Mars is the next great human frontier: a vast, arid desert lying millions of miles from Earth. Elon Musk thinks it will be our species' next home, and space agencies around the world agree. They're scrambling to discover all they can about the dry and freezing planet with billion-dollar missions.

Orbiters and rovers are probing the planet's surface, its atmosphere and even its climate. NASA's InSight lander—which launched May 5—will study the planet's interior. The European Space Agency's ExoMars Mission, on the other hand, will look for life.

The Red Planet's barren exterior might be hiding evidence of past and present life. A thick layer of permafrost could be sheltering tiny, organic molecules. The ExoMars rover will drill where this layer is thought to exist. If it's hiding even the most basic signs of life, the rover wants to find them.

The ExoMars mission—which sent an orbiter and a demonstrator lander into space in 2016—is a collaboration between the ESA, Roscosmos, the UK Space Agency, and aerospace companies including Airbus and Thales Alenia Space. Newsweek visited the Airbus facility in Stevenage, U.K., to learn more.

New Town, New Industries

Stevenage—an industrialized town in the heart of eastern England—is the country's first postwar "New Town." Neat, orderly suburbs straddle a siloed industrial park. Deep inside the Airbus complex, engineers tinker with swatches of honeycombed aluminum and tanks of rocket fuel.

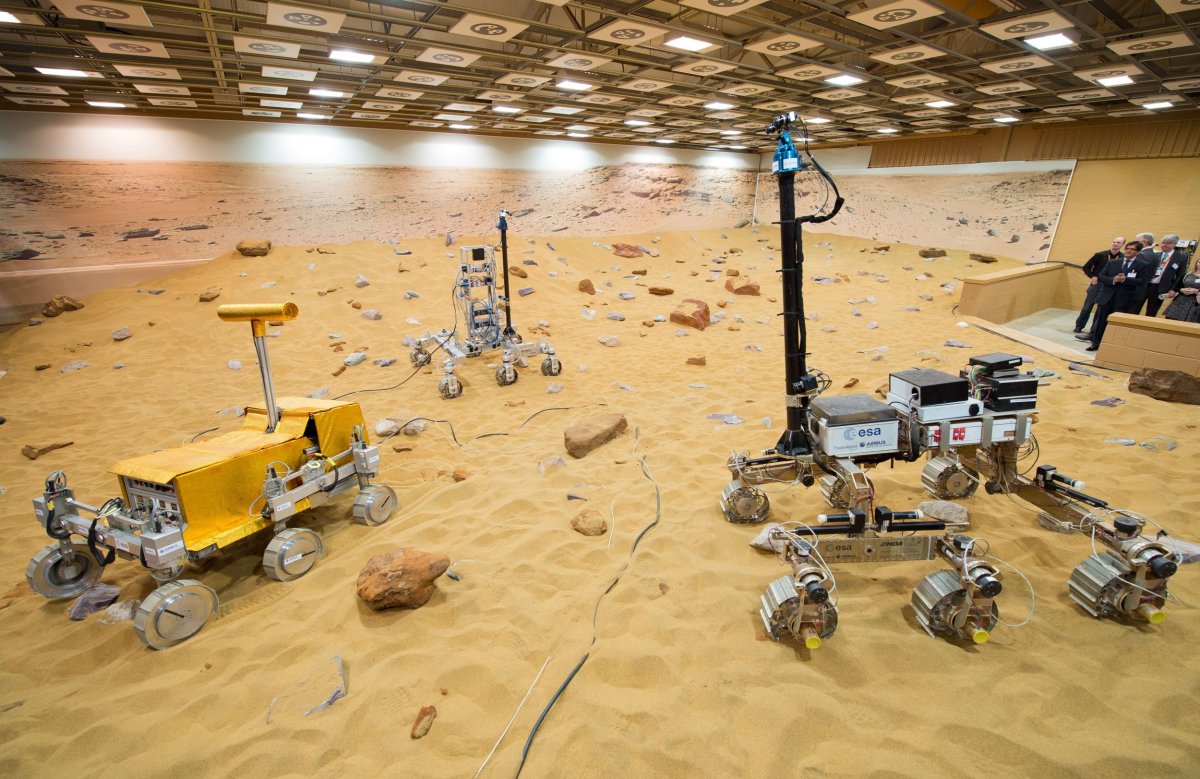

Glass corridors glitter with satellite models and shards of the world's purest quartz. Door after door eventually leads to the most exotic sight of all: Mars Yard—a 100 by 40 ft Red Planet mock-up.

Read more: NASA wants to get a helicopter to fly above Mars

An ExoMars Rover prototype clicks and whirs as it travels across baby dunes of arid, iron-speckled sand at a speed of almost an inch a second. High-tech dehumidifiers purge its home of moisture. The sand on Mars, after all, is dryer than that on our hottest beaches.

Rocks—from large pebbles to small boulders—pepper the almost-alien ground. The vehicle—which looks a lot like Wall-E, or Johnny 5, depending on your generation—tilts and rattles as it makes its way over a medium-sized rock. It looks like it's about to topple, but it conquers the rock with ease.

Two cameras peer down from a six-and-a-half-foot mast, which rises from the rover's carbon fiber belly. The "bathtub," as it's affectionately known, is stuffed with scientific instruments. A drill on the front of the vehicle will collect samples from more than 6 feet below the ground, which the rover will probe for water and signs of life. Scientists think these organic molecules, or "biomarkers," are "the very building blocks of life," Paul Meacham, lead systems engineer on the ExoMars Rover Vehicle Project, explained to Newsweek.

Six noisy wheels support the box of tools. Engineers had to create compressible metal wheels that mimic rubber tires. "[Rubber is] an organic material, and if we're looking for signs of life, we don't want to detect something that we've brought with us," Meacham explained. The team knitted together small strips of bendable steel to create a flexible wheel that can tackle inclines of up to 26 degrees.

Read more: NASA's future moon missions will help build "railroad" to Mars, says new chief

The rover's autonomous navigation system will help it steer clear of larger rocks. Its mast-mounted cameras act as eyes, giving it black-and-white 3D vision that can analyze the alien terrain. Technicians back on Earth will send the rover target locations, but it will calculate many of its own routes. The Trace Gas Orbiter already circling the planet will act as a communications satellite, beaming data from the rover back to Earth.

Dangerous Dust

The rover is set to probe Mars for a minimum of six months, but Meacham hopes the mission will last much longer. Martian dust will eventually suffocate the rover, collecting on its solar panels and blocking the sun's rays.

"That will probably be the thing that ends our mission one day," Meacham said, "when we're not able to generate enough power to keep the rover alive at night." Freezing temperatures will damage the battery and kill the vehicle.

That is of course, if it makes it to Mars in the first place.

A Treacherous Journey

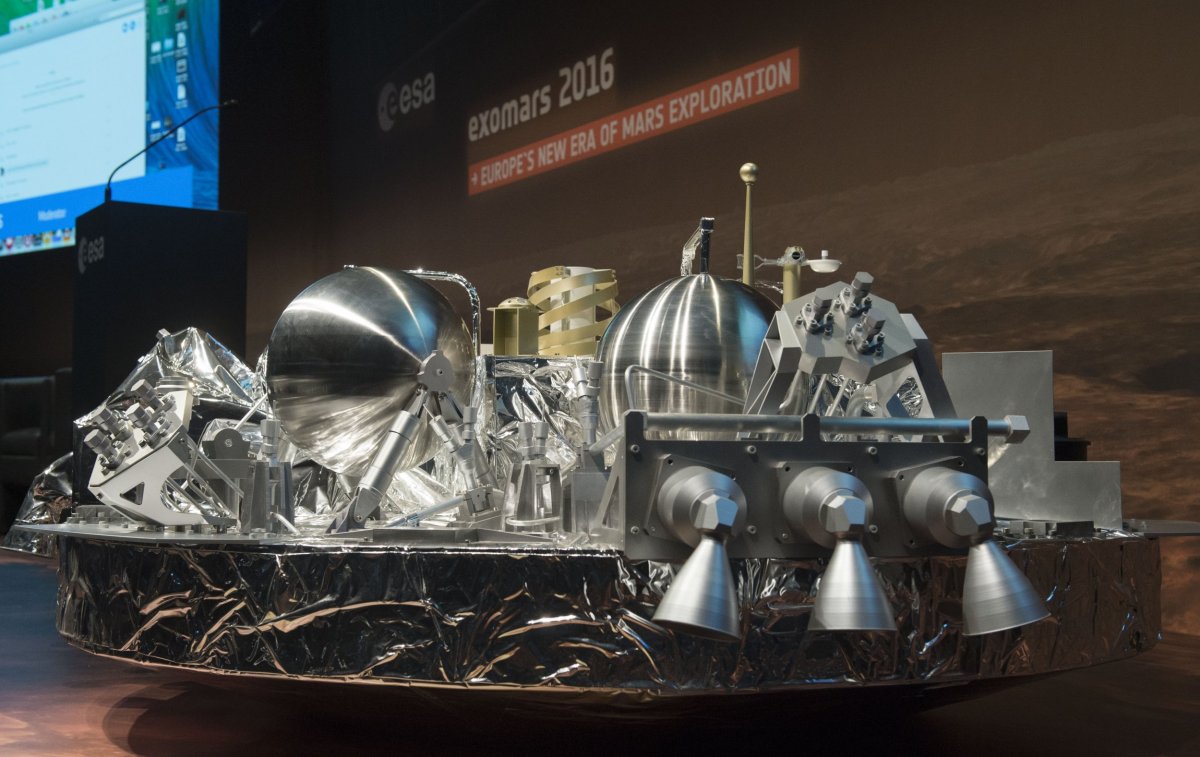

The Schiaparelli lander sent alongside the mission's orbiter crash-landed on the Red Planet back in 2016. About halfway down to the surface of Mars, the lander deployed its parachute. This made it swing back and forth like a pendulum, making a sensor think it had already landed. Schiaparelli fell to the surface, some 2-and-a-half miles down.

The craft was a technology demonstrator, so technicians were tracking its every move. "Because we had the data for that descent we know exactly why it happened," Meacham said. Equipped with the knowledge of what went wrong, ExoMars engineers should be able to prevent the same disaster, he said.

Life on Mars—Past, Present and Future

If any life is waiting to be found on Mars, Meacham thinks it will likely be bacteria. These hardy microorganisms can survive extreme conditions on Earth. How likely the rover is to actually find anything is harder to predict. "I like to think we will find something, because there's quite a lot of evidence that Mars was not unlike the Earth at different points in its history," Meacham added.

Even if it doesn't strike gold, the rover will help scientists and engineers move closer to that all-important goal: a human mission to Mars. Rovers answer vital questions about the planet's terrain, and their results will shape human exploration in the future.

"A lot of the scientific results from these missions will then actually direct where a human mission might go and who we might send on a mission like that. Will we send a biologist or a geologist? Or both?" Meacham said. "These missions are really, really important in leading us towards that human mission."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Katherine Hignett is a reporter based in London. She currently covers current affairs, health and science. Prior to joining Newsweek ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.