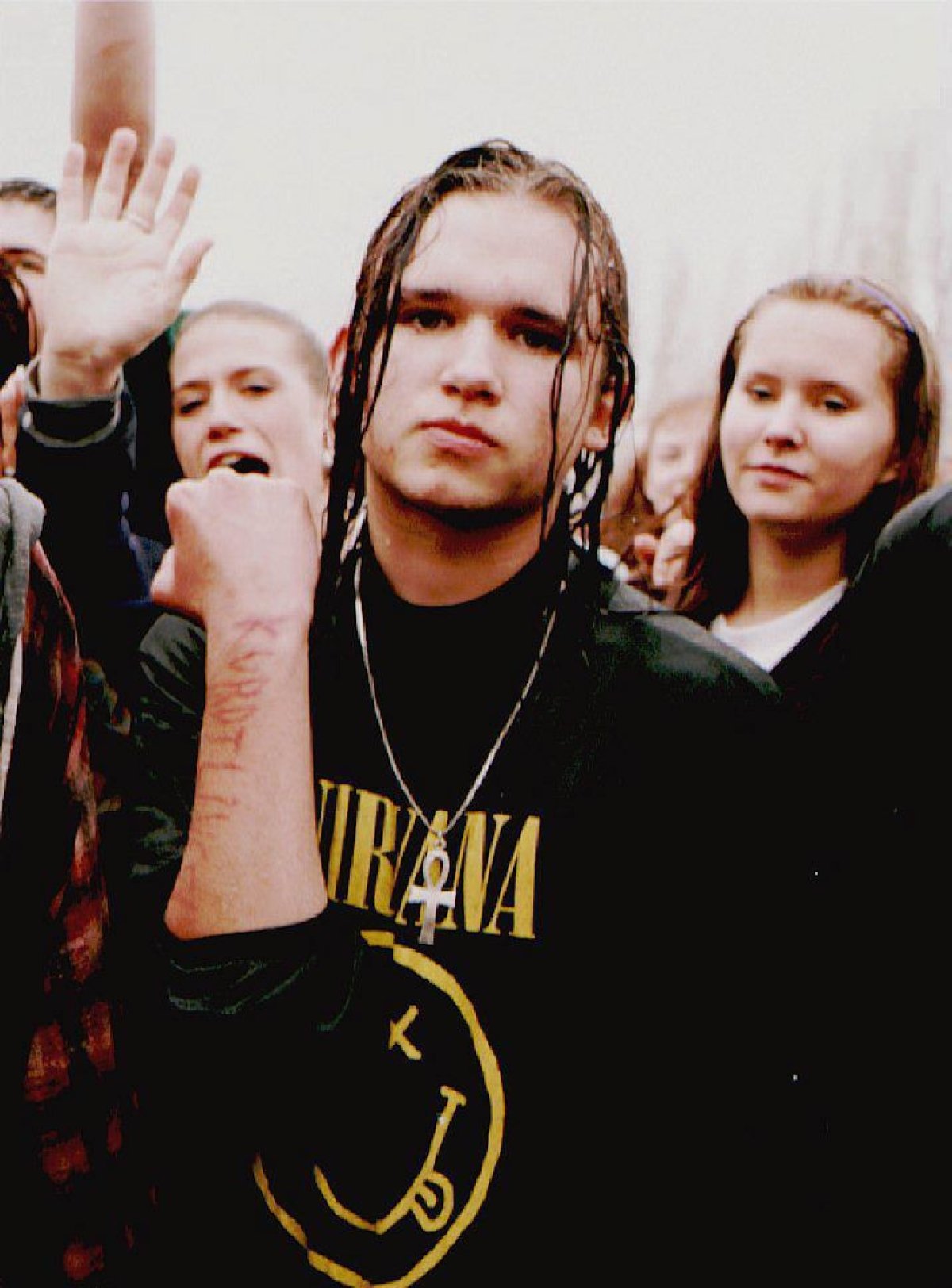

For music fans of a certain age, Kurt Cobain's April 5, 1994, suicide was as seismic, gutting and incomprehensible as the murder of John Lennon a generation earlier. Cobain, the lead singer and driving force of the band Nirvana, fundamentally altered the landscape of music and popular culture in the '90s—whether he liked it or not. (And, by all accounts, he very much didn't.) The 1991 album Nevermind and its seminal single "Smells Like Teen Spirit" put grunge into heavy rotation on MTV, initiated a flannel-and-torn-jeans fashion revolution and turned Seattle and the Pacific Northwest into a mecca for anyone (especially Gen Xers) who felt out of sync with the world around them.

When Cobain took his own life—joining a line of rock icons who died at age 27: Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison—it devastated listeners who felt they had someone, finally, speaking about, and to, them. (And didn't he swear, in "Come as You Are," that he didn't have a gun?) But fame—and being the Voice of a Generation—never jibed with Cobain or his personality. He struggled, unsuccessfully, with addiction and the consequences of Nirvana becoming the biggest band in the world. (It didn't take long for violent meatheads and bros to infiltrate Nirvana shows.) And in the weeks before his death, rumor had it he was about to break up the band and go in a different creative direction.

Newsweek writer Jeff Giles, with additional reporting by Melissa Rossi in Seattle, Charles Fleming and Mark Miller in Los Angeles and Sarah Delaney in Rome, grappled with Cobain's death and legacy in a piece published in the April 18, 1994, issue of the magazine. The piece is just as potent and relevant today, 24 years after Cobain's suicide. It makes plain how far we still have to go when it comes to issues of suicide prevention and opioid addiction—and it's a stark reminder of how raw Cobain's death still feels to anyone who remembers Kurt Loder breaking the news. — Dante A. Ciampaglia

He'd come to install an alarm system. The irony is that long before electrician Gary Smith found Kurt Cobain's body, it was clear that what Nirvana's singer really needed protection from was himself. Cobain wasn't identified for hours, but his mother, Wendy O'Connor, didn't need anyone to tell her that it was her son who was found with a shotgun and a suicide note that reportedly ended, "I love you, I love you." The singer had been missing, and his mother had feared that the most troubled and talented rock star of his generation would go the way of Jim Morrison and Jimi Hendrix. "Now he's gone and joined that stupid club," she told the Associated Press. "I told him not to join that stupid club."

Cobain didn't overdose like Morrison and Hendrix, of course. But the singer's self-destructive streak seems to have been bound up inextricably with drugs. In March, while in Rome, Cobain overdosed on painkillers and champagne. Nirvana's spokespeople insisted that it was an accident, portraying Cobain and his wife, Courtney Love, as stable, happy parents whose drug days were behind them. But the truth about Cobain's last months was far messier than we'd been led to believe. On March 18, Cobain reportedly locked himself in a room of his spacious Seattle home and threatened to kill himself; Love is said to have called the police, who arrived on the scene and seized medication and firearms. On April 2, the police were summoned once more—this time by O'Connor, who told them her son was missing. The rumor mill has it that Cobain and Love's marriage was on the rocks; that his friends performed an "intervention," and that while Love was promoting a new album by her band, Hole, Cobain was fleeing a rehab clinic in Los Angeles. According to the AP, O'Connor's missing person's report read, in part, "Cobain ran away from [a] California facility and flew back to Seattle. He also bought a shotgun and may be suicidal." All these dark machinations will make for an uneasy legacy—precisely the sort of legacy he didn't want. "I don't want my daughter to grow up and someday be hassled by kids at school," he once said of Frances Bean Cobain, now 19 months. "I don't want people telling her that her parents were junkies."

Which raises a question: what will they tell Frances Bean? Where her father's career is concerned, at least, the answer is reassuring. They'll tell her Cobain and his band hated the slick, MTV-driven rock establishment so much they took it over. They'll tell her that with the album, Nevermind, Nirvana replaced the prefab sentiments of pop with hard, unreconstituted emotions. That they got rich and went to No. 1. That they were responsible for other bands betting rich and going to No. 1: Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Alice in Chains. That Cobain never took his band as seriously as everyone else did—that he once wrote, "I'm the first to admit that we're the '90s version of Cheap Trick." But that despite his corrosive guitar playing, he wrote gorgeous, airtight melodies. That he took the Sex Pistols' battle cry "Never Mind the Bollocks," mixed it with some twenty-something rage and disillusion, and came out with this lyric: "Oh, well, whatever, never mind." And, finally, that he reminded his peers they were not alone, though all the evidence suggests that he was.

Cobain was born just outside the desultory logging town of Aberdeen, Washington, in February 1967. (Yes, he was 27, as was Morrison, Hendrix and Joplin). The singer hated being the crown prince of Generation X, but the fury of Nirvana's music spoke to his generation because they'd grown up more or less the same way. Which is to say: grunge is what happens when children of divorce get their hands on guitars. Cobain's mother was a housewife; his father, Don Cobain, was a mechanic at the Chevron station in town. They divorced when the singer was 8.

Drugs and punk: Cobain always had a fragile constitution (he was subject to bronchitis, as well as the recurrent stomach pains he claimed drove him to a heroin addiction). The image one gets is that of a frail kid batted between warring parents. "[The divorce] just destroyed his life," Wendy O'Connor tells Michael Azerrad in the Nirvana biography, Come As You Are. "He changed completely. I think he was ashamed. And he became very inward—he just held everything [in]. . . . I think he's still suffering." As a teen, Cobain dabbled in drugs and punk rock, and dropped out of school. His father persuaded him to pawn his guitar and take an entrance exam for the navy. But Cobain soon returned for the guitar. "To them, I was wasting my life," he told the Los Angeles Times. "To me, I was fighting for it." Cobain didn't speak to his father for eight years. When Nirvana went to the top of the charts, Don Cobain began keeping a scrapbook. "Everything I know about Kurt," he told Azerrad, "I've read in newspapers and magazines."

The more famous Nirvana became, the more Cobain wanted none of it. The group, whose first album, 1989's Bleach, was recorded for $606.17, and released on the independent label Sub Pop, was meant to be a latter-day punk band. It was supposed to be nasty and defiant and unpopular. But something went wrong: Nirvana's major-label debut, Nevermind, sold almost 10 million copies worldwide. On the stunning single "Smells Like Teen Spirit," Cobain howled over a sludgy guitar riff, "I feel stupid and contagious/Here we are now, entertain us." This was the sound of psychic damage, and an entire generation recognized it.

Nirvana—with their stringy hair, plaid work shirts and torn jeans—appealed to a mass of young fans who were tired of false idols like Madonna and Michael Jackson, and who'd never had a dangerous rock-and-roll hero to call their own. Unfortunately, the band also appealed to the sort of people Cobain had always hated: poseurs and bandwagoneers, not to mention record-company execs and fashion designers who fell over themselves cashing in on the new sights and sounds. Cobain, who'd grown up as an angry outsider, tried to shake his celebrity. "I have a request for our fans," he fumed in the linear notes to the album Incesticide. "If any of you in any way hate homosexuals, people of different color, or women, please do this one favor for us—leave us the f--k alone! . . . Last year, a girl was raped by two wastes of sperm and eggs while singing . . . our song 'Polly.' I have had a hard time carrying on knowing there are plankton like that in our audience."

By 1992, it became clear that Cobain's personal life was as tangled and troubling as his music. The singer married Love in Waikiki—the bride wore a moth-eaten dress once owned by actress Frances Farmer—and the couple embarked on a self-destructive pas de deux widely referred to as a '90s version of Sid and Nancy. As Cobain put it, "I was going off with Courtney and we were scoring drugs and we were f--king up against a wall outside and stuff . . . and causing scenes just to do it. It was fun to be with someone who would stand up all of a sudden and smash a glass on the table." In September '92, Vanity Fair reported that Love had used heroin while she was pregnant with Frances Bean. She and Cobain denied the story (the baby is healthy). But authorities were reportedly concerned enough to force them to surrender custody of Frances to Love's sister, Jamie, for a month, during which time the couple was, in Cobain's words, "totally suicidal."

By last week the world knew Cobain had a self-destructive streak, that he'd done heroin and that he'd flailed violently against his unwanted celebrity—but the world had been assured those days were over. Nirvana recently postponed its European concert dates and opted out of this summer's Lollapalooza tour. Still, spokesmen maintained that Cobain simply needed time to recuperate from the overdose in Rome. They offered a tempting picture: Cobain the tormented rebel reborn as a doting, drug-free father. Even Dr. Osvaldo Galletta, of Rome's American Hospital, says he believed the overdose was an accident: "The last image I have of him, which in light of the tragedy now seems pathetic, is of a young man playing with the little girl. He did not seem like a young man who wanted to end it. I had hope for him. Some of the people that visited him were a little strange, but he seemed to be a mild sort, not at all violent. His wife also behaved quite normally. She left a thank-you note."

It'd be nice if we, too, could come away with that image of Cobain and his daughter. And, in truth, those who knew the singer say there was a real fragility buried beneath the noise of his music and his life. Still, there are a lot of other images vying for our attention just now. Among them is the image of Courtney Love and Frances Bean Cobain, who are said to have arrived at their home in Seattle, via limo, late Friday. Again: what will people tell Frances? Ed Rosenblatt, Geffen Records president, says, "The world has lost a great artist and we've lost a great friend. It leaves a huge void in our hearts." That is certainly true. If only someone had heard the alarms ringing at the rambling, gray-shingled home near the lake. Long before there was a void in our hearts, there was a void in Kurt Cobain's.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.