Whenever Nasser Edeeb visits Switzerland, which the 44-year-old businessman from Libya does with some frequency, there are two products he likes to pick up. The first are Swatch watches (for family, friends, himself), the second iPhones (if he decides it's time for an upgrade). It's not that you can't get Swiss watches in Tripoli – they're even cheaper there due to a lack of sales tax – but buying them at the source is special, he feels: "You tell people, this is a Swatch watch that I bought in Switzerland," he says. "It's the emotion, it's the story."

As for Apple products, they can be hard to come by in north Africa – but there's emotion involved here, too. The Apple store on Zurich's Bahnhofstraße feels like home to Edeeb, who finds relief in Switzerland from the political chaos of Libya. "My friends joke that it's my Swiss office," he says. "I always come here right away. I use the time to learn about the latest upgrades – and to charge my phone."

On a Venn diagram of discretionary spending, Edeeb currently occupies relatively uninteresting territory. Loyalty to Apple doesn't necessarily conflict with loyalty to Swatch: Credit Suisse research points out that the rise of smartphones over the past decade has failed to hold back sales of Swatch-branded watches.

And yet some analysts are predicting that, starting this fall, people like Edeeb are going to be pushed by Apple to choose sides. This is because the US tech group is expected to unveil its first smartwatch some time in the next several months, part of a product pipeline that executives have been talking up as the "most exciting in 25 years". Whereas current smartwatch models, such as Samsung's Galaxy Gear Live or LG's G Watch, tend to look clunky or miss out key functions – or both – Apple's design track record suggests it will avoid these mistakes. And whereas only about two million smartwatches were shipped globally across all brands in 2013, Apple suppliers told the Wall Street Journal this summer that executives in Cupertino were preparing to ship 10 to 15 million watches this year.

Annette Zimmermann, a research director of consumer markets and technology with IT advisory firm Gartner, says sales volumes will depend a lot on price "but if it's a good product, they [Apple] could see 10 times the volumes that any other company has shipped".

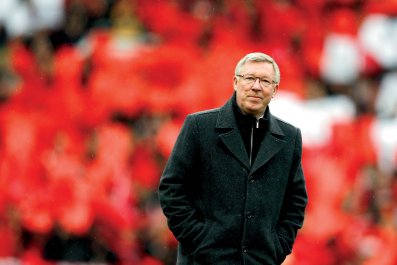

Within the industry, the potential competition with traditional watches is being called the battle for the wrist – and yet leaders in the Swiss watch world dismiss the idea it will be a zero-sum game. When Tag Heuer's sales director defected to Apple this spring, Jean-Claude Biver, the president of the watch division for TAG Heuer's parent company LVMH, told CNBC that "if he would have gone to my direct competitors, I would have felt a little bit betrayed, but if he goes to Apple, I think it's a great experience for him".

Nick Hayek, chief executive officer of the Swatch Group, whose brands range from the inexpensive flagship Swatch to high-end Breguet, Omega and Longines, predicted in March that smartwatches would not replace his company's products because "what you put on your wrist is more than a commodity . . . [smartwatches] don't achieve the most important task of a watch, which is to be a piece of jewellery". And Jean-Daniel Pasche, president of the Federation of the Swiss Watch industry, says: "I would see the smartwatch as complementary to the Swiss watch, not as a substitution. These two types of watches will go their parallel ways."

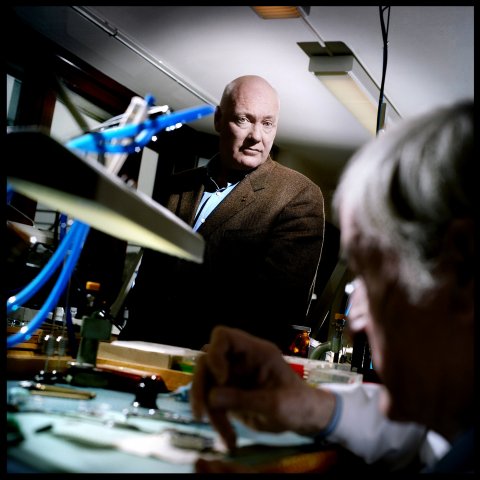

This is a favourite, if flawed, response from businesses facing new competition – witness PC – and chipmakers talking down the threat of tablets. But when it comes to Swiss watches, the logic is, in some ways, sound. After the "Quartz crisis" of the 1970s and 1980s, when cheaper battery-operated watches from Asia and the US undermined the slower-to-adapt Swiss groups' business models – leading to bankruptcies, mergers and job-losses on a massive scale – high-end watches became the much-reduced Swiss industry's growth engine. That strategy has held up over the years, reinforced by a general growth in the luxury goods sector and by the decision to target emerging markets.

The average price of an exported Swiss watch rose from CHF160 in 1992 ($110 at the time) to CHF691 ($760) in 2012, and today higher-priced mechanical watches (average price: CHF2,211) represent about three-quarters of the sales in a more-than $27bn industry, according to figures from Credit Suisse and Euromonitor.

The reasoning goes, then, that customers ready to spend upwards of $50,000 on a single watch are unlikely to see an Apple product – which analysts doubt will cost more than $500 – as a serious alternative. "We don't know what an iWatch is," says Hsu Te Han, a resident of Beijing on a 10-day European tour, as he exited a Patek Philippe store (average wholesale price: CHF22,000) in Munich earlier this month – before conferring with his daughter. "OK, she knows what it is. Teenagers know it. But we bought this for the image, the quality," he says of the watch Mrs Hsu was holding. "And for the investment." China and Hong Kong together accounted for nearly 30% of Swiss watch exports in 2012, and while that demand has slowed in recent years (in part due to a Chinese government crackdown on corruption), the market – and Chinese tourists visiting Europe – remains an important one.

Zurich shoppers also expressed ambivalence about a future iWatch. Ruben Duijn, a Dutch native living in Switzerland, doubted a smartwatch would look good enough for the office. He wears a Rolex to work. Jannov Rusli, visiting Switzerland from Indonesia, confessed, "I'm not an Apple fan anyway." Frank Chan, a Hong Kong native living in Paris who had just bought a Tissot, said: "I hate the idea of having to recharge the battery every night." His wife, Tina Ho, doesn't wear a watch at the moment because their two-year-old son would yank it off. Even if she did, an iWatch would look "too plasticky" for her old job in finance. "Maybe it's something for students," she ventured.

Analysts point out that people who wear watches (an estimated 55% of the US population; figures are harder to come by for Europe or Asia) often own two or three – supporting the Swiss industry's hope that Apple might simply initiate more people into the experience, making the purchase of a smartwatch the first step on the road to Switzerland. But this is also why Annette Zimmermann at Gartner thinks the companies need to take smartwatches seriously: "Obviously the most profitable part of the watch market is the luxury segment, but then you also have huge numbers of models that are moderately priced or low-priced . . . and those will be in competition with an iWatch, especially when competing to be a person's second or third watch."

The Swatch Group, which derives a fifth of its sales from its low-to-mid-price Swatch and Tissot brands, appears alert to the danger and announced in late July that Swatch Touch watches would incorporate fitness-tracking features from next year. The group could also benefit from other companies' smartwatches thanks to its role as a parts supplier – including through several subsidiaries that make parts for electronic goods.

Still, a wait-and-see approach is perhaps wise, given it is unclear what an Apple smartwatch might feature – and look like. Tim Cook, the company's chief executive, has frequently praised Nike's FuelBand, suggesting an Apple product will also offer fitness features. (Cook sits on Nike's board of directors). And when the company released the iPhone 5S last year, insiders pointed out its M7 motion-sensor chip would let the company test a technology that would play a central role in future wearable devices.

Zimmermann predicts an iWatch – or iTime, as some have speculated it will be called, to avoid any clashes with the previously trademarked iSwatch – will work in concert with iPhones, iPads and Macs rather than have its own satellite connection. As for design and market positioning, the company seems to be looking for advice from the luxury sector, hiring not just TAG Heuer's sales director but also Angela Ahrendts, the former chief executive of Burberry. Might Apple, hyper-conscious of the power of brand, want to find a way to slap on the much-admired "Swiss Made" label? Maybe, but it would be a challenge: new Swiss laws raise the bar on what it takes to make that boast. Before, 50% of the value of the product had to be made in Switzerland, but starting next year, that number will be 60%.

That means that, in Zurich, Bahnhofstraße's Swatch shop will probably hold more sway than the Apple store on the likes of Tim Jones, a Melbourne-based engineer. Jones spent the last hour of his holiday choosing a Swiss watch for his girlfriend, though he wears a fitness band and carries an iPhone. "If I could have it all in one, would I buy that?" he asks. "Absolutely."