🎙️ Voice is AI-generated. Inconsistencies may occur.

The photographer Paul Strand was a great artist of the painstaking, politicised kind; he was no fleet-footed Surrealist, smitten by the beauty of a chance encounter between a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table, nor a proponent of Henri Cartier-Bresson's "decisive moment": his preference for long exposure times, he pointed out, made for a pretty extended moment. Strand, who is the subject of a major retrospective in Madrid, was "thick and slow", said his friend, artist Georgia O'Keeffe (she meant weighty and plodding, rather than stupid); even his jokes were elephantine, according to a 1974 New Yorker profile, and "days, or even weeks, in the making". His is a monumental art, as imposing as the JP Morgan building in his great 1915 picture of capitalism, Wall Street, and as solid as the Irish washerwoman he slyly photographed using a hidden lens on a camera whose dummy lens appeared to be pointing in another direction entirely.

So it seems unlikely that he would have been charmed by the coincidence of his life with that of another great American photographer. Both sons of European immigrants, they were born less than two months and 100 miles apart and died 86 years later, an ocean away from where they started, but only 20 miles from one another. The other in this unlikely pairing might have been more receptive to it: Man Ray was a sometime Surrealist, a devotee of beauty in its unlikeliest and most haphazard forms, so the chance encounter of a plodder and a showman on the blood-soaked operating table of the 20th century could well have tickled his fancy.

Both were young men in the New York of the 1910s, falling under the spell of photographer Alfred Stieglitz, whose 291 gallery and Camera Work magazine were such enormous influences in avant-garde art and photography before the First World War. Both shaped the young medium to their own ends, refracting the convulsions in America and Europe through the prism of their radically different talents. Both would have turned 125 this year, had they not died in France in 1976. Ray, the child of Russian Jews, had returned to Paris in 1951 after fleeing the war for Hollywood – surely the farthest he could have gone, in imaginative terms at least.

Strand, whose parents were from Bohemia, moved in 1950 to Orgeval, just outside Paris, in disgust at the hounding of Communists and other Left-leaning intellectuals by McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee. (The FBI tracked his movements for years and at one point confiscated his passport.) "I have come to the point where I believe that any young artist who is not aware of the human struggle – economic and political – which overshadows every part of the world today is strangely outside the main currents of life," he said in the 1930s, when he was taking superb portraits and landscapes in Mexico and preparing to make a film, Redes (The Wave), about exploited Veracruz fishermen. "Yet to be an artist within those currents – well, that is the new aesthetic problem."

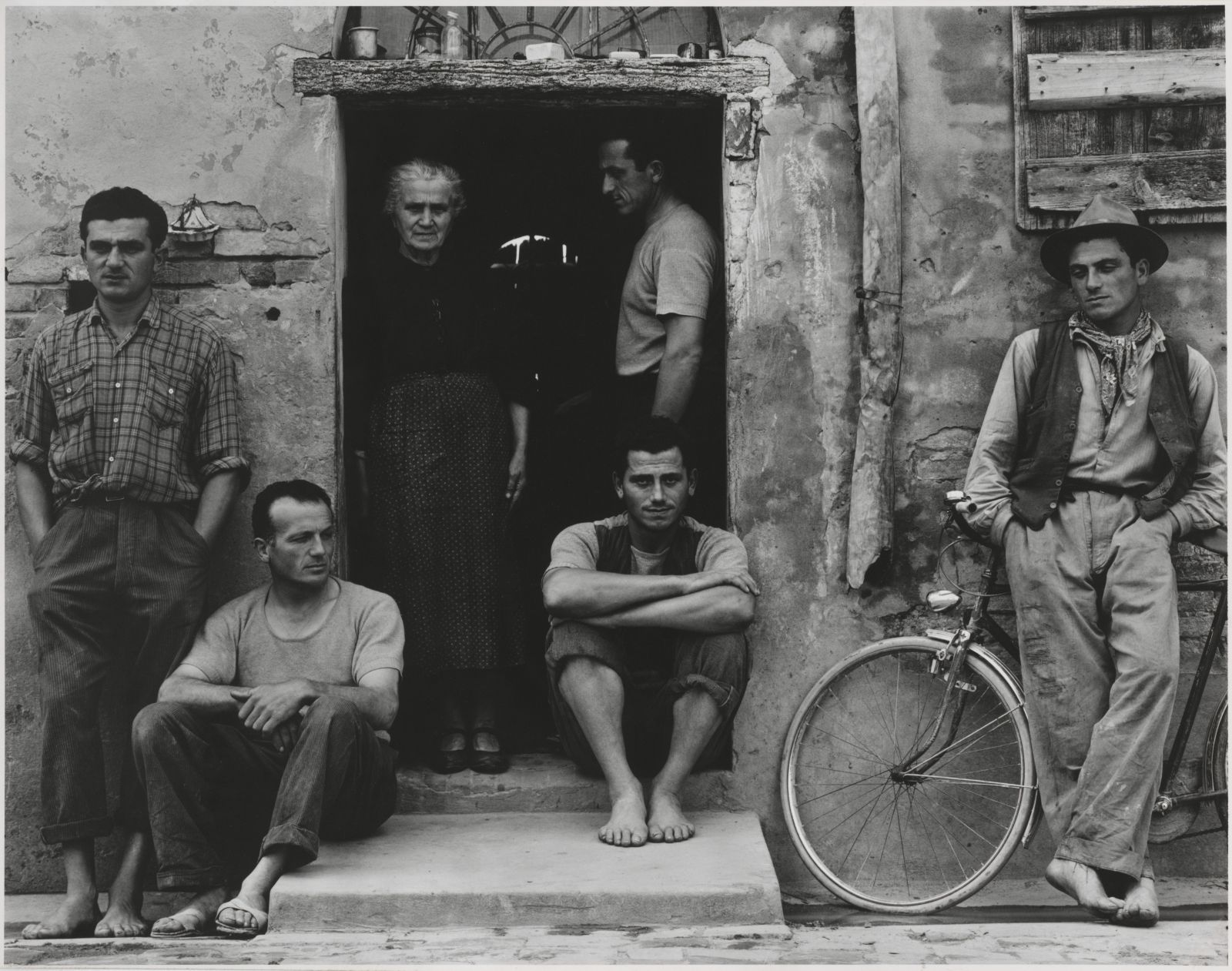

Strand liked to photograph "people with strength and dignity in their faces; whatever life has done to them, it hasn't destroyed them" and he sought out this ordinary heroism from New England to Canada and, later in life, in places as disparate as post-war Italy, the Scottish Hebrides and recently independent Ghana. Ray, who also made films, as well as painting and sculpting, was more inward-looking, experimenting with technique in the studio, inventing forms and styles that allowed him to play with content. Solarisation, in particular, which operated like a negative, turning dark areas silvery while darkening light ones, offered a liquid loveliness that stands in stark contrast to the chiaroscuro effects that Strand enjoyed achieving. Yet the similarities are more instructive than the differences: Strand's determination to get exactly the effect he wanted sometimes prompted him to wash platinum paper in a platinum emulsion then gold-tone it to intensify the blacks – a method closer to Man Ray's flamboyant experimentation than might have been expected of a realist.

In the end, that is the use to which we can put this remarkable, inconsequential coincidence: to further both artists' aim of blasting our assumptions and giving the world a sparkling, unfamiliar clarity. The Surrealists liked to use odd juxtapositions to achieve this; Strand, with patience and deliberation, laid the world bare. Placing these two men side by side is a way to do both at once: a celebration of coincidence, and also of uniqueness, that offers an extra glimmer – or ray, or strand? – of light.

When and where

Paul Strand, Master of Modern Photography, is at Fundación MAPFRE, Madrid, 3 June-23 August, then at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 19 March-3 July 2016.