Amid the politicking and jostling for votes in Indonesia's intensely contested presidential elections this year, one of the least-expected campaign tactics to emerge was the exploitation of Nazi symbolism.

Weeks before the vote, Indonesian rock musician Ahmad Dhani appeared in a controversial Nazi-themed music video supporting Prabowo Subianto's presidential bid. Singing an adaptation of Queen's "We Will Rock You", Dhani wore a replica of the Nazi uniform worn by Adolf Hitler's military commander Heinrich Himmler, who oversaw the Gestapo and directed the slaughter of six million Jews during the Holocaust. Subianto subsequently re-posted the video on his official Facebook page, commenting: "This video will increase my spirit to fight. Rise up Indonesia!" The video provoked outrage and criticism both at home and internationally. Seemingly bemused by the furore, Dhani later apologised, and his management company removed the video from its YouTube channel.

Just days earlier, a controversial Nazi-themed café reopened in Bandung, less than a year after death threats and a global backlash forced the owner to shut it down. Named after a Second World War era venue in Paris, which was frequented by German soldiers, the Soldaten Kaffee is replete with explicit Nazi iconography.

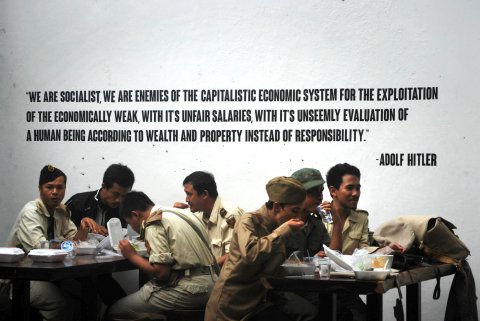

A portrait of Hitler adorns the walls, alongside swastikas, Nazi propaganda posters, and quotations from the dictator. The café's Facebook page also features the number 88 – code for the Nazi "Heil Hitler" salute, as well as a photograph of a soldier with the caption: "I stand on the Führer side."

The café's owner Henry Mulyana, however, insists that the venue does not glorify Nazism. "I'm not interested in Nazi ideology," he says. "I just use Nazi symbols because the theme of my café is the Second World War. "I don't show anything related to violence or victims of war. The Nazi symbol is not forbidden in Indonesia, so I'm not breaking any laws."

Mulyana's apparent confusion about the offence his café causes, and the use of Nazi iconography during Indonesia's election campaign, exposes the nation's complex relationship with far-right ideology, which combines a fascination with a lack of understanding of the history of hatred underpinning Nazi motifs.

"It's not uncommon for Indonesians to say 'I like Hitler' when meeting someone from Germany," says Adrian Vickers, professor of Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Sydney. "There is a view that Hitler was a successful leader who brought Germany out of its pallid state at the end of the First World War. The school curriculum doesn't really teach about the Second World War and the Holocaust, so there's this huge gap in people's knowledge, which goes back to the curriculum during the Suharto period."

Between 1967 and 1998, the anti-Communist New Order dictatorship of Indonesia's second president Suharto maintained its grip on power through engineered elections, censorship, and a centralised, military-dominated government that used its coercive powers to bend civil society to its will. It also sought to brainwash its citizenry by creating a propagandised anti-leftist version of history – the vestiges of which still remain.

"I live in the capital and studied at the best university, and my colleagues have never heard about the Holocaust," says Aditya Rian, a 23-year-old graduate of Jakarta's Universitas Indonesia. "They have no clue about the swastika, Hitler's history, Mein Kampf. We have no clue."

Beneath this veneer of ignorance among the general populace, however, lies a deeper, more unsettling fascination with Hitler and the far-right among some sections of Indonesia's political class. "That fascination has been there for a long time," Vickers says. "It goes back to the pre-war period when the Dutch Nazi party existed. Sukarno [Indonesia's first president], who had both left- and right-wing elements to his demagoguery, had this famous line: 'The year of living dangerously', which was taken from a Mussolini speech. Some Indonesian politicians were fascinated by the Hitler phenomenon and you can see this generally in Southeast Asian nationalist movements."

During the Second World War, Suharto fought against allied troops under Japanese Axis occupation of Indonesia, and in 1943, he joined the Japanese-sponsored militia (Defenders of the Fatherland), where he became indoctrinated with a pro-nationalist, militarist ideology that is believed to have profoundly shaped his thinking. Under Suharto's dictatorship, Indonesia invaded and occupied East Timor in 1975, resulting in the genocide of up to 200,000 people through massacre, starvation, forced relocation and disease. And between 1983 and 1985, up to 10,000 suspected criminals were slaughtered without trial in what became known as the Petrus Killings.

Suharto's 1960s anti-Communist purge, too, led to the deaths of between 500,000 and one million Indonesians – almost all of whom were unarmed. Some were shot by the military, while others were hacked to death by their neighbours under the incitement of army propaganda, and with Western complicity at a time of heightened Cold War tensions.

Subianto's social media endorsement of the Nazi-themed music video is all the more troubling given his close links to Suharto, his former father-in-law.

Subianto's father Sumitro Djojohadikusumo served in government under Suharto's regime and, in 1998, Subianto was dismissed from the military over the abduction and disappearance of democracy activists during anti-Suharto riots earlier that year. "Part of Subianto's presidential campaign was to revive memories of Suharto and make him a national hero," Vickers says.

During his election campaign, Subianto also courted right-wing paramilitary groups such as the Pancasila Youth, featured in the critically acclaimed 2012 documentary The Act of Killing. The organisation grew out of the death squads that killed hundreds of thousands of alleged Communists and ethnic Chinese during Suharto's anti-Communist pogrom. Subianto ultimately lost the election to Jakarta governor Joko Widodo, and in August, Indonesia's Constitutional Court threw out his challenge to the defeat. Widodo hails from a much more modest background. His socialist policies, such as free healthcare and education for the poor, won him widespread support. His election victory is widely seen as a break from the corruption and authoritarianism of past leaders.

"It's a statement that Indonesia has come a long way in its re-birth of democracy," Vickers says. "There's a stronger feeling against the extremist approach to government and a tendency towards a more moderate society. One of the good things to come out of the Dhani scandal was the rejection of that extremism by a lot of Indonesians. It was a bit of a wake up call."