After more than 50 years being denied access to a cellar on Thomas Jefferson's Virginia plantation, archaeologists finally allowed on the premises have discovered the remains of stoves where James Hemings, Jefferson's enslaved chef, prepared meals.

The stoves were uncovered during 2017 excavations of the cellar in the Monticello plantation's South Pavilion, the oldest brick building on the estate, Live Science reported. Jefferson lived there for a short period with his wife, Martha—who was also Hemings' half-sibling, according to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

The cellar was previously out-of-bounds for archaeologists so that the space could be converted to bathrooms for tourists ("That was, in retrospect, a bone-headed decision," Neiman told Live Science.) After gaining access, archaeologists dug up thousands of artifacts, including pottery and glass bottle fragments, animal bones and toothbrushes, according to Live Science. Below that layer, they uncovered the brick kitchen floor, including what remained of the fireplace and four stew stoves.

James Hemings was born in 1765 and legally became Jefferson's property in 1774, according to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. An immensely talented chef, he was responsible for the spread of French cuisine to America, including creme brulee, merengues, whipped cream and macaroni and cheese.

"His trajectory was pretty extraordinary," Fraser Neiman, the director of archaeology at Monticello, told Live Science. "[This is one of the] really rare instances where we can associate a workspace and artifact with a particular enslaved individual whose name we know."

At age 19, Jefferson brought Hemings with him to France, where he trained at the elite kitchen of the historic Château de Chantilly, according to The New York Times. French law held that any slave that stepped onto French soil could be freed if they chose to legally pursue that option. Hemings, along with his sister, Sally, did not. Different reasons have been explored for why they chose to return to slavery, but according to NPR it's likely they didn't want to remain in France, separated from the rest of their family.

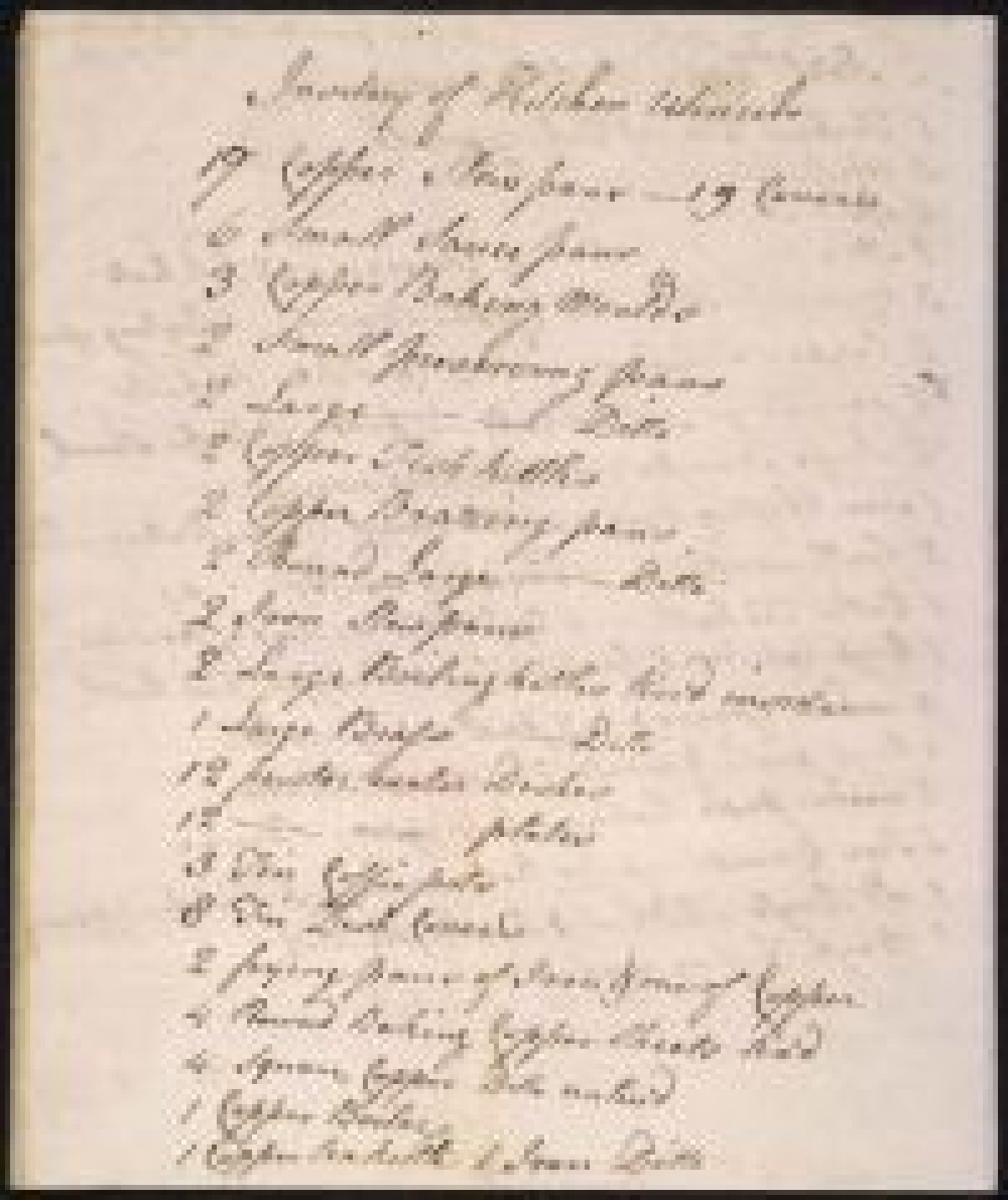

In 1796, at the age of 31, Hemings became one of just two Jefferson slaves to negotiate his freedom, according to NPR. Before departing Monticello, he left behind what, according to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, is his only material legacy: an inventory of kitchen utensils and four recipes. Hemings committed suicide in 1801.

"We're thinking that James Hemings must have had ideals and aspirations about his life that could not be realized in his time and place," Susan Stein, senior curator at Monticello, told NPR. "And those factors probably contributed to his unhappiness and his depression, and ultimately to his death."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kastalia Medrano is a Manhattan-based journalist whose writing has appeared at outlets like Pacific Standard, VICE, National Geographic, the Paris Review Daily, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.