It was 49 years ago—April 30, 1975—that Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese. I remember, as a kid, watching the last U.S. personnel and thousands of at-risk South Vietnamese being airlifted out of the country to waiting ships by helicopter—the largest such evacuation in history, and quite a stunning sight to behold on black-and-white TV.

It was an ignoble defeat after a decade's effort in which 58,220 Americans were killed—equivalent to about 20 Sept. 11s and almost 10 times the U.S. fatalities in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars that followed. How could it have happened? And what might we have learned?

It happened, or at least lasted so long, because of an idee fixe—an obsessively rigid notion that should probably be reexamined but which the victim, as if by a witch's hex, cannot escape. The concept was popularized by the 19th century French composer Hector Berlioz in his "Symphonie fantastique," in which the protagonist's recurring musical theme represents an obsessive thought or idea that haunts him throughout the piece.

The idee fixe can infect policymakers as well—and in the case of Vietnam, it was the "Domino Theory." This was a geopolitical concept popularized during the Cold War era, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, which sought to resolve the First Indochina War between France and the communist Viet Minh forces led by Ho Chi Minh. The theory posited that rises and falls in democracy were contagious, and that if one country in a region came under the influence of communism, then neighboring lands would follow suit, like a row of falling dominoes.

The Domino Theory was used by the Kennedy and Johnson administrations as the philosophical undergirding of the massive commitment to propping up the corrupt, authoritarian, and unpopular regime in South Vietnam. The fear was that if South Vietnam fell to communism, then neighboring countries in Southeast Asia would also succumb, destabilizing the region and providing the Soviet Union and China with strategic advantage.

In fact, the USSR and Communist China were rivals, and Vietnam was highly suspicious of Beijing because of its long history of resisting Chinese occupation and interference (preceding, of course, the French colonization of the modern era).

One indication that things were more complicated should have been that Ho Chi Minh, the leader of North Vietnam, sought U.S. support in the early years of Vietnam's struggle for independence, fighting both the Japanese and the French. Ho hoped that as a champion of democracy and self-determination, the United States would support Vietnam's independence.

In 1945, he drafted the Vietnamese Declaration of Independence, which was modeled after the U.S. Declaration of Independence and appealed to American ideals. He was also a believer that communism was the best means to achieve his nationalist goals. Either way he was rebuffed—at a rather high cost in retrospect.

That calculation might have occurred to the Americans on April 29, 1975, as North Vietnamese forces encircled the city and approached its outskirts. As chaos and panic gripped the city, the U.S. began a large-scale evacuation effort known as Operation Frequent Wind, airlifting American citizens, embassy staff, and South Vietnamese allies to safety aboard helicopters and other aircraft.

Despite the fears associated with the Domino Theory, the spread of communism did not extend dramatically beyond Laos and Cambodia for a while. Neither Cambodia nor Vietnam today can be called communist states—nor can they be called democratic, admittedly.

In her book "On Lying and Politics," the historian and philosopher Hannah Arendt uses this debacle as her defining example of how falsehoods buttress fantastical worldviews, as key individuals within political systems may become desensitized to lying, prizing loyalty to an idee fixe over adherence to the truth. She notes that U.S. intelligence consistently told the generals and politicians that Vietnamese support for the Vietcong was indigenous and that the Domino Theory was wrong, such that the U.S. could pull out and "all of Southeast Asia was remain exactly as it is for at least another generation."

"The divergence between the facts ... and the premises, theories and hypotheses according to which decisions were finally made is total," Arendt writes, devastatingly.

Considering that, perhaps the second-biggest lesson of Vietnam is that for a leader like John F. Kennedy, a reputation can survive even the greatest of foreign policy fiascos with a few domestic achievements, some decent public relations, a dynastic political context, and a rather friendly press (to be fair, the unpopularity of the war was a factor in President Johnson's decision not to run in 1968).

As regards the first lesson, I see little evidence that we have lost our vulnerability to the charismatically delivered, organically sown, or otherwise well-timed idee fixe.

Exhibit A might be trickle-down economics, also known as supply-side economics or Reaganomics, which assumed in the 1980s that by cutting taxes on the wealthy and reducing regulations on businesses, the benefits of economic growth would "trickle down" to everyone else, leading to increased investment, job creation, and prosperity for all. Instead, the most provable result has been stupendous levels of inequality and a widespread disdain for all economics.

Exhibit B might be the belief in the 1990s that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction, which was a central justification for the U.S. invasion in 2003. The failure to uncover the alleged WMDs undermined the credibility of the Bush administration and led to accusations of intelligence manipulations, misinformation, and worse—a classic idee fixe that led to another costly and controversial military intervention.

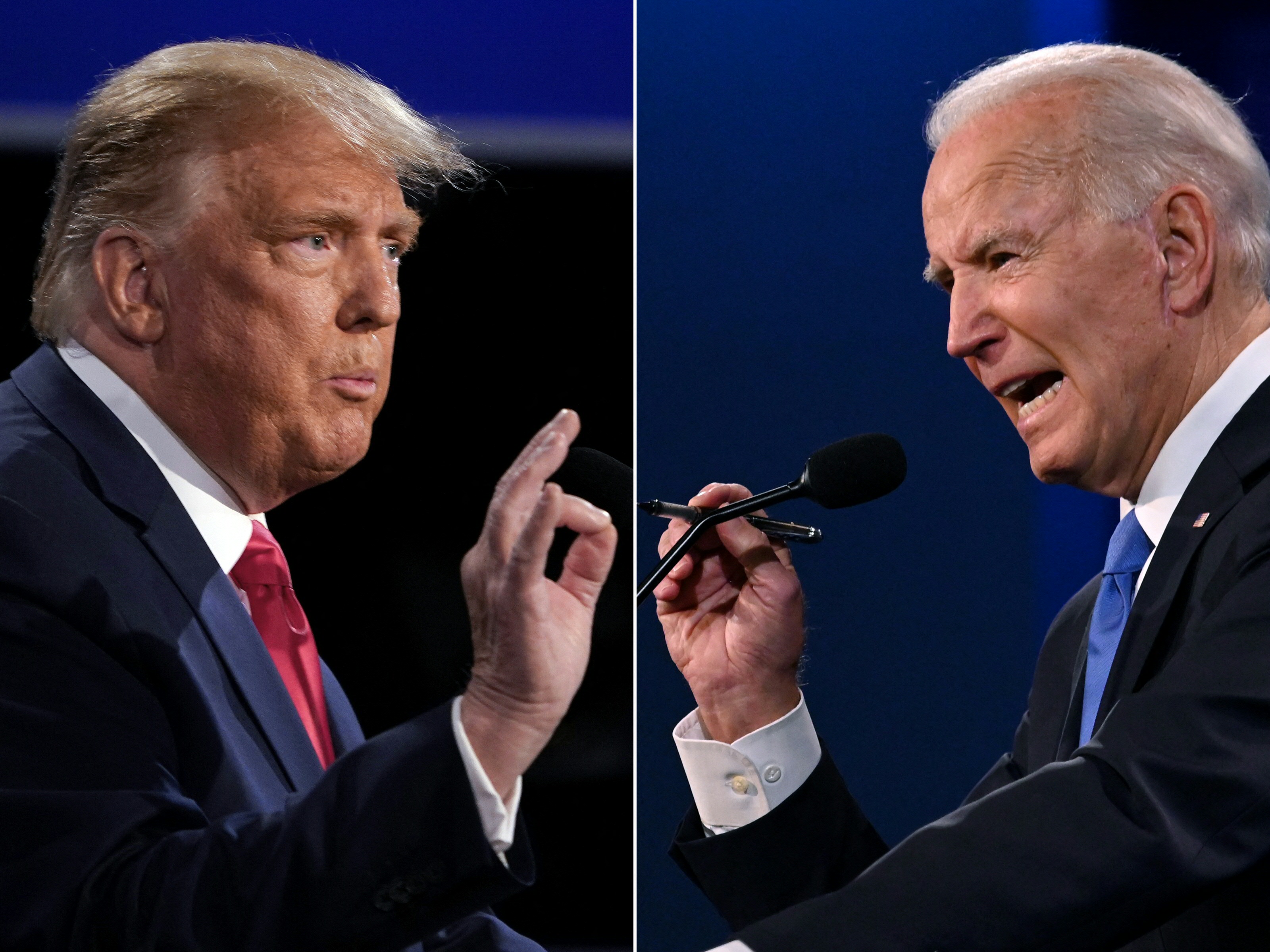

As Exhibit C I offer globalization, an ideologically driven concept in which the international elites had by the 2000s convinced everyone that treating the world as a single economy without regard for dislocations in any one region would maximize global wealth. It can just as easily be seen as prioritizing the interests of multinational corporations and wealthy nations at the expense of workers, communities, and the environment. Mainly, it transferred so much of manufacturing out of the West that we now have dependence on non-democratic countries for our supply chains, and so much working-class anger that we could end up once more with Donald Trump as president.

The 2010s brought us the progressive tsunami, at least in the West, whose array of narratives swept like wildfire through U.S. campuses, non-conservative media, and HR departments. These seem to view everything through the prism or race and gender identity, and a war on once-privileged groups by means of a "decolonization" imperative. Resisters beware: this idee fixe has some bite, as billionaire author JK Rowling has found out.

Perhaps the idee fixe du jour is the idea that the march of technology will always lead to progress and cannot be resisted unless one is a "Luddite," in which case one should be mocked in merciless fashion.

Sure, technological progress generally does benefit us—longer lifespans, greater wealth, instant access to information, eased communication. But it can also create tremendous devastation—not just dynamite and nuclear weapons but an unreasonable degree of inequality and labor dislocation. I'd argue that recognizing the limitations and potential drawbacks of tech advancement is essential for ensuring it serves the broader interests of society, and this might require regulated, taxation and at times perhaps suppression.

You don't need to take it from me—take it from ChatGPT, which wrote much of that last paragraph. When these bots take over, no helicopter airlift will save you.

Dan Perry is the former Cairo-based Middle East editor and London-based Europe/Africa editor of the Associated Press. Follow him at danperry.substack.com.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.