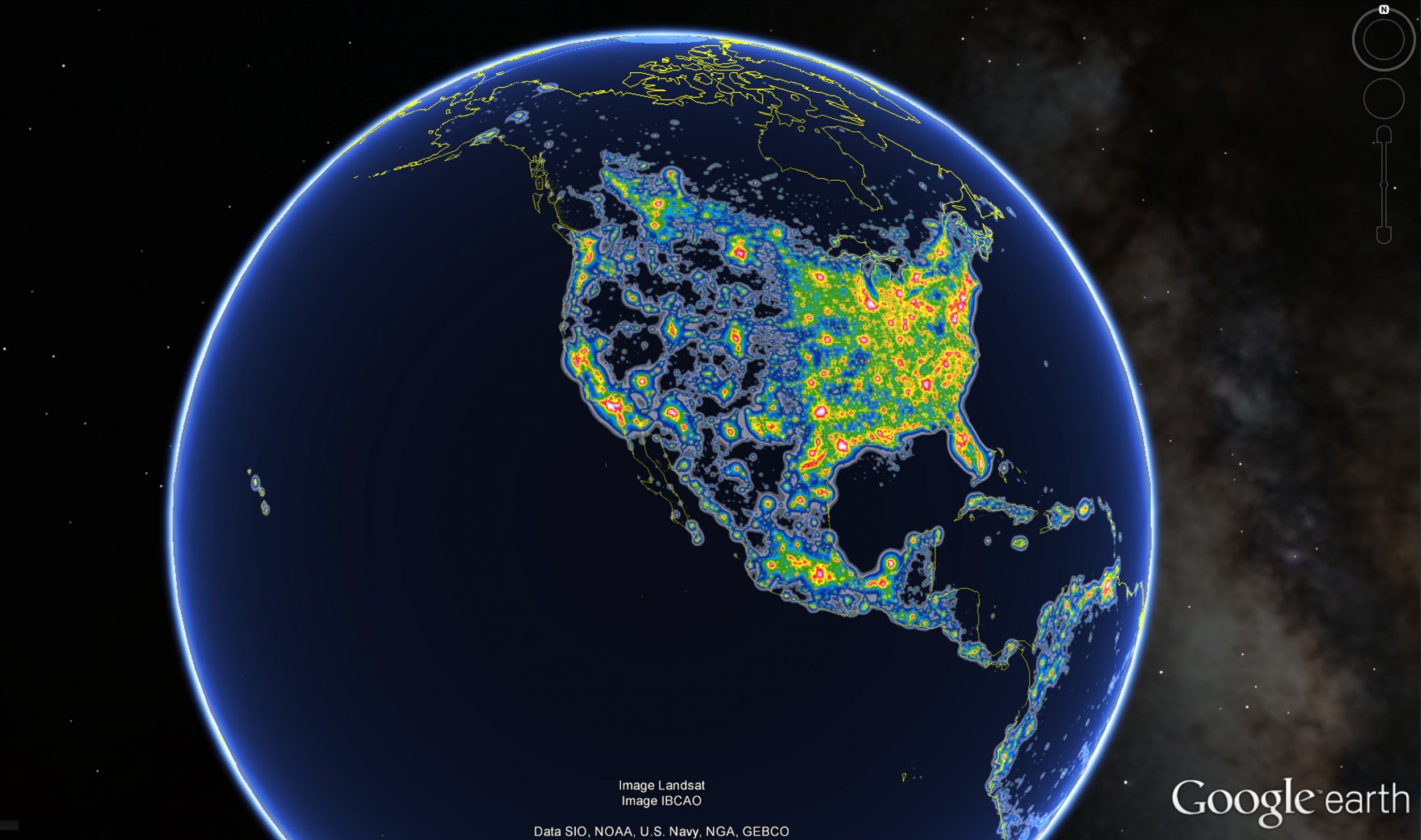

Since lightbulbs began lighting up streets and homes at the start of the 20th century, stars in the night sky has been an increasingly rare sight in cities and suburbs. Now, after over a century of artificial luminescence, researchers say that one-third of the human population can no longer see the Milky Way, with most of the industrialized world living under a dome of light population.

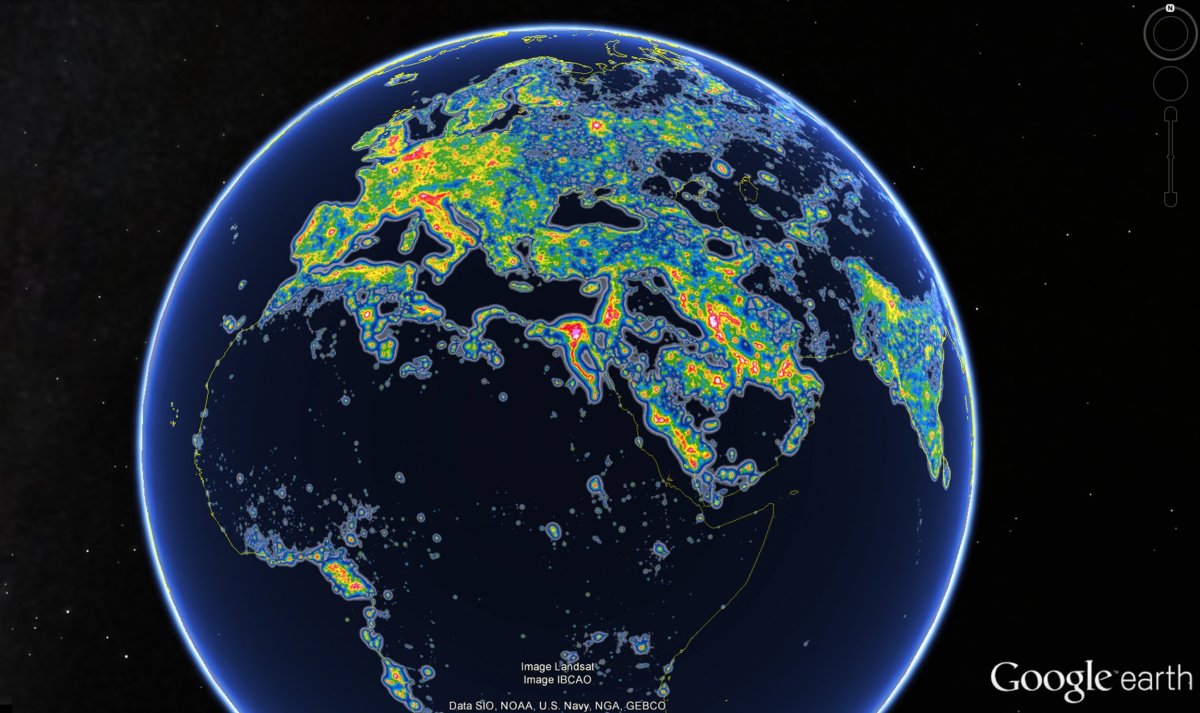

Researchers from Italy, Germany, the United States and Israel published a paper on Friday documenting a global census of light pollution. Most of Western Europe's skies are polluted by "skyglow"—the brightness of the night sky due to air pollution—with only pockets of rural Scotland, Scandinavia, Austria and Spain remaining pristine. The United States east of the Mississippi River is similarly polluted in one connected tapestry of bright lights.

The Milky Way, which is our galaxy viewed as a long band of stars, is now hidden from 60 percent of Europeans and 80 percent of Americans, unless they venture into national parks unaffected by light pollution.

Among the G-20 developed countries in the world, residents in India and Germany are most likely to be able to see the Milky Way from their homes. Despite being the largest country in Western Europe, Germany uses significantly less light than its neighbors, thanks to light-conscious policies in towns and cities and a cultural conservatism that restricts light pollution, according to Christopher Kyba, one of the authors of the study, who works in Berlin.

"In Germany, the Autobahn doesn't have lights on at night. The parks in Berlin are sometimes not lit because people believe parks should be like natural reserves," Kyba tells Newsweek. "American cities use per person three to five times more light than German cities. In Belgium and the Netherlands, which are right next door, highways and streets are more brightly lit."

Countries with a high population density recorded high levels of light pollution. Due to its small geographic size and a high population, South Korea finished last among developed countries in being able to see the Milky Way and first in light pollution level. Heavily urbanized places like Singapore were even worse. There, the entire population "lives under skies so bright that the eye cannot fully dark-adapt to night vision," according to the study.

The global study was a joint effort by both an international group of scientists and volunteers. Kyba says he ran a crowdfunding campaign in Germany to buy cheap sky-quality meters to give to elementary school students in Berlin to record light at night. As scientists in the field generally focused on areas yet unaffected by light pollution, volunteers recorded urban light pollution levels en masse, providing comprehensive global data.

"We got data in all six inhabited continents," Kyba says. "We thought they were complementary to each other."

To help curb light pollution, Kyba recommends that cities turn to warm-colored, low-temperature LED lights, which run on lower temperatures and are dimmer. While warm-colored LED lights were inefficient in saving energy costs in the past, recent LED technology has put them on a par with bright-white LED lights in terms of energy efficiency.

Like their German counterparts, few American cities have taken action against light pollution in recent years. The city of Davis, California, decided to replace its high color temperature LED lights with low-temperature alternatives in 2014 because residents complained the streets were too bright at night.

Bright artificial lights in public spaces like pedestrian roads or parks negatively affect plants, animals and humans living nearby. Nocturnal animals' and reptiles' hormonal levels and mating behaviors are affected by artificial lights, according to other scientific research. Brightly lit cities can also disrupt bird migration routes, according to Kyba.

But to protect wildlife from light pollution, Kyba says, governments and people across the world need a new way of thinking about lights. "During the 20th century, the use of electric lights just increased continuously," he says. "My dream is that cities will take this more seriously and use efficient lights. Well lit and brightly lit are not the same anymore."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Seung Lee is a San Francisco-based staff writer at Newsweek, who focuses on consumer technology. He has previously worked at the ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.