The drive from the San Francisco Bay Area to Manzanar, the former Japanese-American internment camp in California's remote Eastern Sierra region, takes about seven hours. There is no other way to get there, and there is no way to make the drive shorter. For most of the way, I listen to an audiobook: Rick Perlstein's The Invisible Bridge, about the improbable rise of a B-movie actor to the presidency of the United States.

In 1988, the final full year of his second White House term, Ronald Reagan apologized to the 120,000 Japanese-Americans who'd been confined to internment camps during World War II, of which there were 10 around the nation, and of which Manzanar is the most notorious. The survivors of the camps also received reparations, a rare concession by the American government. "Here we admit a wrong," Reagan said. "Here we reaffirm our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law." The announcement was made in San Francisco, whose Japantown was cleared out by interment, which began in 1942, about three months after Pearl Harbor.

Some of the survivors of the camps, many of them now aged, watched as Reagan, in a mustard-colored suit, apologized for the sins of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

"I think this is a fine day," the president added.

Three days before I went to Manzanar, President Donald Trump had ordered a halt on immigration from seven majority-Muslim countries. He did so via executive order, numbered 13769. Manzanar was created via Executive Order 9066, which will turn 75 years old on February 19. The order did not mention the Japanese, but its intention was very clear.

"It's in no way a concentration camp," said one newsreel that showed Japanese-Americans disembarking buses with their suitcases in the high desert of Inyo County, where the rudiments of Manzanar awaited (they would have to build a good deal of the camp themselves).

"To be clear, this is not a Muslim ban, as the media is falsely reporting," Trump said as protests to his executive order mounted.

Another newsreel: "They are merely dislocated people."

The town closest to Manzanar is called Independence, from nearby Fort Independence, erected in the 19th century to protect white settlers from attacks by Native American tribes who may have thought they had some claim to this land, having lived on it for a thousand years, if not longer. Today, there is an Indian reservation called Fort Independence, where Paiute Indians hold on to a shred of what was once theirs. They operate a gas station that doubles as a casino. It appears to be the most successful commercial enterprise for many, many miles.

Inyo County, which hugs California's border with Nevada, is the ninth-largest county in the country. It is dramatically beautiful, cradled by the Inyo and Sierra ranges, the light always playing off the mountains in surprising ways. It is also Trump country: Though fewer than 8,000 people in the county voted, they did so overwhelmingly for the Republican candidate.

The sympathies of the local populace are apparent at a coffee shop in Lone Pine, nine miles south of Manzanar. Hearing me approach customers with questions about Manzanar and the Trump immigration ban, the proprietor—a burly, mustachioed guy—tells me to shut off my recorder. Satisfied, he returns to watching Fox News, where a blond pundit is defending the travel ban.

At one table, there are several middle-aged men. Each has in front of him an unopened copy of that morning's Los Angeles Times . One of them is crunching on an immense carrot partly wrapped in foil.

I ask about Manzanar.

The man with the carrot says he's been to Japan, but not to Manzanar, because.… He doesn't finish the sentence.

The oldest man at the table has a thick white beard. He is hunched over a mathematics textbook, working out what appear to be some pretty complicated network theory problems. He didn't seem to be paying attention, but now he looks up. Manzanar, he says, was "asinine."

He adds that two recent developments have brought him joy: the end of California's five-year drought and the election of Trump.

I ask the question I've come to answer: Isn't Trump taking us to a place as asinine and profoundly un-American as Manzanar? Will we someday have to build a museum to Syrian refugees at the international terminals of LAX and JFK airports?

No, the amateur mathematician says. The media have got it all wrong. He points at the television screen: "Parrots!" he shouts.

Then he points at the plump copies of the Los Angeles Times on the table: "Parrots!"

Finally, he points at me. "Parrot!"

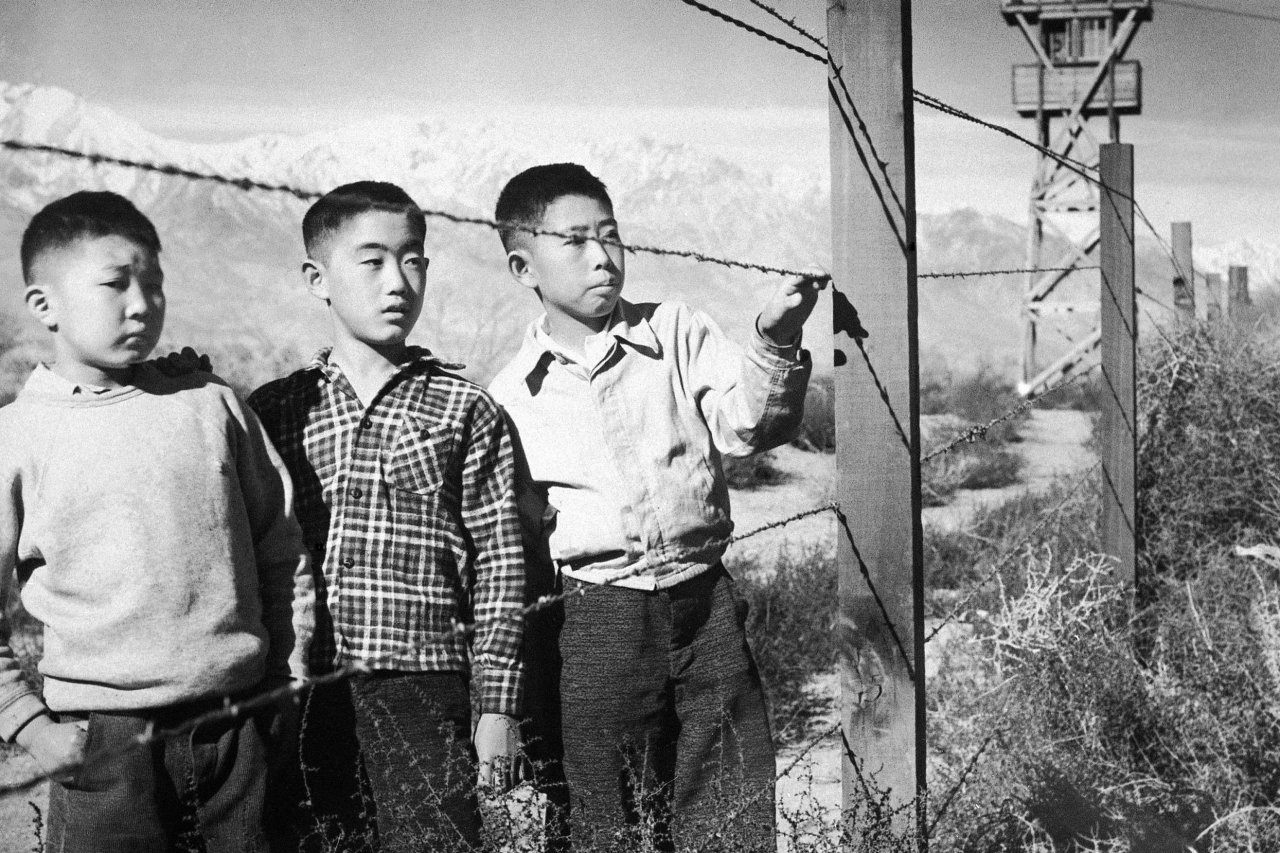

Manzanar is on swath of high desert behind which rise the Sierra Nevada. The wooden guard tower planted in the desert floor looms like an emaciated giant against its immediate surroundings, but it is minuscule against the mountains in the background, covered in fresh snow. Manzana is Spanish for apple, and there were apple orchards here once. The Japanese prisoners, who were kept at Manzanar for three years, planted their own as well. You can see them on the edge of the camp, dry branches reaching into blue sky.

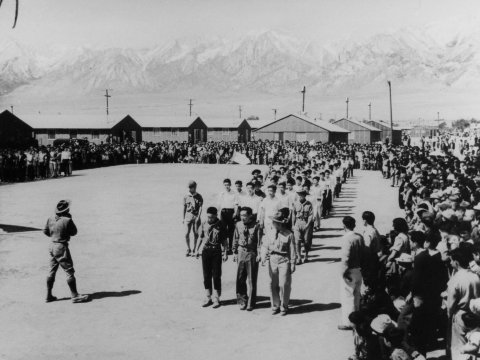

The camp consists of an excellent series of exhibitions inside the repurposed, barnlike auditorium, which the Japanese prisoners built. Behind the auditorium stand a handful of the 504 barracks where 11,070 people spent World War II. From the outside, the barracks look sort of like those at Auschwitz: low, squat buildings. And the wooden guard tower at the edge of the camp reminded me of Guantánamo Bay, which I had visited for a reporting story a few years before.

Manzanar was not a concentration camp or a jail, though what it was is hard to say—"internment camp" doesn't quite convey the injustice of confining American citizens without due process. In some ways, life inside Manzanar was shockingly ordinary. Children went to school and acted in cowboys-and-Indians play; adults danced to the tunes of a jazz band named, cheekily, the Jive Bombers. There weren't gas chambers, of course, and the military police who patrolled the barbed wire fencing didn't venture inside Manzanar, giving those inside a measure of autonomy your average Gitmo detainee could never dream of. Yet the ordinariness was circumscribed by an extraordinary abrogation of civil rights.

Also, most of the Japanese-Americans at Manzanar came from Los Angeles or some other relatively urban West Coast settlement. They had no business in the desert, an alien landscape that became part of their punishment.

"There was always the wind," one Japanese-American confined there remembered later. "There was always the wind."

A fear of espionage was the reason given for Japanese internment, just as a fear of terrorism is the reason Trump cites for his travel ban. But there were no spies among the Japanese confined during World War II. And there has never been a terrorist attack committed by a refugee on American soil.

The obvious lesson of Manzanar is that erring on the side of fear never gets us to that "shining city on a hill" Reagan evoked as he left the White House in 1989.

Yet some disagree, even as they stand in this high desert history classroom. Greg and his wife have come up from Camarillo, in Southern California. "I don't think it was actually the wrong thing to do at the time, given what they knew," Greg says of Manzanar.

He supports Trump's immigration ban: "We have no way of vetting them, so why should we be letting them in?" He makes the point that while the Japanese-Americans confined at Manzanar were American citizens, the people affected by Trump's immigration order are not and are therefore not entitled to constitutional protections.

During the presidential campaign, Trump called Syrian refugees a "Trojan horse," implying that terrorists lurked among them. Most refugees, in fact, are women and children.

The image, however, comes from FDR. He used it during one of his "fireside chats," in 1940, to warn "a nation unprepared for treachery" and thus ripe for exploitation by "spies, saboteurs and traitors." He invoked, as counterargument, the strength of the American project, to which "the blood and genius of all the peoples of the world" had contributed.

"We have built well," Roosevelt concluded.

Twitter helped elect Trump, but it's also the site of strong anti-Trump sentiment. There was, for example, the brave soul who manned the Twitter account at Badlands National Park and, on January 24, sent out several tweets with statistics about our rapidly warming planet.

The Trump administration doesn't believe in climate change, so some White House martinet ordered the Badlands account to go silent. That, of course, propelled those climate-change tweets into hypervirality. Others started parsing the multitude of National Park Service–related accounts for signs of anti-Trump resistance.

One of the tweets cited for its subtle anti-Trump bent was by the Death Valley National Park account, which sent out this missive on January 25: "During WWII Death Valley hosted 65 endangered internees after the #Manzanar Riot." Most people—myself included—knew nothing about the Manzanar Riot but understood that the tweet was about the powerful protecting the vulnerable.

As I found during my visit to Manzanar, the reference is to a conflict that broke out in 1942, between political factions in the camp that were divided over how much to collaborate with their American captors. The disorder was quelled by the military police, who killed two inmates. As the Death Valley tweet indicated, some of the internees were taken to Death Valley and sequestered there for their own safety in a Civilian Conservation Corps campsite called Cow Creek.

The liberal policy site Mic branded the tweet an "apparent act of defiance."

Manzanar does not tweet, and its rangers studiously avoid politics. But they are also obviously aware of what the camp means today, even if they aren't allowed to discuss the obvious parallels. Ranger Rosemary Masters led me on a tour of the camp. Manzanar, she told me, "is a perfect example of what happens when we don't pay attention to the United States Constitution."

Politics seeps in in other ways. The day I visited, a whiteboard celebrated Fred Korematsu, a native of Oakland, California, who tried to avoid internment by hiding but was discovered after three weeks, arrested and imprisoned. California marks Fred Korematsu Day on January 30, which fell this year just three days after Trump signed his immigration order. Google, returning ever so briefly to its idealistic don't-be-evil roots, made Korematsu the subject of a Google Doodle.

Korematsu's conviction was vacated in 1983. The whiteboard in Manzanar quoted from that decision: "In times of distress, the shield of military necessity and national security must not be used to protect governmental actions from close scrutiny and accountability."

Manzanar broke its attendance record last year. Masters told me the spike might have to do with a prolific wildflower bloom in nearby Death Valley. A broader upward trajectory, she speculates, might also have to do with the 1998 mandate that all students in California's public schools learn about the internment of Japanese-Americans. Children see the highway signs for Manzanar, she told me, and plead with their parents to stop.

The people who have come on a Tuesday morning in the middle of winter seem to be acutely aware that Manzanar has an even more ominous significance today than it did on November 7, 2016. Now you come here and pretend that this was long-ago ugliness we'd never replicate.

A well-dressed photographer from Los Angeles told me he'd been taking pictures in the mountains but decided he had to come down and see Manzanar because of all the insanity happening in Washington. As we stood in the former mess hall, next to a trapdoor where a cache of sake was once hidden, the photographer marveled at how quickly Trump had moved to accomplish his most extreme campaign promises. If we had a travel ban after two weeks of a Trump administration, how long before we'll have our very own Manzanar, not to mention our own Hiroshima?

Two people cried when I asked about Manzanar. One was a young woman whose children ran through the exhibits as we spoke. Her grandfather had been in an internment camp in Arizona. The family was driving back from Mammoth Lakes when she said, "We need to stop here." Through tears, she called Trump's immigration ban "gnarly." The word, when she said it, had none of its usual laid-back connotation.

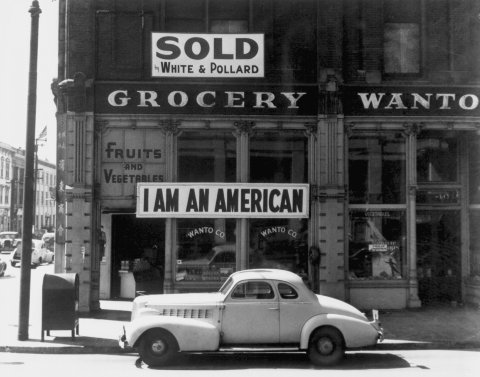

Carol Garner also cried. She, her husband and three children were from San Diego. They'd also been visiting Mammoth Lakes and heard about Manzanar from a friend. Now they were standing in a barracks that featured an exhibit about "Question 28" on a federal survey given to all interned Japanese by the federal government. The question asked if the respondent was loyal to the United States and would "forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor." Since most of the Japanese were American citizens, they found the question odd, even insulting. Even though answering in the negative could mean deportation to Japan, some did anyway. Explained one internee quoted in the exhibit, "I said 'no' and I'm going to stick to 'no.' My wife and I lost $10,000 in that evacuation.… That's not the American way."

Garner is Chinese-American, and she told me that growing up, she was frequently told to "go home," though she'd never had a home other than the United States.

"He's making choices based on fear," she said of Trump's immigration ban, "not based on facts. And that's pretty much when racism goes rampant." You see it on Twitter today, with Pepe the Frog memes; you saw it during World War II, when Japanese-Americans were widely regarded as spies. "The Japs Must Not Come Back," says one pamphlet exhibited at Manzanar. Next to it is a newspaper excerpt about Wilma Insigne of Walnut Grove, California, who was arrested for threatening to burn down the home of a Japanese family. The family was that of Private Yoshio Matsuoka, "a war veteran who just returned to the United States after spending 10 months in a German prison camp."

Not everyone, though, was troubled by Manzanar's present-day implications. Richard Yung came here from Oakland. An immigrant from China, he wandered through Manzanar in one of those fashionable German military jackets. He seemed to like Trump's call for "extreme vetting" and rejected the alarmism coming from protesters at airport terminals. "He hasn't put people in camps yet. Maybe he will."

To really see Manzanar, you have to use your imagination. Most of the barracks are gone, leaving behind an expanse of sagebrush and sand. It's hard to tell if the debris—twisted scraps of steel, rusted cans—are historical relics or just litter. There are at least 30 intricate rock gardens, testament to the desire of those imprisoned here to re-create a fragment of their culture. There were churches, a judo dojo, a hospital and a baseball field, but these are all gone. As impressive as Manzanar National Historic Site is, what actually remains of the camp is not much—it is history effaced.

It is also history displaced. In the four years that followed the end of World War II, the War Assets Administration sold off the barracks of Manzanar, in part as veteran housing. At $300 per barrack, this was a good deal, as long as you didn't mind inhabiting the former quarters of war prisoners.

Today, many of the barracks remain around Inyo County. Several have become part of the Lone Pine Budget Inn, a one-story mustard affair by the side of the highway. For about $60 a night, you can sleep with the ghosts of Manzanar. I tried to find out if the motel's proprietors were aware of this legacy, but nobody answered my knocks at the front office: Many motels in the Eastern Sierra shut down in winter. I spied a sign inside: "We no longer have HBO."

Another barrack became part of a Catholic church in Independence. I saw no sign indicating the provenance of the wood for what was now known as Zegwaard Hall. There was, however, a marble plaque outside the main building of the church, but it had nothing to do with Japanese internment. It read: "In loving memory of all unborn children, victims of abortion."

Alisa Lynch, chief of interpretation at Manzanar, told me this: You cannot make people remember, and you cannot make people remember in the way you do. You can only show them what was. They will draw their own conclusions, which no exhibit or display can predict.

Some Inyo old-timers still call Manzanar what it was called during World War II: "Jap Camp."

Inside the work office used by rangers at Manzanar, Masters left me with the guest books from 2016, huge volumes signed by visitors to the camp. Many notes left by guests from early 2016 have a pretty familiar, and unsurprising, this-can't-happen-again sentiment, but as the presidential election neared, and the possibility of a Trump victory became real, a darker tone emerged.

A visitor from 2016: "I see the writing on the wall."

This was by a tourist from Los Angeles: "Remember, this was all created by executive order. We need to be vigilant."

Humor works too: "We have the best camps. The biggest ever. But people don't appreciate. SAD."

Later, Lynch sent me a testimonial left on October 30, 2015: "I have been prejudiced all my life against Japanese (75 years). As of today that is gone. I am so ashamed. I cry as I write this. Thank you."

There is a gift shop; there must always be a gift shop. The one at Manzanar is quite good, and you feel even better knowing that your vintage travel poster, rendered into a fridge magnet, is going to support the National Park Service, which isn't likely to see a funding windfall from the Trump administration.

Next to the cash register is a display case with pocket-sized copies of the U.S. Constitution. "This summer, it sold really well," Lynch says with an impressive lack of affect to her voice. A consummate professional, she will not talk politics, so it is fruitless to ask her whether that's because Khizr Khan, a Gold Star father who lost his son in Iraq, held up that same edition of the Constitution at the Democratic National Convention and asked then-nominee Donald Trump, "Have you even read the U.S. Constitution? I will gladly lend you my copy."

There are also copies of Farewell to Manzanar, by Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James Houston. A native of Los Angeles, Wakatsuki was sent to Manzanar when she was 7 years old. She writes of the "sandy congestion and wind-blown boredom" she witnessed upon arriving at the camp, describing in detail the discontent that led to the Manzanar Riot. A frequent presence on school curricula, Farewell to Manzanar has gone through more than 60 printings and sold over a million copies. Yet the University of Illinois also includes it on a list of young adult books that have been challenged for alleged improprieties that might sully the minds of patriotic, freedom-loving American schoolchildren.

I'm going to guess that "Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians" is not among the more popular items in the gift store. Published in 1983, it spends 493 pages on the two questions most worth asking of history: Why? And how?

Among the many conclusions it makes, the report notes that there was a widespread belief in the early decades of the 20th century "that the ethnic Japanese would not or could not assimilate to 'American' life and represented an alien threat to the dominant white society."

The report declares that internment was a mistake:

In sum, Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity…. The broad historical causes that shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership. Widespread ignorance about Americans of Japanese descent contributed to a policy conceived in haste and executed in an atmosphere of fear and anger at Japan.

I genuinely believe that if people took the time to read the reports written by government commissions about the varieties of human evil, error and depredation, the prospects for our civilization would be vastly improved. I know, however, that it is hopeless to wish for a world in which people earnestly read government reports.

I leave Manzanar and begin the long drive over the mountains. Sprint reception is horrible in Inyo County, and FM radio reception isn't much better, so I listen to my Reagan book, which has the Gipper abandoning the liberalism of his younger years for a strident, anti-Soviet, pro-corporate conservatism.

In South Lake Tahoe, there's finally service again. I have emerged from the internment camp into a gaudy, glimmering strip of Americana. As I fill up my rental car, I scroll through Twitter. This is a gut punch of an experience, my feed full of heartbreaking pictures of children in Syria who thought they were about to become Americans. They will remain refugees while we restore ourselves to greatness.

Manzanar had its own newspaper, the Manzanar Free Press. You can buy replica editions at the gift store. I bought three. It is like an ordinary newspaper, but there's a kind of clenched cheer to all the articles—which were published without bylines—that you suspect was the product of official censorship or at least official pressure.

This is from the September 10, 1943, edition of the Manzanar Free Press: "After all this is over, when Manzanar is nothing more than a dim memory in the cycle of one's life, the High Sierras will be remembered with fond dreams and not with cynicism or bitterness."

This did not come to pass. Manzanar did not recede in our collective memories. Nor was it burnished by time into something not entirely unpleasant, like one's middle school years. Manzanar is still Manzanar, and it is still with us, even as the creosote crawls over the remnants of the camp, and the winds come off the mountains, stirring up sand, and cars rush past on the highway en route to more glamorous destinations, like Mammoth Lakes. It doesn't matter. Manzanar will remain; Manzanar will not allow us to forget.