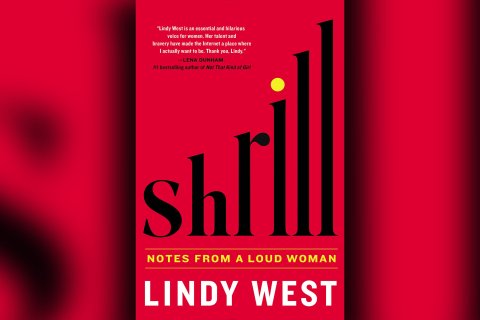

Lindy West isn't going to whisper about size, periods or abortion. She's not going to shut up about sexism, online harassment or why comedians should stop with the rape jokes either. She describes herself as "fat" and called her new memoir Shrill to point out the "really blatant and egregious double standard" of the gendered word—no one calls men "shrill"—and explain why that label is usually just an excuse to discredit women's ideas. "Once I've pointed out the hypocrisy of the word shrill," she tells Newsweek, "then if you use it, you're being a dickhead."

In print and in person, West is witty and relatable. The girl who wrote that she once peed her pants in grade school because she was too afraid to ask the teacher if she could go to the bathroom has become a self-professed loud woman who makes keen, vulgar and hilarious observations about society and her life. As I read the first chapters of Shrill: Notes From a Loud Woman, I started keeping a mental list of all the offbeat terms she used for the female anatomy. There was "shame canyon," "magic triangle" and "vagin-UUUUUUUGGGHHHHHHHH." She called tampons "vagina plugs" and described them as "like a severed toe made out of cotton."

The memoir, published in May, "is largely about my journey from quiet to loud and figuring out how to be loud and big in all of these different areas," West says, speaking on a recent trip to New York City a few days after the book came out. Having completed the previous day's marathon of media interviews, a reading, and recordings for This American Life and the 2 Dope Queens podcast, she was getting ready to fly to St. Louis to kick off a book tour that will stop in cities all over the U.S. and U.K. The process, she says, was "obviously [about] learning how to feel OK about being big physically, but also about being big in my presence and trying to make a big impact on the world."

West started writing in 2005 at famed Seattle alt-weekly The Stranger, where she worked her way up from intern to staff film critic and writer of the comedy column "Chuckletown, USA, Population: Jokes." She got a national platform as a staff writer at Jezebel—a Gawker Media–owned site with the tagline "Celebrity, Sex, Fashion for Women. Without Airbrushing"—and since leaving that site in 2014 has written for GQ, Cosmopolitan and The New York Times. Most recently, West has been a columnist for The Guardian, where she writes about current affairs, politics and culture, including her response this past September to the "Dear Fat People" video that went viral on YouTube.

"Indeed, it is 'hella brave' and 'new' to tell fat people to eat less and exercise more—much like the bravery of Braveheart, or the brave girl from Brave, or the weird old guy who used to come into my work when I was 17 and try to sell me pyramid scheme weight-loss pills that I'm 99% sure were tapeworm eggs mixed with Adderall," she wrote. "The bravery of thin people who exploit and abuse fat people for profit is truly unmatched."

For years, West has been a crusader against the issues that most affect women and other vulnerable groups—bullying, body shaming, slut shaming, racism and transphobia, to name a few. The fact that she does so all over the internet has helped her gather a large and supportive fan base (including nearly 70,000 Twitter followers). Shrill gives the details behind several of the most high-profile moments of her career, but it also touches on deeply personal experiences. It is "more vulnerable than what I usually write, even though I already get super personal."

In one chapter, she describes the first time she ever called herself fat to another person—via instant message with her boy-magnet roommate, during her sophomore year of college. "I will always be alone. I'm fat. I'm not stupid. I know how the world works," she recalls typing. "No one had ever sent me flowers, or asked me on a date, or written me a love letter," she writes years later. "No one had ever picked me. Literally no one. The cumulative result was worse than loneliness: I felt unnatural. Broken." Later, she tells readers about the man who became her husband, from the moment they stood as two friends backstage at a comedy show—where she became increasingly furious at a performer's lazily offensive herpes jokes and whispered to him about it, and he later told her that's when he began to realize she wasn't just funny, but "might be a really, really radically good person"—to the night he proposed.

She starts one chapter musing about the "decoy purch" strategy—adding random items like baby carrots or toilet paper to a shopping basket containing, say, a pregnancy test—and continues by describing frankly her relationship with her ex, who "made me feel lonely, and being alone with another person is much worse than being alone all by yourself." She talks, and writes, about her decision to get an abortion, despite people who would prefer women stay silent on the matter—people she describes as "zealous high school youth-groupers and repulsive, birth-obsessed pastors" who tell "vulnerable young women that all abortions are traumatic and all abortions are dangerous and all abortions are regretted and fetuses are babies and just pump these lies out into the water supply that serve no purpose except to strip women of their autonomy."

In the wake of efforts to defund Planned Parenthood last year, West helped launch the hashtag #ShoutYourAbortion, which was not meant to assign any positive connotations, she says, but to show "we're not obligated to be quiet.… Those of us who are privileged enough to live safe, stable lives where we're not going to be disowned by our families, and we're probably not going to be murdered for being open about abortion, have an obligation to do that for all of the women who can't."

West is especially proud of the time she got an apology from an internet troll (virtually unheard of on the wild web) who had set up a Twitter account in her father's name soon after he died of cancer. The troll wrote "embarrassed father of an idiot" on the account's bio and harassed West. She blocked him and then wrote about the experience in a biting story for Jezebel that caught her harasser's attention. As she recounts in the chapter "Slaying the Troll," the post pushed him to email an apology, delete the account and later agree to speak to West for a segment on This American Life. The show drew the attention of then–Twitter CEO Dick Costolo, who admitted that his company had failed to deal effectively with the kind of abuse West and others faced and vowed to fix it.

"Part of my work that's gotten bigger and bigger and more explicitly important to me is helping other people feel less alone," she says. "I get emails that say, 'Thank you, no one's ever told me that I had value before.' I mean, people don't tell fat people that they have value. Women are devalued. There are so many different systems telling people they're garbage in a million different ways." What she does is not on-the-ground activism—"I'm not sailing around the world performing abortions"—but she wants her writing to help make even just a few people with complex lives feel less like garbage.

And it's not just women she wants to relate to. "If a man wrote a memoir like this, it would just be a memoir. It would be a piece of literature—a book that anyone could pick up," West says. "Because it's about women's lived experiences, suddenly it's this froufrou, whiny, niche, shrill thing." The book tries to combat that reaction from every possible direction. The cover design, for example, is consciously un-girly, with a red, yellow, black and white color scheme rather than shades of pink or purple.

"My plan was to try to trick men into reading it," West says. "Women already know a lot of this stuff."