Updated | Sitting in a car parked outside an Albertsons supermarket, Ronda Hampton was sobbing. "I can't do this," she cried, holding a bouquet of flowers, afternoon shoppers pushing past us, the Santa Monica Mountains aflame with sunlight in the distance. Chip Croft, a documentarian, made some feeble attempts to calm her down, but Hampton kept crying, so the three of us sat there awkwardly, two white men somberly watching a black woman wail over the death of another black woman.

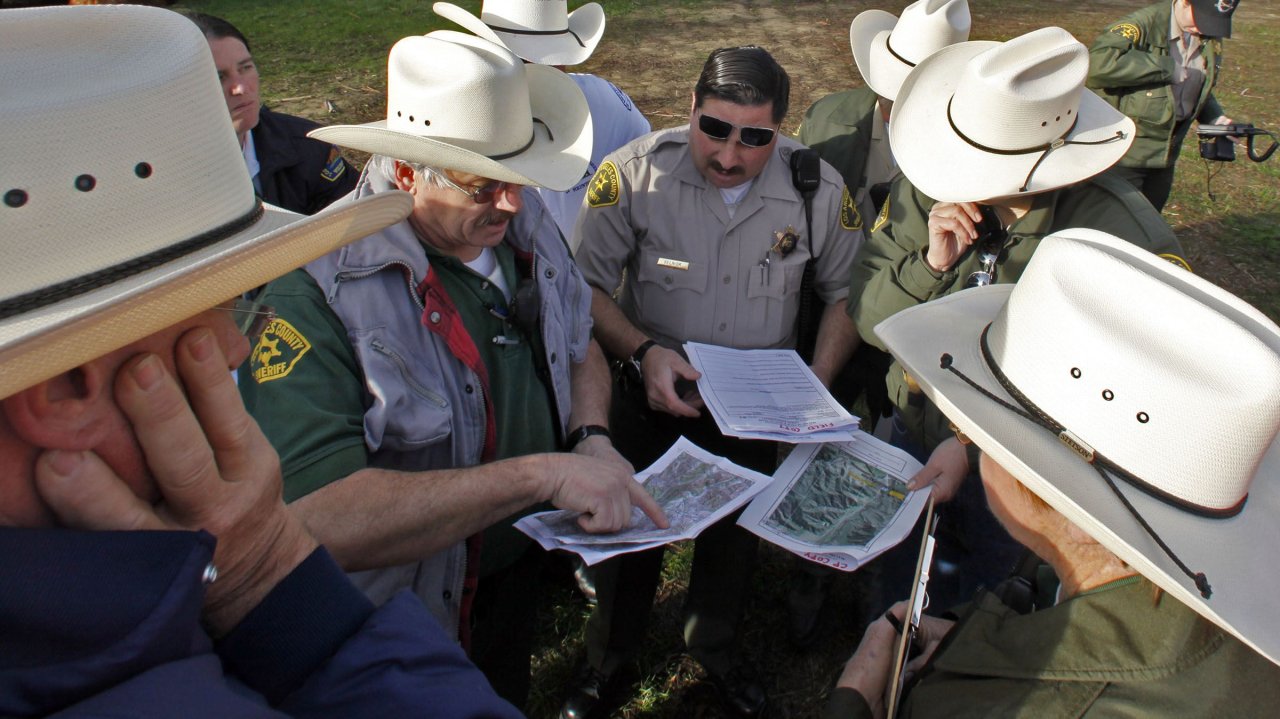

After a time, Hampton's tears subsided, and we headed off into the hills of Malibu Creek State Park, around where the 24-year-old Mitrice Richardson disappeared on September 17, 2009, several hours after being released from police custody in the middle of the night. Croft, who did not know Richardson but recently made a documentary about her with Hampton, drove, at times pointing out where celebrities lived, as if we were on one of those Hollywood tours.

Richardson had been arrested at a popular restaurant on the Pacific Coast Highway, just down the road from the beachfront estate of Steven Spielberg; Los Angeles County sheriff's deputies towed her car and took her inland to the Malibu/Lost Hills station, close to the Albertsons where Hampton broke down. That's the station made briefly famous in 2006, when Mel Gibson was transported there after being pulled over for drunken driving. Deputies eventually escorted Gibson from Lost Hills to his towed car; the department tends to treat the famous with deference. Richardson had competed in beauty contests, but she was not a celebrity. She was released into the night at 12:38 a.m. without money or phone, expected to hike the 11 miles to the tow pound, which is on the Pacific coast.

Richardson was last seen the following morning in a residential area of the Santa Monica Mountains called Monte Nido, near the house of retired television news reporter Bill Smith, not far from the vast estate of Will and Jada Pinkett Smith (no relation). Richardson's half-decomposed body was found several months later, in a remote stretch of the park called Dark Canyon, the clothes she'd been wearing scattered nearby. Some law enforcement officials surmised that Richardson, who suffered from bipolar disorder, walked into the canyon, took off her clothes and succumbed to anaphylactic shock from extensive poison oak exposure. This is highly unlikely, but so is every other hypothesis about her death: violent vagrants, drug cartels, neo-Nazis. Nobody knows anything, though most everyone suspects something. The most grave of these suspicions are aimed at the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department (LASD).

Mitrice Richardson was a young woman who became a case but also cause. To many in Los Angeles, she is a symbol too, as potent as Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, or Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York, of a law enforcement culture that has grown contemptuous of both laws and men. "I consider Mitrice Richardson to be a victim of police brutality," says Jasmyne Cannick, a Los Angeles journalist who writes frequently about race.

To those familiar with the LASD, everything about the handling of the Richardson case is horrific, but none of it is surprising. "The Sheriff's Department is much worse than LAPD," one lawyer said in a Knight Ridder investigation into the LASD. That was in the summer of 1991, blurry footage of Rodney King being beaten by four Los Angeles Police Department officers haunting the nation. The lawyer continued: "A growing joke in our circles is you never would have had the Rodney King videotape if they were sheriff's deputies, because they just would have shot him."

The sheriff at the time was Sherman Block, who died in 1998 and was replaced by Leroy "Lee" Baca, who had spent three decades rising steadily through the LASD ranks. The department was his from 1998 until 2014.

Now, though, Baca is probably headed to prison for lying to federal investigators looking into abuses in the jails run by his department. Because he took a plea deal, the sentence, to be doled out in May, won't be longer than six months. The sentence for Baca's longtime undersheriff, Paul Tanaka, who was convicted earlier this month on a similar array of charges, could be up to 15 years. Neither man had any direct connection to Richardson's disappearance, but the secrecy, tribalism and cynical dishonesty that tarnished that investigation have manifested elsewhere: in the horrific abuses in the Los Angeles jail system, the nation's largest, which the LASD operates; in the racial profiling by LASD deputies across the Antelope Valley; in charges of fawning favoritism for celebrities but often belligerent disdain for the average citizen.

Bob Olmsted, a former LASD commander who mounted a failed bid for the department's top spot in 2014, tells me the men in charge of the department had an modus operandi for all potentially troublesome situations: "lie and deny."

"They destroyed the organization," he says of Baca and Tanaka. "They destroyed the public trust."

Incoherent, Rambling, Troubling

In the car with Croft and Hampton, a lighter mood returned as we climbed into the untarnished sunlight of a Southern California afternoon, toward the place where, on August 9, 2010, Richardson's remains were found by park rangers looking to see if marijuana growers had returned to Dark Canyon. Eventually, Croft stopped the car. From the side of the road, a dirt path wound down toward the canyon floor, where Dark Creek trickled weakly beneath a thick cupola of tangled branches. Croft stayed with the vehicle while Hampton and I descended into the thicket. Scaling boulders and beating back brush, we both fell several times, and Hampton broke her hiking cane. We finally turned back, unable to reach the place where Richardson died or, given its rugged remoteness, more likely was taken after she'd been killed.

Hampton is a psychologist from Pomona, on the east side of Los Angeles County. She has a daughter of her own, but she has devoted the last seven years to searching for the truth about what happened to Richardson. The bond between the two women was originally professional: Richardson was an intern at Hampton's private practice during her senior year at California State University, Fullerton, starting in the fall of 2008. She graduated that winter and seemed to be enjoying the freedoms of post-collegiate life: living openly as a lesbian, seeing a woman and working as a dancer at a gay-and-lesbian club in Long Beach. With Hampton's encouragement, she was applying to graduate school for psychology. She wanted to work with children.

Pepperdine was among the schools Richardson was considering. Situated on a hill above the Pacific Ocean, the private Christian university in Malibu boasts the campus God would have built if he only had the money, as a famous quip has it. Hampton thinks Richardson may have driven to Malibu for a campus visit that afternoon, but it's hard to know what she was thinking. In the days leading up to her disappearance, Richardson was quite obviously suffering through a manic episode. Her last Facebook posts were incoherent and rambling, evidence of a mind coming apart. "There's signs everywhere," she said in one, following it with a smiley-face emoji. In another, she wrote, "I just wanna sleep lol, but u know me and my crazy ideas...lets see where they take me." Again, a smiley face.

Three nights after she wrote those words, Richardson was in Malibu—maybe to check out Pepperdine, maybe for some other reason, maybe for no reason at all. Around 7 p.m., she pulled her Honda Civic into the parking lot of Geoffrey's, a restaurant on the Pacific Coast Highway that has more recently hosted the likes of Rihanna and Kim Kardashian. Richardson, who lived with her great-grandmother in South Los Angeles, was now 40 miles from home, alone in a part of the city not famous for its kindness to wayward strangers.

As the valet was parking Richardson's car, he noticed she had climbed into his car, where she was rummaging. When confronted, Richardson announced that she'd come to avenge Michael Jackson's death. Richardson proceeded into Geoffrey's, where she ordered a steak and a cocktail. There was a group of seven diners sitting near her, and Richardson joined them, acting bizarrely but not threateningly. The first true trouble arrived with the bill: $89.51, which Richardson could not pay. Management decided to call the police. "We have a guest here who is refusing to pay her bill," said the hostess, "and we think she may… She sounds really crazy. She may be on drugs or something."

Several minutes later, three LASD deputies arrived. They called Richardson's great-grandmother, who offered to pay the bill, but that would have required faxing an image of her credit card, which she was unable to do. The officers searched Richardson's car, where they found a small amount of marijuana, as well as bottles of vodka and tequila, along with half a case of beer. They gave her a field sobriety test. She passed.

Based on what they knew and witnessed of her behavior, the officers had sufficient reason to place Richardson under an involuntary psychiatric hold, but that would have required a lot of paperwork and, likely, a trip to a hospital. So instead, they took her to Lost Hills.

Sheriffs in Gangs

Lost Hills is one of 23 stations operated by the LASD, the fourth-largest police force in the nation, after those of New York City, Chicago and the city of Los Angeles. The LASD is a county-wide department, and the effect is somewhat like Manhattan having its own police force and the rest of the New York metropolitan area having another one. Except that the LASD also runs seven jails, including Twin Towers Correctional Facility, the largest jail in the entire world. The LASD also polices the complex spiderweb of public transportation in Los Angeles and contends with both heavily urban environments like East Los Angeles and utterly undeveloped, rugged terrain in the Santa Monica Mountains, where search-and-rescue operations involving helicopters are common, as are sightings of mountain lions. "It's arguably the most complex law enforcement agency in the nation," says Celeste Fremon, who edits WitnessLA and is writing a book on the LASD.

That complexity makes the department difficult to manage, an intractability compounded by a jurisdiction of 4,751 square miles, which is about twice the area of Delaware. The LAPD must ultimately answer to the mayor of Los Angeles, but the LASD is the main law enforcement agency in 42 different cities and 130 unincorporated communities. That complicates accountability. And obfuscates it. Public scrutiny eventually forced city officials into a reformation of the LAPD, with federal oversight. Its sibling, though, kept on without much notice.

In the 1970s, deputies formed gangs within their stations, each with its own code of extralegal conduct. " Membership swelled in the 1980s at overwhelmingly white sheriff's stations that were islands in black and Latino immigrant communities," reported the Los Angeles Times in 1999. One notorious group, operating out of the Lynwood station, was the Vikings, whom a judge branded a "neo-Nazi, white supremacist gang." Among its members in the 1980s was Tanaka, the disgraced undersheriff, who has a Vikings tattoo on his ankle and does not deny membership in the group, though he says it was not a gang (a lawyer for Tanaka declined to comment for this article or make his client available).

Baca, who became sheriff in 1998, dealt with the LASD gangs in much the same way he dealt with most other problems in the department: by pretending they did not exist. According to the Los Angeles Times, he knew about the gangs but worried that an outright ban in membership "would be unconstitutional." Instead, he simply asked officers to refrain from joining.

In her lengthy profile of Baca for Los Angeles Magazine, Fremon noted that his idealism and detachment earned Baca the nickname "Sheriff Moonbeam" ( his closeness to the Church of Scientology might have also contributed to that image). Some men are obviously evil; Baca is not, but he was obviously oblivious—and his officers knew it. Much of the department was run by the man Fremon called Baca's "most trusted subordinate," Tanaka. He became, she tells me, "the shadow sheriff. He was the most powerful person in Los Angeles that nobody had ever heard of."

'Heil Hitler' Salutes

Hampton, something of an LASD watchdog, says the two stations most eager to operate under their own rules were Lost Hills and Lancaster, in the high desert on the county's northwestern edge. "These guys got vigilante justice going on," she says of them. "They do whatever they wanna do."

In 2013, the Department of Justice found that the Lancaster station and another in the Antelope Valley, Palmdale, "engage in a pattern or practice of unconstitutional and unlawful policing regarding stops, searches, and seizures, excessive force, and discriminatory targeting of voucher holders in their homes." The targets were black and brown residents, most of them poor. An especially harrowing practice was "voucher enforcement" in public housing, wherein deputies "would routinely approach the voucher holder's home with guns drawn, occasionally in full SWAT armor." The Justice Department argued that these raids were "carried out with the intent that African-American voucher holders leave Antelope Valley."

Residents say things are better now, but suspicions about the desert stations remain. In 2015, Los Angeles Magazine presented a convincing case that a Palmdale deputy, Jon Aujay, was murdered in 1998 by colleagues after discovering a methamphetamine-dealing operation. The author of that story, Claire Martin, said in an accompanying interview that "allegations against deputies ranged from fraternizing with cartel members, to warning them of investigations, to operating meth labs with them, to murder."

Deputies across the department have been investigated for a staggering panoply of crimes, including "rape, smuggling heroin into a lockup, stealing money from a narcotics bust, smuggling undocumented immigrants and even using a Los Angeles Sheriff's Department helicopter for unofficial business," according to a Los Angeles Daily News review of an internal LASD report from late 2013. The heroin in question was hidden inside a burrito.

Compton and Century, both in South Los Angeles, were also problem stations: Their excesses would have made an easy target for Black Lives Matter. In 2003, Century deputies fired 81 shots at Deandre Brunston, killing him. They thought he was holding a weapon. It turned out to be a sandal. In 2005, deputies from Compton station fired 120 shots at a fleeing suspect, Winston Hayes. Hayes survived and won a $1.3 million judgment from the LASD. Olmsted says that, earlier this decade, the two stations were known to attract deputies who'd honed their taste for violent confrontation by working in the Men's Central Jail.

As the desert obscured the wrongdoings of Palmdale and Lancaster, the Santa Monica Mountains did the same for Malibu/Lost Hills, a low and featureless station house on a bland commercial strip that quickly gives way to roads twisting through canyons. The station has the feeling of an outpost, like some forlorn forward operating base in the Hindu Kush. Here, as there, cultural conflicts are inevitable. The officers of Lost Hills are tasked with policing a population that has a potentially toxic combination of power, money and fame. The residents of Malibu are far more comfortable giving orders than taking them.

Sometimes, the cultural divide between the deputies of Lost Hills and the citizens they policed showed itself in outright contempt. In 2009, Ed Meyer's 15-year-old son was arrested for violating a curfew. Meyer, concerned with the boy's treatment by deputies, went to Lost Hills to complain. The deputies grasped that he was of Jewish descent and, allegedly, began to make "Heil Hitler" salutes and speak in a mock-Yiddish accent. "Lost Hills can be compared to an ongoing frat house," Meyer tells me.

Parallels between Lost Hills and Animal House suggest serious indiscretions but perhaps not felonious ones. The Hollywood Reporter offered a more disturbing cinematic comparison. "The Lost Hills station is just like the movie The Departed ," an anonymous insider told the magazine, alluding to the 2006 Martin Scorsese film about corruption in the Massachusetts State Police. The Reporter 's story was about Steve Henneberry, a bodybuilder who starred in the American Gladiators television franchise. Henneberry and his wife, the former actress Tracy Justrich, lived in Agoura Hills, where they were part of a "tightly knit community" that included many LASD deputies, according to The Reporter . That closeness proved a detriment when Justrich accused Henneberry of abusing her and their children. The deputies downplayed her complaints; "maybe it's just his parenting style," they allegedly counseled.

Justrich fled the deteriorating marriage with Henneberry and began seeing Lawrence Collins, a battalion chief with the Los Angeles County Fire Department. The two of them are now married, but it is matrimony without tranquility. Collins says that because of Henneberry's endless harassment, he and Justrich have had to move hundreds of miles away from Los Angeles, though he still works there. "The arrogance of so many LASD members," Collins wrote in a letter to the department, "who seemed to have become convinced they are a law unto themselves, gave some of them license to break the law and even to protect violent criminals."

The letter charges that Henneberry may have supplied steroids to Lost Hills deputies. Captain Christopher Reed, a spokesman for the department, tells me there have been "absolutely" no Lost Hills deputies caught using or dealing steroids, but I've heard whispers about it from others. Olmsted, the former commander, believes steroid abuse is "rampant" in the LASD. One former Lost Hills deputy, Edwin Tamayo, also found the allegations credible. "All I know is that some of the guys who were skinny twigs all of a sudden got huge," he says in an email.

Tamayo, 46, came to the LASD from the Stockton Police Department in 2000. Seven years later, he arrived in Lost Hills. Six years after that, his career in law enforcement effectively ended when he was found to have fixed traffic tickets. I recently spoke to Tamayo and his lawyer, Jacob Glucksman, and Tamayo describes a culture in which deputies were expected to fundraise for politicians deemed favorable to the department. It was the same frat house that Meyer describes, only more venal and nefarious. Shortly before Tamayo was relieved of duty for fixing tickets in 2013, Captain Joseph Stephen was removed from the command of Lost Hills for allegedly participating in the sexual harassment of a female deputy.

Tamayo was at Lost Hills when Richardson went missing, but he is not familiar with the particulars of her case. But like many others in law enforcement, he remains mystified by the actions deputies took—and failed to take—that night.

"I don't know," he says, "why she didn't get a ride home." The Los Angeles Times partly answered the question in a 2009 editorial about Richardson in which it noted that the "Sheriff's Department can't be a taxi service." Mel Gibson appears to have been a notable exception.

'It's Crazy Out Here'

Latice Sutton, Richardson's mother, called the Lost Hills station around 10 p.m. "I'm her mother," she said, "and are you guys gonna book her and release her on her own recognizance tonight? Because it's dark, she doesn't have a car, and I don't want her wandering."

Sutton did not sound nervous, judging by recordings of the call. "I think the only way I will come and get her tonight—if you guys gonna release her tonight," Sutton said. "She's not from that area and"—here Sutton's voice rose—"I would hate to wake up to a morning report: 'Girl lost somewhere and her head chopped off.'"

"You don't have to worry about her safety," the deputy assured her.

"I feel safe with her being in custody," Sutton said, at which the officer laughed. "It's being released that I'm worried about. It's crazy out here."

A little after midnight, Richardson was released into the inhospitable darkness of the Santa Monica Mountains. All businesses near the police station had been long closed. Public transportation, never a safe bet in Los Angeles, was nonexistent. She was 11 miles from her car at the Malibu tow pound. The walk would have taken her up and down hills, through a tunnel, along the shoulder of a highway wending through the mountains. Home must have seemed as distant as the stars above.

At 6:30 that morning, Bill Smith called the Lost Hills station. "We had a prowler walking around through the backyard here, but we don't know what the situation was." He suggested the deputies "do a little drive-by or something." He told the dispatcher that the prowler had been "sitting kind of sprawled out on these wooden steps at the back of the house" but had now disappeared into the wilderness that surrounds Smith's house. Though the woman never identified herself, it was almost certainly Richardson. She was never seen alive again.

Partially Decomposed

"I think she made a horrible decision," Michael Richardson tells me, speaking one night in March when I met him at a cigar lounge on La Brea Avenue. He thinks his ex-wife, Sutton, should have driven to Malibu and collected their daughter. "You do not leave your child with these people," he says.

Michael Richardson has been in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles for the past 24 years, but his accent has the twang of Texas, where he is from, and the lilt of Alabama, where he also lived. After high school, he did some time for robbery, but he has since straightened out and now works in a hospital. Although nobody can say with any confidence how Mitrice Richardson died, her father has ideas about what happened between the deputies and his attractive, vulnerable daughter. "These guys wanted to have some fun," he says.

The department offered plenty of fuel to keep such suspicions at a steady burn. It at first said there was no surveillance tape of Richardson exiting the station, with Captain Thomas Martin averring in an October 2009 email that "there is no video or tape of any kind," according to the Malibu Surfside News, a tiny local paper whose Anne Soble assiduously reported on the Richardson case. But then, five months later, Martin produced the tape, claiming that it had been sitting in his desk, as if it were merely an extra stapler accidentally squirreled away. According to Richardson's mother, the tape shows her daughter in obvious psychological distress inside an intake cell. "She clutches at the mesh screening and is rocking side to side like a small child," Sutton says. Yet the jailer, Sheron Cummings, simply released Richardson.

The tape also reportedly shows a deputy leaving the station right after Richardson was released. In a meticulously reported feature for Los Angeles Magazine, investigative journalistMike Kessler was able to identify and contact the deputy who, according to Kessler's account, lied about having been at Lost Hills while Richardson was there. In a subsequent conversation, the deputy (who was not named in the article, and whom I was unable to contact) told Kessler that while he may have been there, he did nothing wrong: "The night this nonsense happened, I was one of the guys that keptaway from this, minding my own business."

I called Sheriff Baca, who will be sentenced on May 16, and asked him to explain what he knew about Richardson's disappearance. "I am not confident that I can explain what occurred during that time," he says. He sounded older than he looked in photographs. In a follow-up email, I asked if there had been systemic problems in the LASD and whether Richardson could have been among the victim of departmental venality.

"I shared all I know," he wrote back. "It was tragic."

That much, few will dispute.

The discovery of Richardson's body on August 9, 2010, in Dark Canyon is nearly as troubling as her disappearance. The terrain is wild, inhospitable and would have been especially so to a city girl wearing a Bob Marley T-shirt, jeans and sneakers. The remains were on a hillside, partially mummified, the clothes removed. "It sounds like someone abducted her, killed her and at some point dumped her body," an LAPD detective told Kessler of Los Angeles Magazine.

That would make the floor of Dark Canyon the site of a potential homicide, but the deputies did not treat it as such. The proper protocol would have been to wait for the coroner, so that the remains could be photographed, the site inspected for clues and a crime scene established. Instead, against explicit orders, the deputies bagged Richardson's remains and airlifted them by helicopter. The coroner found this an inexplicable decision, the Los Angeles Times reported, insisting that "he was 'very clear' with sheriff's officials and could not think of another case in which a police agency had moved entire skeletal remains without coroner's approval."

The coroner was not able to determine how Richardson died, but two reports by the Office of Independent Review found the LASD not culpable for Richardson's death. The LASD was also cleared by the OIR of any wrongdoing in how it handled the discovery of her remains a year later. But as Olmsted, the former LASD commander who was recently branded "one of the most important whistleblowers in the history of Los Angeles," tells me OIR's integrity was compromised by a proximity to the LASD's most powerful figures. Hampton also filed a dozen complaints about various LASD deputies involved in the Richardson's case. Nine of these were registered with the Internal Criminal Investigations Bureau, which Hampton believes minimized their seriousness by treating them as "service complaints," not matters of potential criminality. The head of ICIB at the time was Captain Tom Carey, a Tanaka loyalist who faced obstruction of justice charges last summer. Tanaka had instructed deputies to work in "the gray areas," the indictment against him and Carey alleged. This was the law enforcement equivalent of some uncharted borderland, one that would prove maddeningly impenetrable to a civilian like Hampton.

In the summer of 2011, a year after her remains were found, Richardson's parents settled for $900,000 from the LASD, which they split. Her father, however, continues to seek a criminal investigation into her death. In letter to California's attorney general, Kamala Harris, Michael Richardson struck a personal note. "You see, Ms. Harris," that letter says, "I look at you and I see Mitrice Richardson. A young, intelligent, smart, black, and beautiful young lady who busted her butt in school to one day become someone who could be helpful and make a difference."

In February, Michael Richardson got a response: The attorney general agreed to investigate the disappearance of his daughter.

Routine Beatings

Four months after Mitrice Richardson's body was found, some LASD sheriffs attended a Christmas party Fremon called in her Los Angeles Magazine article the "starting point for the department's public downfall." At the party, a fight began between two LASD gangs working at the Men's Central Jail: the 3000 Boys and the 2000 Boys, the names referring to the cliques' respective floors. Local police became involved; efforts by a Tanaka henchman to suppress reports of the incident failed and, as Fremon wrote, images "of tattooed deputy gang members running the jails and issuing group thumpings to anyone who crossed them" quickly found their way into local news reports.

There was much more to come. In the fall of 2011, the American Civil Liberties Union released its annual report on the city's jails, noting a "pattern of severe and pervasive abuse of inmates" and calling for Baca's resignation. Baca met with the editorial board of the Los Angeles Times and, in his defense, pleaded ignorance: "I wasn't ignoring the jails. I just didn't know."

Nothing was quite as astonishing as the case of Anthony Brown, a jailhouse informant who had been working for the FBI. When deputies discovered in mid-2011 that he had a cellphone he'd used to contact federal agents, they began an intricate operation to move Brown from jail to jail, disguising his name and doing everything they could to hide him from the FBI. Deputies even went to the home of the FBI agent in charge of the investigation, trying to pressure her into standing down. The effort to silence Brown was called Operation Pandora's Box, and it was ordered by Tanaka, the LASD's second-in-command. Despite his earlier assertions of benevolent ignorance, Baca's plea deal is effectively an admission that he knew about the scheme.

In seeming defiance of the negative press surrounding the LASD, Baca was honored with the 2013 Sheriff of the Year award by the National Sheriffs' Association. Several months after that, the Department of Justice indicted 18 deputies. "The pattern of activity alleged in the obstruction of justice case shows how some members of the Sheriff's Department considered themselves to be above the law," said the U.S. attorney in Los Angeles, describing a pattern of inmate abuse, including frequent beatings.

On January 7, 2014, a month after those indictments, Baca resigned instead of seeking re-election for a fifth term. His challenger would have been Tanaka, who had been pushed out of the department but was now running for sheriff, blaming many of the LASD's failures on his former boss.

Earlier this year, Baca pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI as it investigated conditions in the county's jails. If he heads to prison later this spring, it will not be for long.

Tanaka went on trial in March, on charges of conspiracy and obstruction of justice, many of them related to the "hiding" of Brown. "The allegations in this indictment include cover-ups, diversionary tactics, retribution and a culture which is generally reserved for a Hollywood script," an FBI agent said at a news conference. Tanaka was found guilty on all federal charges.

Captain Reed, the department spokesman, referred me to a statement that says, in part, that the LASD is aware of the California Department of Justice's investigation and is cooperating fully. The statement also notes that "all past leads have been exhausted," which one could take to be a good-luck-with-that to Attorney General Harris.

Lieutenant Darren Harris, another spokesman for the LASD, tells me new procedures have been implemented at Lost Hills. Arrestees released from jail are now given the option to wait in the station until morning.

I asked Hampton why she has invested so much time and money and energy in the case. We had discussed at length minute details, but this central question had for some reason eluded me. The motivation of Richardson's parents is obvious, as is that of Croft, the documentarian. Hampton knew Richardson and knew her well, but there is something outsized in her grief. She cried the first time we spoke on the phone, and she cried several times thereafter.

Hampton tells me that her father died young and that, later in life, she had several people in her life meet a violent end. About those other deaths, she could do nothing. But she is determined that Mitrice Richardson will not be just another victim, written off and forgotten. "I will not sit by and pretend that the answers are not there," she says. "I am tired of death."

Update: This article has been updated to clarify Los Angeles Magazine's role in contacting, but not identifying, a deputy involved in the Mitrice Richardson case.

Correction: This article originally incorrectly stated that deputy Jon Aujay may have exposed a methamphetamine ring. Aujay may have merely discovered one.