On a fall day in 1988, at the height of the AIDS epidemic, hundreds of activists descended on the Food and Drug Administration headquarters in Rockville, Maryland. Blocking the doors and walkways, they chanted, "Hey, hey, FDA, how many people have you killed today?"

The death toll in America had reached nearly 62,000 people, and the protesters were demanding that drugs be developed and approved faster. "A friend launched me onto the overhang of the front door of the building," says Peter Staley, who hung a huge banner with the now-iconic slogan, "Silence = death."

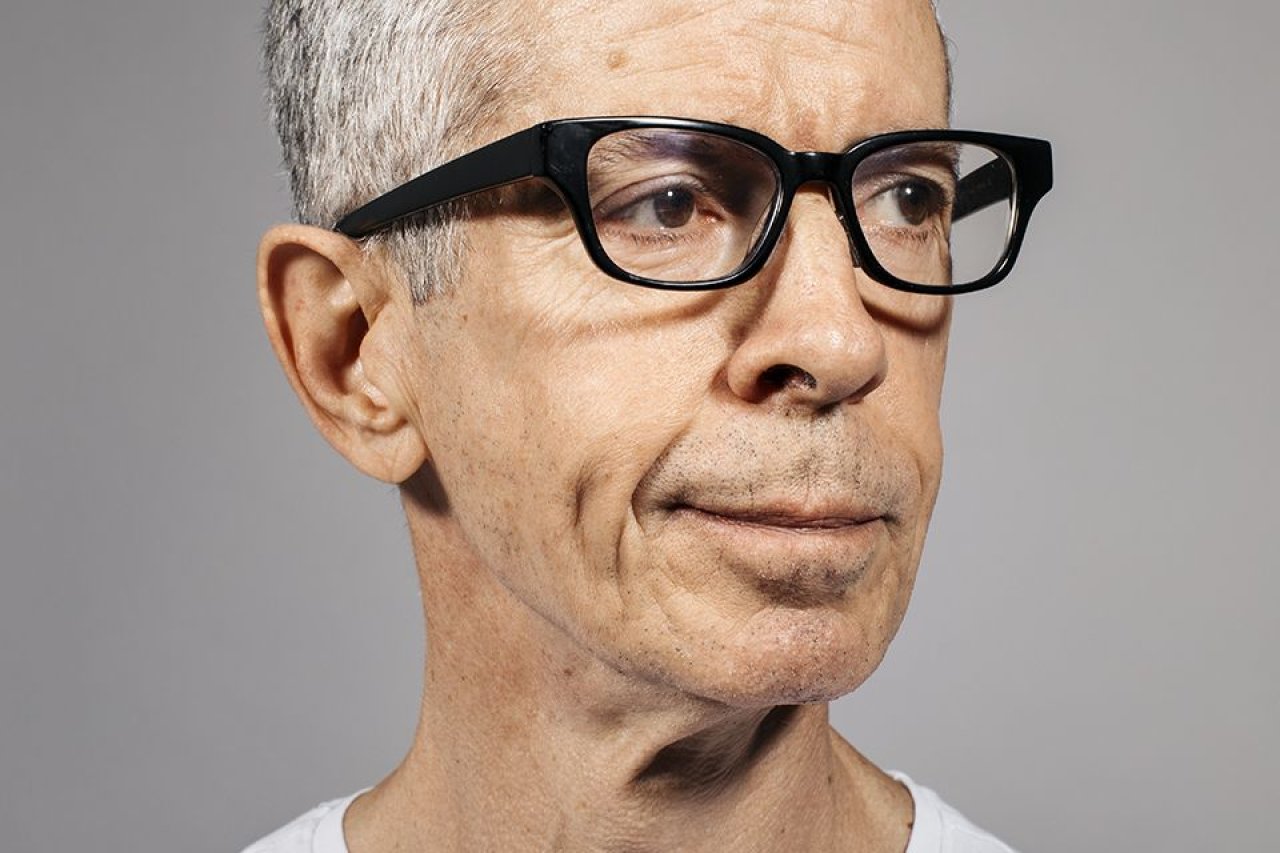

As a member of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), Staley was among those leading the protest. He was 27 at the time and had been diagnosed with AIDS three years earlier. Staley was certain the disease would kill him too.

That day at the FDA was the beginning of changing the hearts and minds of the American people, he says now. "We gave them a gigantic guilt trip, and that led to federal dollars for AIDS research and the tripling of the National Institutes of Health research budget in three years."

In the three decades since, Staley, 57, has helped save millions of lives (including his own), with ACT UP and then TAG (the Treatment Action Group), his nonprofit focused on accelerating treatment research, founded in 1991. Once again, Staley knew how to make headlines: At a TAG launch event, he draped a giant condom over the house of North Carolina Republican Senator Jesse Helms, an outspoken opponent of AIDS research. The massive sheath read, "A condom to stop unsafe politics—Helms is deadlier than a virus." (Years later, Staley revealed that the event was sponsored by entertainment mogul David Geffen.)

Long an icon of the LGBT community, Staley became a national star with the release of How to Survive a Plague, David France's 2012 Oscar-nominated documentary, in which he is featured prominently. A moving portrait of the power of protest, Plague shows how ACT UP members like Staley and their relentless pressure on government agencies transformed the way drugs were researched in the U.S. and sped up the rollout of AIDS treatments.

Now, Staley is writing his memoir (due in 2019 from Chicago Review Press), not only to document his "wild ride" in the AIDS movement but also because he fears that democracy, liberalism and pluralism are under threat in a way they haven't been in decades. Social activism can create remarkable change when the world feels like a "very scary place," he says. "My activism has always been based on optimism, and I truly believe that activism means overcoming pessimism. That's what I hope comes out of this memoir."

Consider that ACT UP accomplished radical change without the benefit of social media. Indeed, it is often used as a blueprint to effectively change policy through protest. "There are many, many lessons for today's activists [from that era], regardless of what they're fighting for," says Staley. "I'm a loyal and angry member of today's resistance."

ACT UP was founded in March 1987, and AIDS activism obviously has a very different face today. Those in their 20s are savvier politically and better organized, and thanks to medications, such as the preventive drug pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), the disease is preventable, and does not equal death. Lobbying lawmakers to ensure treatments are widely accessible has replaced headline-worthy stunts. And protesting has become less effective than regional campaigns, like the one that persuaded Mayor Bill de Blasio to make New York the first U.S. city to pilot needle exchanges, preventing the spread of HIV and other contagious diseases among drug users.

But when ACT UP began, there was no viable treatment and the mysterious diseasewas killing young, predominantly gay men and intravenous drug users in slow and horrifying ways. The challenge was to make the country care about a group rejected and feared by much of America. That required gaining the public's attention with often sensational methods.

As a former J.P. Morgan bond trader (his brother is the CEO of Barclays bank), Staley was an unlikely radical, but he was a longtime troublemaker. "I was a bit of a prankster in high school," he says. He joined J.P. Morgan after college, and two years later received his diagnosis. "When people are handed a death sentence, there are two paths they can take," he says. "They can curl up and wait for the inevitable, or they can fight for extra months or years. That's all we did." He and his ACT UP comrades lived as though they might die tomorrow: "We didn't know if we'd see the fruits of our activism."

Staley was on his way to work when he was handed a flyer for the first demonstration. For a "crazy" year, he was a Wall Street bond trader by day, radical activist at night. "It took a collapse in my immune system to force my decision to go full-time activist," says Staley.

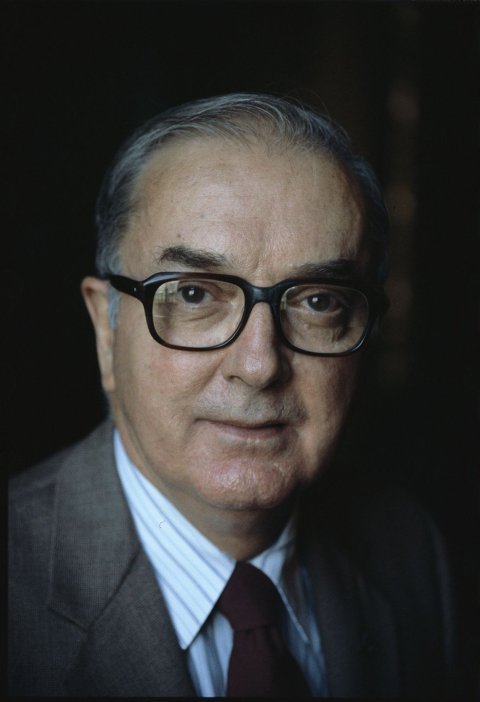

By 1991, AIDS was killing more young men than almost any other disease in the U.S., and Staley was learning that protest is a long game. Helms supported the politicians who defined AIDS as a "gay plague"—punishment for what they regarded as immoral behavior. Those with the disease were therefore unworthy of having tax dollars spent on researching life-saving drugs. "We have got to call a spade a spade and a perverted human being a perverted human being," Helms told the Senate in 1988. He was backing a bill denying federal funding to AIDS programs and argued that such programs "promote, encourage or condone homosexual activities."

As one of the most despised groups in the country, "we turned our grief and anger into action," says Staley. Yet the death toll kept climbing; campaigners were winning the battle but losing the war.

By 1997, over 6.4 million people had died worldwide. It wasn't until 1996 (a decade after ACT UP's FDA protest) that scientists came up with the cocktail of drugs that would prevent HIV from replicating and developing into AIDS. With that discovery, "the death rate in U.S. and Europe dropped by 80 percent in one year," says Staley, "which was an extraordinary medical advance."

Staley's moments in How to Survive a Plague are memorable, particularly footage of his brilliant evisceration of Pat Buchanan, Ronald Reagan's White House director of communications, during a televised debate. It led to an invitation to appear in the 2013 Oscar-winning film Dallas Buyers Club. That film is about AIDS patient Ron Woodroof (played by Matthew McConaughey), who smuggled unapproved drugs into the U.S. and distributed them to fellow patients, including a trans woman played by Jared Leto. Staley is rumored to have salvaged the initial script, which he admits was troubling (he is given "very special thanks" in the credits). When the movie was released, critics complained of the inaccurate depiction of Woodroof's life, as well as the casting of a cisgender, straight man to play a trans woman.

Staley, who found the final film underwhelming, considers it a victory of sorts. "A major Hollywood AIDS movie is pretty rare," he says, "so when one gets made and wins Oscars, it's a plus for the cause."

Staley is still an activist. He and his partner and their dog divide their time between rural Pennsylvania and an apartment in New York City's West Village, not far from where ACT UP first recruited him. There's still plenty to be done: He and his TAG colleagues continue to push for increased testing; they help the HIV-positive find treatment and make sure PrEP is available for the most at-risk communities, including gay people, African-American men and trans people—all those disproportionately affected because of a prejudiced system, says Staley. "We could end AIDS today if we made the effort, and that's the huge change from the early years."

He sees groups like Black Lives Matter as the descendants of ACT UP, but he has mixed feelings about the internet and social media. "They should be viewed as very powerful tools but not as your solo platform," he says. "There is nothing that replaces getting a group of like minds in a room and brainstorming how to change the world. If you try to replace that by staying at home on the computer, you'll never get anything done."

The pro-gun control teenagers of the March for Our Lives campaign—who combine the reach of social media with traditional boots-on-the-ground activism—have filled him with real hope. "I think they are extraordinary," he says. "They are showing wisdom beyond their years."

This is "a terribly frightening time" to be alive, he says, with legitimate fears about the rise of nationalism and even fascism, both here and around the world. But Staley, ever the optimist, is convinced that the just shall overcome. "Social movements are always two steps forward, one step back," he says. "We are in an inevitable path towards greater equality."

This article has been updated to correct that the FDA released a cocktail of drugs to prevent HIV from developing into AIDS in 1996, not 1998, and to remove the suggestion that PrEP contains protease inhibitors. A reference to Peter Staley acting as a consultant for the Dallas Buyers Club has also been changed to say that he was thanked in the credits of the film.