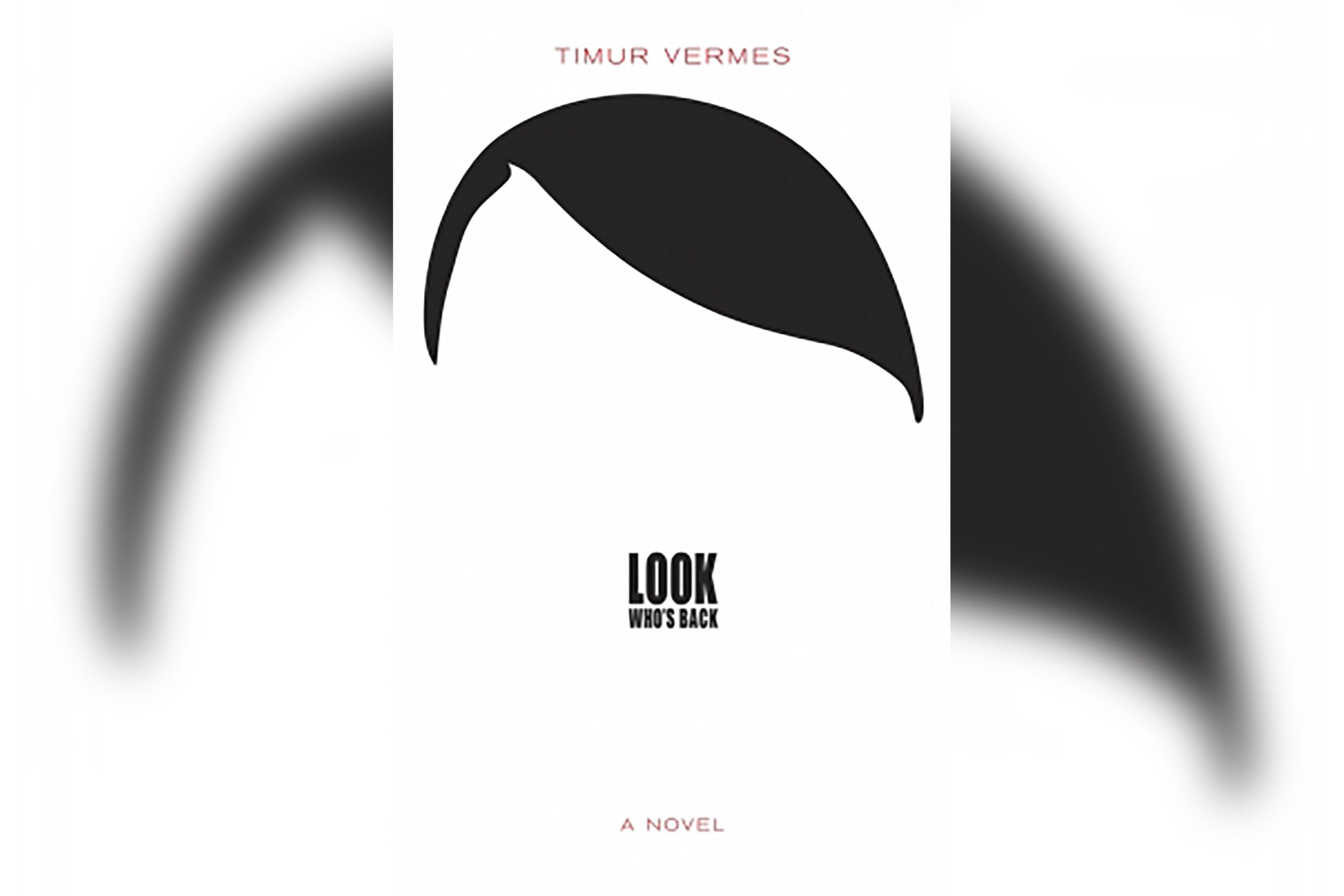

It's a summer day in 2011 Berlin, and Adolf Hitler has just woken up in a vacant lot in a quiet residential neighborhood. He's 56 years old, in full military regalia and doesn't remember anything about his own death. Cue laugh track.

Released in 2012, Look Who's Back (or He's Back, if translated literally from the original German) has sold 2 million copies in Germany and has been translated into 42 languages. An English translation was published in the U.S. earlier this month, and while there has been much debate over whether or why it's appropriate to laugh at Vermes's relentless Hitler satire, this well-researched and uproariously cringe-worthy book makes it hard not to.

To his credit, the Hitler of 2011 is impressively adaptable to his new surroundings, and his pedantic and deadpan delivery is the hallmark around which the novel is built.

I turned my head and saw that I was lying on an area of undeveloped land, surrounded by terraces of houses. Here and there urchins had daubed the brick walls with paint, which aroused my ire, and I took the snap decision to summon Grand Admiral Dönitz. Still half asleep, I imagined that Dönitz must also be lying around here somewhere. But then discipline and logic triumphed, and in a flash I grasped the peculiarity of the situation in which I found myself. I do not usually camp out.

It's important to Vermes's mission that Hitler is—from the start and however improbably—likable. And not in a lowest-common-denominator, South Park kind of way; although, of course, his uniform and signature hair and mustache play their part. Rather, this Hitler is somehow sympathetic, like Beldar in The Coneheads, Buddy in Elf or Link in Encino Man. At first glance, Look Who's Back is a slapstick, madcap "Hitler travels to the future" setup, with all the low-hanging comedy fruits that implies. Hitler mistakes his television set for "a means of storing my shirts overnight without them creasing." After watching commercials, he believes all stores "belonged to a group called W.W.W." He calls the Internet the "Internetwork," becomes obsessed with Wikipedia and discovers the power of "U-Tube."

The public, naturally, believes this Hitler to be a dedicated Führer impersonator, and his commitment to his bizarre brand of improv comedy earns Hitler a TV show slot and instant "U-Tube" fame. Thus does Hitler's acclimation to the new world go from tentative to full-throttle. During one emblematic exchange, his young, slang-spewing assistant tries to help him set up an email account.

'Adolf dot Hitler's gone. As is Adolf Hitler all one word and Adolf underscore Hitler, too.'

'What do you mean, "underscore"? There's nothing "under" about me. I am a member of the master race, not some kind of Slav!'

'AHitler and A dot Hitler have both gone too. Just Hitler and just Adolf as well.'

'Then we will simply have to get them back.'

'You can't get anything back.'

'Bormann could! How else would we have got all those houses on the Obersalzberg? Do you really imagine it was uninhabited beforehand? No! People were living there, but Bormann had his ways and means…'

'Would you rather Herr Bormann sorted out your e-mail address?'

The general assumption that Hitler is Method acting allows him to get away with an admittedly close-to-home brand of humor, but his growing popularity also sows controversy. With "routines" that cover immigration, abortion and racial superiority, comedy Hitler is saying little different than actual Hitler, and the public can't help but notice. "The nation is stumped. Is this humour?" asks one headline.

This is where Look Who's Back succeeds, even after the cheap-shot comedic effect has worn off: It is ultimately a sort of commentary on Hitler's first ascent to power—on the point at which a charismatic man starts being taken seriously, and what that transition entails.

Look Who's Back has one unavoidable weakness. Hitler was a real person, with real history; even the most lowbrow jokes in the novel are suffused with references to that history. It's part of what makes the novel great. But it's difficult to imagine real historical Hitler readily adapting to the social and political realities of 21st century Germany, or Earth, and thus equally difficult to imagine an ultimately redemptive character trajectory for our fictional Hitler. This Hitler is easy to laugh at, sometimes even with, but he's still Hitler. A book whose denouement includes a new ascension of the Third Reich would be a different book entirely. Likewise, to make Hitler truly assimilate with the modern world would be to detract from the very accuracy of voice and worldview that Vermes works so hard to create. And so in some sense, this book's ending is written before it begins. But the getting there is laugh-out-loud funny.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kira Bindrim manages editorial operations for Newsweek and Newsweek.com. She also reviews books at SorryTelevision.com and has one more cat than is socially acceptable.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.