When regulators at the Federal Trade Commission take steps within the coming weeks to strengthen the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998, they could well be acting with Vicki Turner in mind.

Along with raising her three kids, ages 16, 13, and 7, and working a job with handicapped children and adults, the 43-year-old resident of Fullerton, Calif., also spends a big part of her life monitoring her oldest kids' online activities: steering them away from inappropriate content, preventing them from uploading photos of themselves onto commercial sites that invite them to do so, and occasionally making them unfriend a person on Facebook whom Turner considers undesirable. When told about Mark Zuckerberg's declared ambition to open Facebook to children under the age of 13, she sighs. "He just cares about what will profit him," she says.

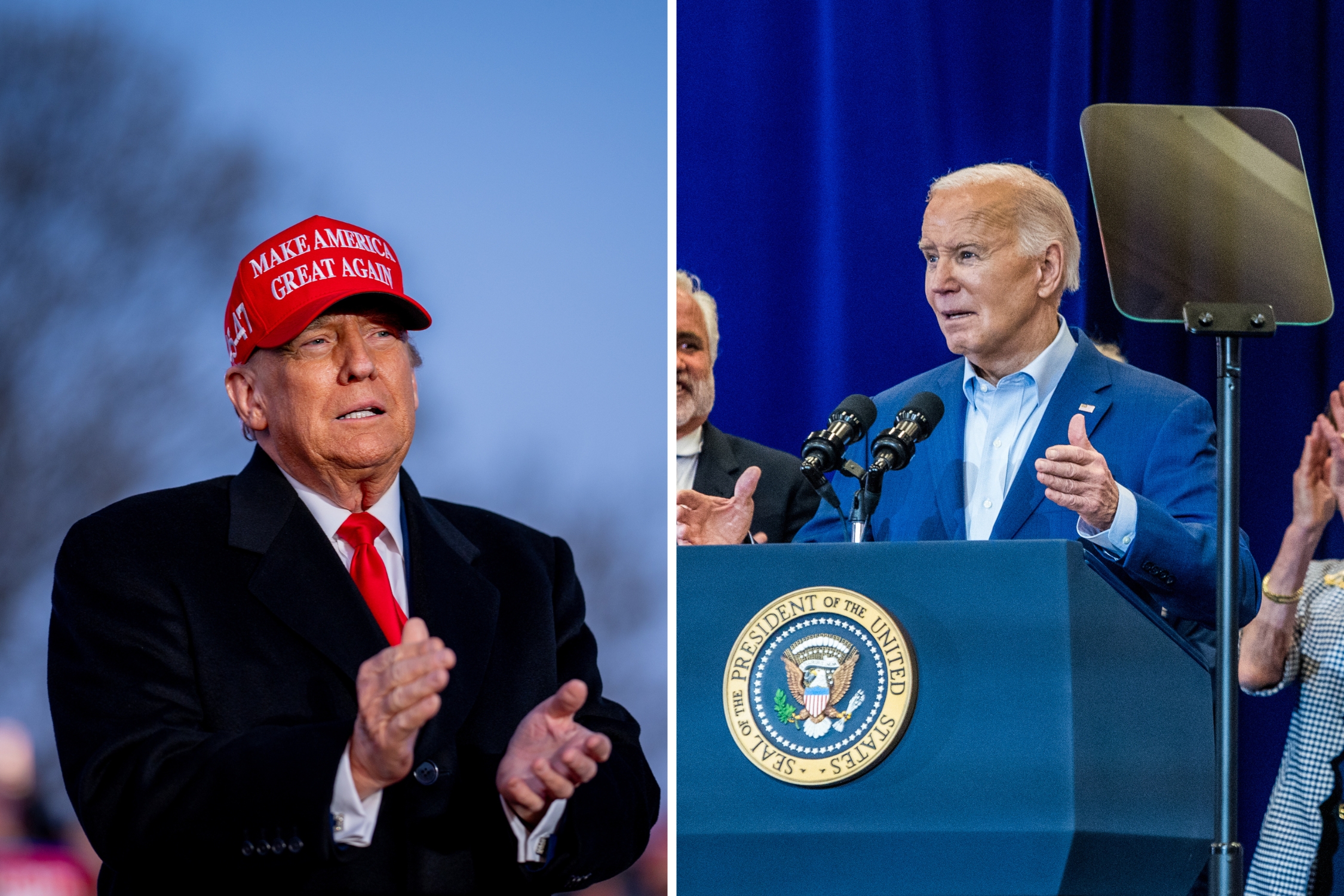

In fact, Facebook, which hit a billion users last week, has sent a 20-page letter to the FTC imploring the agency to reconsider its planned revision of the 1998 act, which would prohibit the collection of information from children online, a lucrative practice that the social-networking behemoth clearly would not like to give up. Yet the FTC, though sharply criticized by an advertising industry unhappy with the proposed changes, says that current laws meant to shield children on the Internet have fallen way behind advancing technology. Entities, ranging from large corporations to obscure apps to roving data collectors, gather up children's personal information, photographs, and even their physical location. Antiquated laws requiring parental permission for such things are easily circumvented by cookies that document children's online movements the way birds devoured the crumbs of bread that Hansel and Gretel hoped would guide them back home.

For besieged parents, the FTC's proposed revisions cannot arrive a moment too soon. But welcome as those changes will be, they will have little effect on the Internet's social environment, which in many ways has made being a modern American parent more complex than ever before. "It used to be the proverbial question: 'It's 10 o'clock, do you know where your children are?'" says Jamie Wasserman, a child therapist with a practice in Manhattan. "Now your kid can be sitting a few feet away from you in the living room with a laptop, being damaged."

By "damage," Wasserman doesn't mean only the danger of meeting a predator on the Internet. She is also referring to what seems to be an almost infinite spectrum of online harm. A child could be bullied or harshly excluded from an instantly formed clique. At the same time, the pressure to be constantly posting, tweeting, and updating one's status threatens to obstruct the development of what used to be called, in unwired times, a child's "inner resources." With all the frenzied social networking on sites like Facebook, our kids are often forced to be social before they have become socialized.

Even for the most gregarious children, the Web's constant reminder of majority opinion makes them fearful of trying to say or do anything that doesn't please the crowd. Yet appealing to the Web's masses also offers them the temptation to say things they would never ordinarily have uttered in public—things that can come back to haunt them later in life.

I look at my own children, a 6-year-old boy and a 2-year-old girl, and I wonder not just what the world has in store for them, but also how they will be able to find the world. When I was 5, people used a typewriter and talked on a landline. When I was 35, people were still conversing on old-fashioned phones. Between the time my son and my daughter were born, texting overtook both cellphones and emailing, desktop computers became obsolete, Twitter was born, the iPod passed through several generations, and both the Kindle and the iPad were invented.

The process of maturing is a movement from a rich yet defensive inner space to the outer reality of pleasure postponement, setback, and perseverance. But the Internet offers one recessive chamber after another of inwardness; it is a place where distraction and immediate gratification become cognitive tools in themselves. The main barrier between parent and child, which looms gigantic in adolescence, is the stubborn insularity of a child's world. These days that insularity has its own enabling techniques, skills, and idiom. What used to be quaintly called the generation gap is now adorned with the corporate logos of Apple, Google, and Facebook.

This is why few people seem sympathetic to Facebook's desire, publicly announced over the summer, to sign up children under 13, especially parents like Turner, who are fighting against escalating odds to keep up with ever-accelerating technology that they barely understand but which their children have mastered to the point of jadedness. Thomas Hughey, a school counselor at Lancaster High School in Lancaster, Wis., for 20 years, routinely encounters students "so connected to all the digital stimulation that it ruins their day. They're so used to instant stimulation that"—like overburdened business executives—"they don't have downtime."

"For my kids," says Miriam Ancis, an artist in Brooklyn, N.Y., who has three teenage children, "the Internet is the air they breathe, how they function in the world." Professor Howard Gardner, a developmental psychologist at Harvard who believes that intuition, creativity, and interpersonal skills matter as much as the formal intelligence measured in standardized tests and whose theory of "multiple intelligences" has changed the way children are taught, says it's often the case that today's youth "don't know whether they're online or not." That is a sea change in human relations, not to mention in the parent-child dynamic.

Recent studies showing that kids spend at least four hours a day on social and recreational media, distracted and disengaged from the world and each other, have caused yet another ripple of alarm. And increasingly, parents fear that their children's "electronic fingerprints" will hinder their path through life.

"Kids are losing jobs because of things they posted," says Hughey. For Sherry Turkle, a social psychologist who has been studying the effects of computers on personality for nearly 30 years, the Internet's breach of privacy is a public tragedy. "We were absolutely not paying attention," she said. "We taught our children not to care about privacy. A whole generation was let down."

The concern with privacy is precisely what the FTC is now moving to address. Yet throughout the country, parents, educators, and mental-health experts are voicing their concern over not just the commercial invasion of privacy, or Facebook's domination of American life, but also the conventions of digital culture itself. "Our kids are being socialized by each other at warp speed," says Wasserman. "They're never off social duty." For the most hurt, withdrawn children, Wasserman says it's like "Columbine on crack."

Dr. John Huxsahl, co-chairman of the Division of Child Psychiatry and Psychology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., says the Internet "allows you instant access to what other people desire more than to what you desire." Confor-mity becomes an end in itself—what Hughey calls "a new category of peer pressure." Even Turkle's MIT students are not immune. "They leave their phones on the seminar table" and wait for the little red light to blink, she says, "just to see who wants them."

Of course, it is the transformation of chil-dren into desirable objects that alarms parents the most when Zuckerberg speaks of opening Facebook to the very young. "The Internet has created greater access to children," said Cynthia Carreiro, a supervisory special agent in the FBI. Ironically, says Carreiro, it's the very young children whose self-protective mechanisms are sharpest when they see the actual face of a predator. "Young kids are really grossed out," she says. But on the Internet there are no physical danger signs standing between the seductive machinations of a monster and an innocent child.

Recent reports that a new flirting app, called Skout, resulted in three separate cases of children being raped by older men have driven home the dangers confronting minors when they go on the Web. After the rapes, Skout banned minors from the site, but they've since readmitted them, with new safeguards. Carreiro says that "parents have to educate themselves on how to protect their kids online." At the same time, she is concerned about the rapid pace of changing technology. "It's becoming more difficult for parents to block access," she says.

That is, if they want to block access. According to a Consumer Reports article published last May, 7.5 million kids 12 and younger are on Facebook. Some of those kids' parents helped their children create a fake birth date to get them access to the site. The fear of being disconnected can be even stronger for parents than for their sons and daughters. Gardner tells the story of parents who get around some summer camps' prohibition against electronic devices by packing in with their children's supplies teddy bears that have a cellphone or iPod sewn, prison-break style, into their tummies.

Then there are the parents who themselves become like children in the hands of the Internet. Several students have come to Hughey seeking help after walking in on a parent watching porn on the Web. They felt "shocked, betrayed, confused," he said. Other students complained to him that their parents were so wrapped up in the Internet they didn't come to ball games or spend time with their kids.

On several occasions, Hughey said, a divorced parent, after connecting with someone online, piled the kids into the car and drove off to start a new life with a person neither the parent nor the children had ever met. In one case, a single mother hauled her family to Texas from Wisconsin, only to get a "bad vibe" once she saw her online lover in the flesh. Returning to the hotel, she took to her laptop to check up on him and discovered that he had a criminal background. Then it was back to Wisconsin with her scared and confused children.

While parents such as these struggle with Internet addiction and disorientation, many children are actually becoming weary of their digital rounds. "Some kids complain about keeping up with the pace of the Internet," says Huxsahl. "It's a time of life when people are so vulnerable, so insecure, so cliquey," he says. The jarring effect of being excluded online, or being "defriended" creates in some children a defensive aversion to the medium that is hurting them.

"Kids will print out postings of harmful things and bring them to me," says Thomas Hughey. A public-school teacher in Metuchen, N.J., says that her high-school students themselves "express concern about what they're exposed to" on the Web, especially porn sites. And, she says, "they get sick of a lot of the gossipy drama" they encounter on social-networking sites like Facebook. Sometimes, she wearily confided, "I just want to tell my students, 'Get off the Internet and go watch TV.'"

C.J. Sprowls, a 22-year-old college student in La Habra, Calif., is not one of the disenchanted. He says that he has been online since he was 8 years old. He now spends between six and 11 hours a day on the Internet. His closest friends, he tells me, are people he first encountered online and has never seen, though he has talked to all of them on the phone.

Sprowls says that he has never felt threatened or uncomfortable on the Web. He dismisses the notion that the Internet is a powerful distraction, pointing to the fact that he can carry on "three conversations on three different subjects" simultane-ously. I confess to him that I can't imagine this has not badly affected his attention span. "Not at all," he says. "I can read a book and watch TV at the same time."

As for the rising evidence that the Internet is having negative effects on everything from kids' ability to learn to their safety and their privacy to their development as persons, Sprowls concedes the Internet's shortcomings, but he doesn't think all the blame should fall on the Web. "Parents are failing to raise their children," he says. "They should teach them better."

Blaming parents for the Internet's ills hints at a disappointed expectation that parents will fulfill their traditional role as guardians and protectors. In some respects, Sprowls' surprising accusation is a plea for parents to take firmer control. And no doubt the pendulum will swing between a more regulated Internet and a more untrammeled one for some time to come. When, in defiance of advertisers, corporations, and online businesses, the FTC finally overhauls anachronistic laws governing commercial conduct online, that will be one important step toward a new equilibrium between individuals and the economic forces that rule the Web.

In the meantime many parents will continue to approach the Internet in a spirit of poignant improvisation. While Miriam Ancis refuses to employ any of the proliferating new technologies able to monitor her teenage children's online lives, she subtly deploys her own surgeon general–type warning, counseling her kids to put a pillow between themselves and their laptop. "It gives off radiation," she tells them, hoping—as parents have always hoped—that her children will discover for themselves what she really means.

Lee Siegel is the author of four books and the e-book Harvard Is Burning.

Policing the Digital Playground:

February:

Communications Decency Act (CDA) establishes regulations to protect minors from pornography on the Web. Parts of it would later be found unconstitutional for violating the First Amendment.

October:

The Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) of 1998 seeks to regulate the collection of personal information from children.

April:

COPPA goes into effect.

February:

Mark Zuckerberg launches "Thefacebook" for Harvard students.

September:

Facebook launches a version for high-school students.

September:

Facebook opens to anyone 13 and older.

June:

Facebook announces plan to develop controls allowing children under 13 to use the social-media site.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.