C. Boyden Gray ordered the FBI to investigate. While the president was briefed, he and his advisers perceived no ticking time bomb; they assumed the charges would prove false. FBI investigators questioned Hill the same day in Oklahoma. Over the next two days, the FBI also talked with Hoerchner and Thomas himself. The nominee learned of the allegations when the FBI showed up at his suburban Virginia house to interview him; he denied the allegations. The FBI completed its report on the 25th. Sources who've seen it say it reads like a bad wire story, a collection of he-said, she-said quotes that reaches no conclusion. Nonetheless, the White House and Republican senators would eventually claim publicly that the report proved Hill wrong.

The White House sent Biden the report, along with a memo from Ken Duberstein, the former Reagan chief of staff hired to manage Thomas's confirmation machine. Biden and his defenders say Hill's desire for confidentiality precluded further investigation. "Talk about sexual harassment," says a friend of Biden. "How could you pressure this woman?" Of course, he could have called Hill to Washington so that he could meet with her privately to assess her credibility. He could have summoned Hill and Thomas into a closed committee session, though that surely risked a leak. Or he or any other committee member with knowledge of the allegation could have asked for a delay in the vote, pending an attempt at further inquiry.

Biden made one obvious mistake. It was on the night of September 25, after he had received the FBI report. Admittedly under pressure from the White House to get Thomas confirmed before the Supreme Court started its term October 7, Biden scheduled the Judiciary vote on Thomas for September 27. Yet he knew he wouldn't be briefing most of his fellow committee Democrats on the Hill charges until the 26th. That gave colleagues little chance to ask for a postponement of the vote. Biden says he or an aide verbally briefed each of the seven Democrats on the 25th or 26th, and that each had access to both the FBI report and Hill's statement before the vote on Friday the 27th.

But some of the senators say Biden gave them short shrift; at least one was never told of the report, Newsweek has learned. Moreover, Hill's statement was given to the other committee Democrats just 20 minutes before the vote—while Biden was on the Senate floor announcing his opposition to Thomas even as he vouched for his character.

Biden wasn't the only one who dropped the ball. Newsweek has learned that Senator Strom Thurmond, the ranking Republican on Judiciary, didn't tell all the five GOP members of the allegations. Arlen Specter, a wavering vote, first heard about Hill on Thursday (from two Democratic colleagues); he met with Thomas for 30 minutes the morning of the vote. Thurmond staffers told aides to Hank Brown of the charges but said it contained "nothing of significance," according to Brown. Charles Grassley learned of Hill in newspapers more than a week later. Paul Simon, a Democrat, apparently is the only senator who spoke to Anita Hill prior to the Friday vote. Simon received a call from one of Hill's friends asking that he phone her. When they spoke on Thursday, Hill asked Simon to give her statement out to all 100 senators but keep it otherwise confidential. Simon suggested that a leak would inevitably occur, so Hill decided against distribution.

Despite the 7-7 deadlock by the Judiciary Committee, Thomas's prospects for confirmation were excellent. The week of September 30, moderate Democrats began declaring support. By Friday, Thomas by all counts had enough votes to win. Going into the weekend—with a full Senate vote scheduled for Tuesday—what could go wrong? "We thought this was in the bag," says a senior administration official.

The Bombshell

Sunday is a sleepy day in the capital. Other than churchgoers, the only folks in stockings and ties seem to be on David Brinkley's show. It was this calm that Newsday and National Public Radio disturbed on October 6 when they ran stories on Hill's accusations. Actually, the administration and Thomas knew the night before that the Hill story was about to break. Duberstein turned on the spin cycle. Senator John Danforth, the Missouri Republican and Thomas's chief patron, held an impromptu press conference at home. They had no idea this bombshell would turn out to be thermonuclear, with a chain reaction to match. Danforth should have listened to his wife. "I dismissed it and she didn't," he acknowledged to The New York Times.

On Monday morning, the Democratic Senate leadership maintained the vote on Thomas would proceed as scheduled the next day. The White House maintained a low profile, though aides did accuse the Democrats of a smear campaign. The assumption that the Hill charges would go away, however, evaporated when Anita Hill went on television. In a one-hour press conference beamed from Norman, Oklahoma, Hill may have killed Clarence Thomas's career plans for the next 40 years. She was credible, she was articulate, she was poised—even in the face of enough menacing phone calls at home that she notified the police. "I resent the idea that people would blame the messenger for the message, rather than looking at the content of the message itself," she said. The political seismographs in Washington recorded the effect: Women's groups mobilized, phones blew off the hook in the Senate.

Still, the White House continued to believe Thomas had the votes. Several key senators, Newsweek has learned, told administration officials they needed some evidence, as one official put it, to "hide behind...something that would allow them to say, 'I considered his story and hers, and he's telling the truth.'" Gray's office lined up women who worked with Thomas at the EEOC who would sing his praises. At 4 p.m., Bush's team gathered to reassess the mess. No women were present. They concluded that, because Hill continued her relationship with Thomas long after she left the EEOC, senators could be convinced that she could not possibly have viewed his alleged behavior as very serious.

Leak hunting became an obsession for Republican senators. Their suspicion centered on Metzenbaum, Kennedy and their staffs. Hatch directly accused Metzenbaum—who denied it—and he later apologized. Brown said he intends this week to ask for the appointment of a special counsel. The bad blood spilled over to the Democratic staffs. Newsweek has learned that one meeting of all the chief lawyers for the Democratic members of Judiciary turned into a shouting contest. At issue was Biden's vivisection in the press by these lawyers being quoted anonymously. "People don't trust each other anymore," said a participant.

Thomas was active on his own behalf. Late Monday, in one of their many phone conversations that day, Thomas told Danforth that Hill had called him throughout the '80s. Danforth tracked down Thomas's former secretary, who told him there were phone logs of Thomas's messages. That night, Republican Senator Alan Simpson read from them on Nightline—there were 11 calls over a six-year period—to bolster the case that Hill hardly seemed too upset with her former boss. The next day the logs were fed to the press. "We thought the logs would put an end to it," says a senior administration official. "Little did we know."

The Revolt

On Tuesday, Specter stunned the White House by asking to postpone the vote that night. Democrats warned they would vote Thomas down if forced to vote. The key protest may actually have been choreographed over at the House of Representatives. Around midday, seven female members of the House marched to the Capitol room where the Democratic senators were in caucus. If the boys didn't "get it" before, they did now. The symbolism was palpable. "The thing everyone miscalculated was the reaction of the women, the girls' vote," says a Bush adviser. "The Senate crumbled before our very eyes." Two hours after the scheduled vote and a splenetic day of C-SPANing, senators formally agreed to delay the vote by a week.

That left only two and a half days to prepare for the new round of Judiciary hearings, but that was plenty of time to fan the flames. Bush was enraged and vowed war on the Democrats after the curtain went down on the Thomas matter. Some of the Democrats continued to wage war among themselves. And on Thursday, the news that Thomas supporters feared most: Another woman, journalist Angela Wright, had come forward to claim Thomas had harassed her. Yet, even with that revelation, nobody could have anticipated the perverse spell on Friday and Saturday of the Hill-Thomas showdown.

Under the bright lights, ripped bare before the American public, Hill and Thomas were both effective witnesses. She offered compelling specificity; he, at times in tears, spoke passionately of a process out of control, of a reputation and a family shattered. The Republicans went after her for being inconsistent and opportunistic, and suggested her reference to "Long Dong Silver" was inspired by a court case in Kansas. The Democrats, if gingerly, kept asking him how on earth his accuser could make up so much. Hill and Thomas both had legions of character references. She even volunteered to take a polygraph.

Like great drama, though, there will be no objective truth. In the end, the stories of Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill are irreconcilable, unless one of them capitulates and owns up to perjury. The Senate has an impossible choice. Either way, it will commit a terrible wrong. In his closing remarks to Thomas Saturday night, Biden said "process" wasn't the problem. That was his response to Hill and Thomas, who had managed to agree on one thing: They were treated miserably. Biden was right only in the sense that the process led to an admirable result—awareness about harassment.

But what of the way we conduct our national soul-searching? Sunshine may be a disinfectant; it can also be blinding. From the way Hill's allegation emerged to the way it played out in prime time, from the insensitivity of the senators to the humiliation of two people, the Thomas spectacle hardly is an endorsement of freewheeling politics. The public was mesmerized by the show, yet shuddered at the indignity of it all. Politics has become pathology.

Reported by Bob Cohn and Ann McDaniel in Washington, Peter Annin in Oklahoma and bureau reports.