Modern humans settled on the African island of Madagascar, in the southwestern corner of the Indian Ocean, thousands of years later than commonly thought, according to a study published in the journal PLOS ONE.

Understanding the history of the island's colonization is key for tracing prehistoric human dispersal across the Indian Ocean, due to its location 310 miles east of Africa and around 3,700 miles away from Southeast Asia.

"Madagascar is the largest of the remote islands in the Indian Ocean and Malagasy [people] combine Southeast Asian and East African populations," Atholl Anderson, lead author of the study from the Australian National University, told Newsweek. "When it was colonized is therefore an index of human maritime capability and long-distance migration and trade across the ocean."

Despite the significance of its colonization, researchers have long been unable to agree on when human settlement of the island began. Some evidence, such as the discovery of stone tools and charcoal, indicates human occupation from around 1,500 years ago. On the other hand, research based on animal bone cut marks has suggested that the first settlers may have arrived more than 4,000 or even 10,000, years ago.

"Nearly all recent findings in archaeology, historical linguistics, paleoecological change and human genetics indicate late settlement of Madagascar, after about 600 A.D.," Anderson said. "The main stumbling block to acceptance of that age is repeated claims that some megafaunal bones dated up to 10,000 years ago exhibit butchery marks."

To shine a light on the discrepancies in the available evidence, Anderson and colleagues examined bones dated from between 1,900 and 1,100 years ago belonging to extinct megafauna on the island such as hippos, crocodiles, giant tortoises, giant lemurs and elephant birds.

"We undertook the largest ever study of bone damage on Madagascan material, including nearly 3,000 specimens—of which about 2,000 were from extinct megafauna—that we excavated from three sites under controlled conditions," Anderson said.

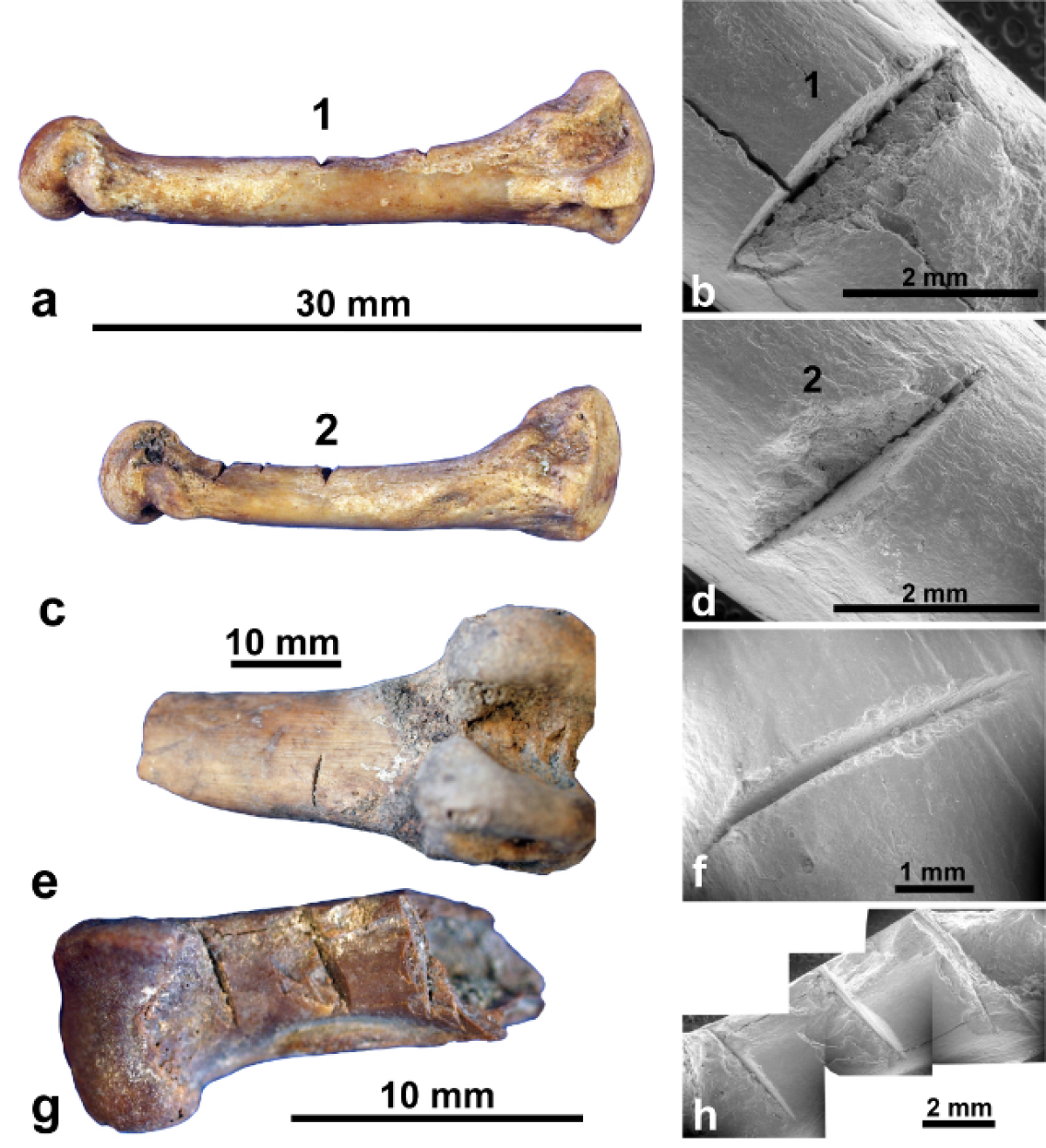

Examination of the remains showed that potential cut marks in bones dated before 1,200 years ago were actually animal bite or gnawing marks, or chop marks from the excavation, indicating that human activity only appeared after that time.

"Analysis of damage on these specimens, including by scanning electron microscopy, showed almost no marks that could be attributed to butchery, and the few that were convincingly anthropogenic came exclusively from material dated later than 600 A.D.," Anderson said.

The researchers also came to the same conclusions when they re-examined bone damage, thought to be man-made cut marks, in samples from old collections. The results confirmed previous evidence that megafauna on the island started becoming extinct around 1,200 years ago.

"We concluded that arguments for early human colonization of Madagascar based upon megafaunal bone damage are poorly supported by the evidence," he said.

The study suggests that the prehistoric colonization of Madagascar began between around 1,350 and 1,100 years ago, and that hunting eventually led to the demise of the larger animals on the island.

The results have significant implications for understanding the history of human migration in the region, according to Anderson, raising questions about why transoceanic voyaging began so late in the Indian Ocean, considering that organized coastal shipping had begun there earlier than in the Atlantic or Pacific.

"We suggest that this might reflect an early adaptation in the Indian Ocean to monsoon voyaging rather than use of the trade winds," he said.

Michael Parker Pearson, an archaeologist with an interest in Madagascar from University College London, who was not involved in the latest research, is supportive of the results presented in the new paper.

"It very much coincides with our research results in previous years—there now seem to be good grounds for being suspicious of dates before 1,500 or so years ago," he told Newsweek.

Not everyone agrees with the conclusions, however. James Hansford, from the Zoological Society of London, who was also not involved in the PLOS ONE study, recently published a paper suggesting that humans first arrived in Madagascar more than 10,000 years ago.

"Unfortunately due to the timing of this study, [the researchers] were unable to include the findings of our research, which were published in the journal Science Advances in September 2018," he told Newsweek.

"The butchery marks we found on the bones of what was once the world's largest bird show that humans arrived on Madagascar 10,500 years ago, more than 6,000 years earlier than previously thought, results that were corroborated by several experts in the field and meet the verification criteria proposed in this new paper."

This article has been updated to include additional comments from James Hansford and Michael Parker Pearson.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.