I walked into Dr. Joseph A. Rudick's Manhattan offices almost entirely unaware of what Lasik eye surgery was, save for the countless rave reviews I heard from friends and family. "It's totally painless," I remember being told. "You'll have brand new eyes overnight!"

All I knew was that I had one more strip of daily contacts to go through, a broken pair of glasses and another one missing somewhere in New York City. I vowed to myself I wasn't going to buy another box of contacts—sticking something in my eye was my least favorite part of every single day, and I typically forgot to take them out virtually every night before falling asleep. And each week, I heard of another friend or coworker having lasik, or the PRK laser procedure, another form of corrective eye vision surgery, then glowing about how incredible life is from that point on.

Even Rudick spoke to Lasik's near-stainless reputation as one of the most advanced, life-changing, even utopian of procedures ever since the first surgery was performed in America in 1991. It's not like anyone was lying, either: one month after having Lasik eye surgery, I can attest to its incredible outcomes and boost to quality-of-life.

But I do wish someone, anyone, warned me of what the first 24 hours after having lasers shot in your eyes feels like.

After being reviewed and determined a perfect candidate for Lasik, I signed off on some forms noting the potential risks and complications that may occur after having laser eye surgery. The possible side effects read just like one of those commercials for a new prescription drug that ends with a one-minute voiceover narrating symptoms like heart failure, kidney rupturing and death, as a woman jogs with her golden retriever through a beautiful green field. Dry eye syndrome. Debilitating visual symptoms. Loss of vision.

Basically, every thing you wouldn't want to ever happen to your eyes in some unfortunate worst-case scenario is possible when going under the laser.

The FDA warns against "eye centers that advertise, '20/20 vision or your money back' or 'package deals' on its Lasik information site, noting quite poignantly "there are never any guarantees in medicine."

There also are sites like LasikComplications.com, which purports there to be a link between the surgery and blindness, corneal transplants and even suicide after having the operation done.

But Rudick's office was highly rated citywide, and I felt that I was in some of the best hands performing this surgery in the nation.

My own father had Lasik eye surgery more than a decade ago, when the laser machines were less advanced (albeit still highly successful). So I signed off and prepared to have surgery in a week. I let the surgeon and his receptionists know I wouldn't have anyone available to pick me up as it was in the middle of the week and my apartment was at least an hour away, but was reassured they'd order me an Uber on my way home from the procedure.

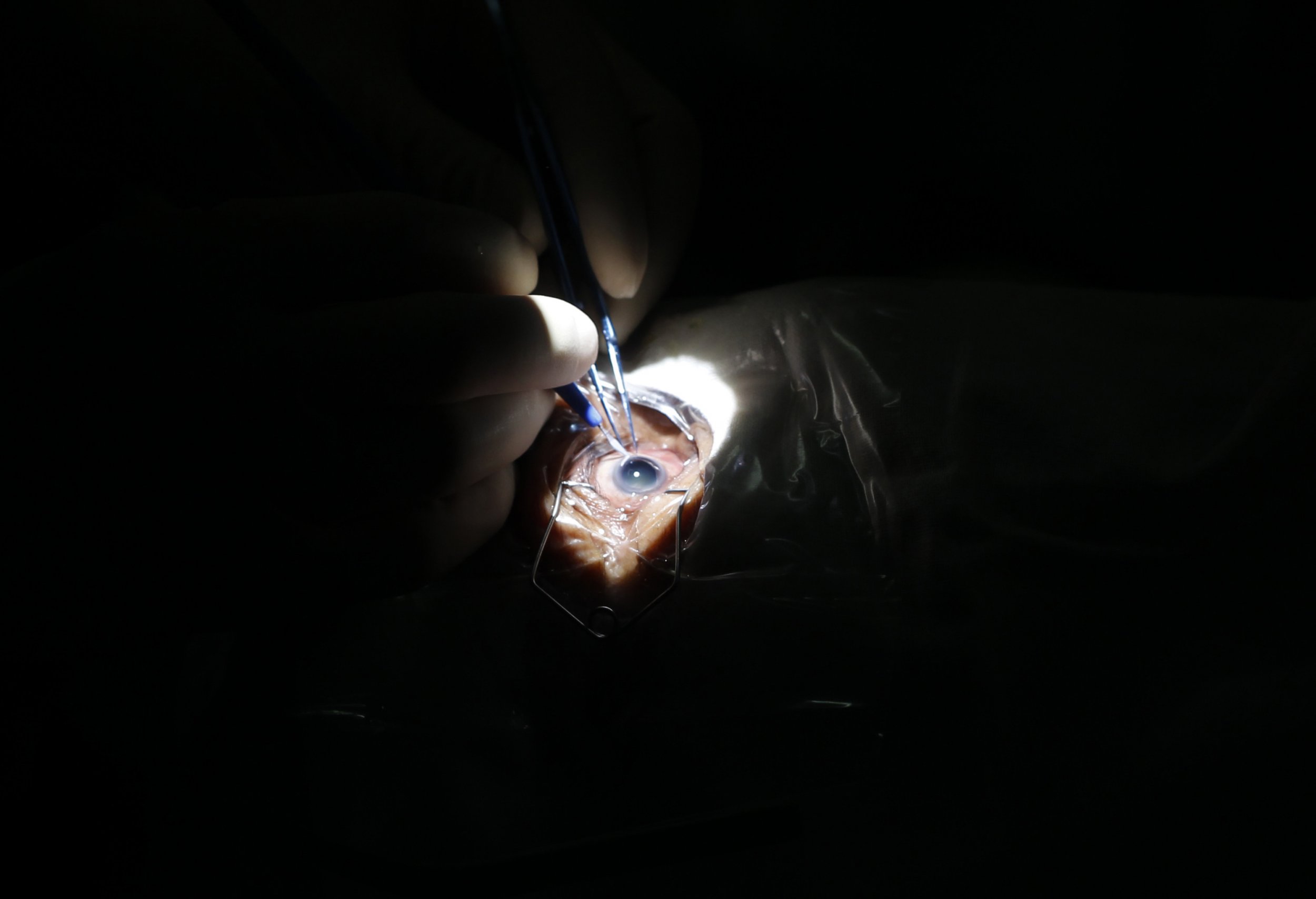

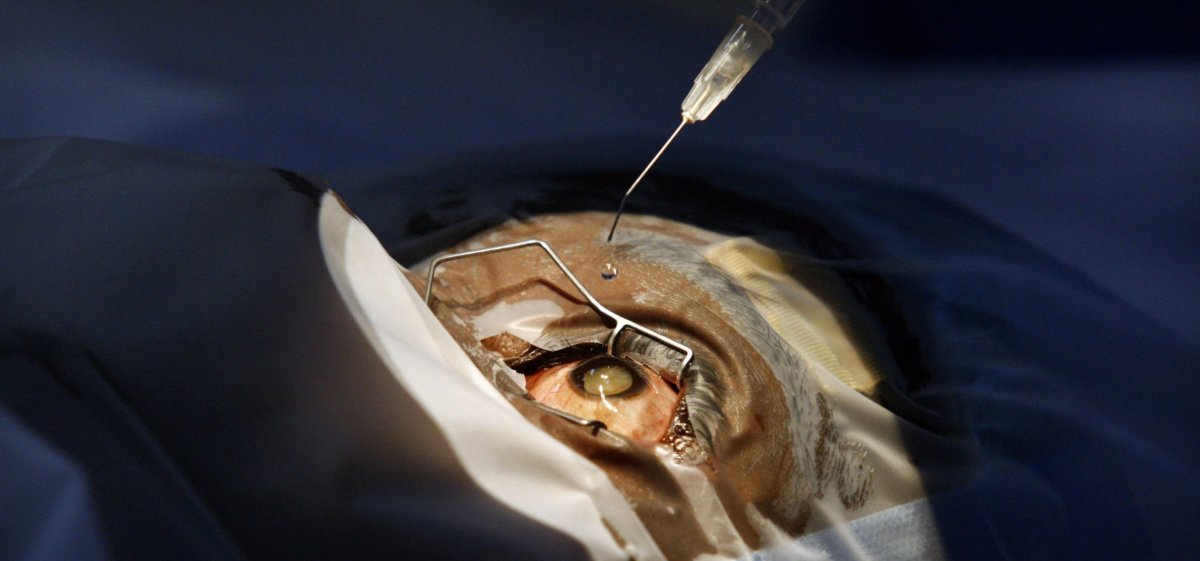

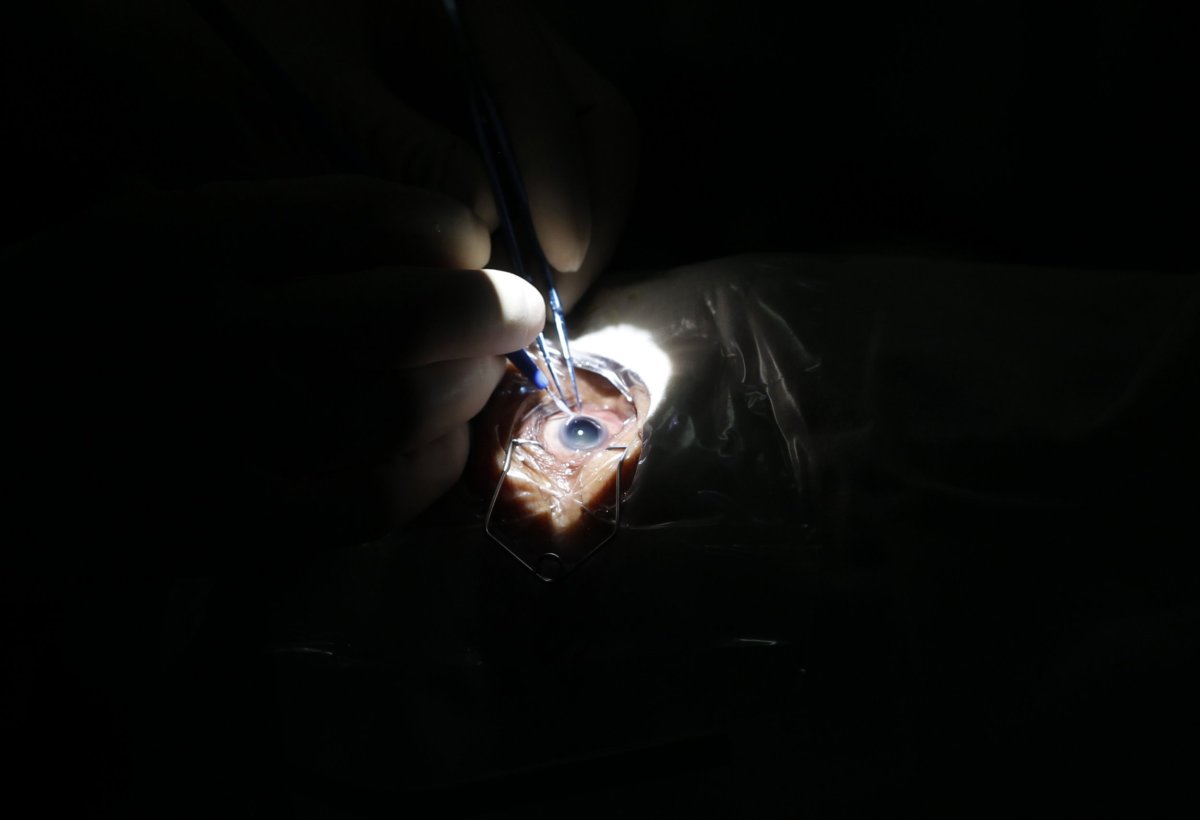

I won't go into too much detail about the actual surgery, largely because it only lasted a total of three minutes or so. Each eye took about thirty seconds, after both receive a healthy dose of numbing solution before going under. I was given a blanket to wrap myself in as my face and eye were strapped in and held with restraints, and a teddy bear whose name the nurse said was "See-more."

After having the surgery, I immediately was able to sit up and see the entire room around me. See-more was colorful and clear laying on my lap. The time on the clock above the wooden door on the other side of the room read 2:47 with crystal clear clarity. The surgeon then doused my eyes in multiple solutions, and I was given goggles and sunglasses to protect my eyes from the lights. "Your vision is going to get pretty blurry over the next few hours," Rudick told me. "Go home and try to go straight to sleep."

My sight was rapidly dissipating as I was escorted into the hallway, exiting the surgeon's office and being left alone in the general lobby. I hadn't reminded anyone for an Uber, and felt uncomfortable going back in and relying on someone to help me get back home to Brooklyn.

Out of my entire Lasik experience, going alone was my biggest mistake.

By the time I was standing in the lobby, I could barely look at the screen on my phone. The words were too bright, and all of the colors were beginning to run together. I managed to order an Uber and pushed my phone into my pocket, waiting for it to buzz.

My first Uber finally arrived 10 minutes later, with the driver frantically calling to say he was outside of my address. I walked out of the building, immediately feeling the burst of light stab through my sunglasses and into my wounded eyes. My eyes felt scratchy and dry as I squinted around in search of a black SUV that was supposed to be for me.

I spoke with the driver on the phone for a good five minutes before learning he actually was nowhere near my dropped location, and would have to make three different turns around two blocks to get to where I was standing. He then decided to hang up on me and cancel the trip. By this point, my eyes were dry, and my vision was so blurred, I felt completely helpless.

Fortunately, a second Uber driver proved to be the ultimate hero, picking me up moments later and taking me to a bodega before going home to buy me snacks that he chose to pay for. I begged him to at least take my cash into the store, but he left the car running and came back with Doritos, Diet Coke and Twizzlers. My eyes were shut throughout the entire drive home, and the driver helped me into my apartment before heading off.

That first night after having Lasik surgery was one of the most uncomfortable experiences I've ever had in my life. It felt as though my eyelids were glued to my corneas, as bugs crawled between the skin, scratching every inch over and over again. If I opened them, I was met with immediate pain. I couldn't sleep, or even move much, out of fear I was going to break or smash into something.

I did not fully open my eyes until the next morning at about 9 a.m., after slowly taking off the goggles I had been wearing since immediately after the surgery. My eyes were bloodshot and teary as I looked at myself in the mirror, but I noticed the immediate accuracy in my vision the second I saw my face. I could see the red capillaries in my eyes that had burst from the pressure during the procedure, and the lashes on my eyelids.

I went back to my surgeon that morning to learn the operation was a success. In fact, it went even better than expected: I was found to have an eyesight of 20/15, better than perfect eye vision. Rudick informed me the redness was perfectly normal and would disappear in a few days. It did.

All in all, Lasik is an incredible surgery with the enormous potential to give someone back their eyesight for a lifetime overnight. But it's no miracle: the operation requires a patient's understanding there is a small risk involved with major implications. Despite what one may be told before the procedure, there certainly is a great deal of discomfort in the proceeding hours and days, though every person's recovery is different. And unlike other options, Lasik is virtually never covered by insurance, and costs a much prettier penny upfront than glasses or contacts.

Still, there's something incredible about being given the ability to see the world without any help in 24 hours. "It's like pregnancy," my mother said. "The result is so beautiful, it almost makes you forget about the trauma."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Chris Riotta is a reporter from New York and is a Master's candidate in Journalism at Columbia University. He has ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.