Marc Maron is telling me about his New York City day. He lived here, on and off, for nearly 30 years, before settling in Los Angeles in 2009, where he hosts his podcast, WTF With Marc Maron, out of his garage. Back in the city briefly, to do press for the Netflix series GLOW, he indulged in some local favorites: the Whitney Museum; an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting in the West Village—one of the first he attended 20 years ago; a slice of pizza at Joe's on Carmine Street; and lox and bagels at Russ & Daughters, where he jotted down an idea for a new bit.

"As a Jew, sometimes you just spend the day smelling like fish and onions," he says, offering one of the grins—almost a grimace—that punctuates his funny observation. "It's part of our history. It's part of our culture. Some days, we're just going to smell like fish and onions."

Does he feel more Jewy in New York? "Sure, definitely," he says, and he misses the city, but he doesn't want to live here anymore. L.A. traffic drives him nuts ("It makes you not want to go anywhere"), but he loves living in a house. "So you build a life where you live.…You have to love your house. That's a rare possibility in New York. The idea of loving your apartment? Back when I lived here, you wanted to spend as much time as possible away from it."

We've met in the restaurant of the Ludlow Hotel, on the quickly gentrifying Lower East Side. He points through the window, across the road, to another hotel: "That's where the Luna Lounge used to be." Between 1995 and 2005, the bar's legendary back room became a sanctuary for fans of indie rock (the Strokes and Interpol played their first shows there) and alternative comedy. For eight bucks every Monday, you could catch the likes of Maron, Janeane Garofalo, Sarah Silverman, Patton Oswalt, Louis C.K. or Dave Chappelle. "I spent a lot of time on this street," says Maron, "hanging around, going to the Hat [a late-night Mexican restaurant, actually El Sombrero]." He grins. "Yeah, drunky me, running around and sweating."

There was a little Sam Sylvia in Maron back then. Sam is the washed-up, coke-snorting, B-movie director that Maron plays on the comedy GLOW, which made its critically acclaimed debut last year and is returning for Season 2 on June 29. The comedy series, created by Liz Flahive and Carly Mensch, is set in 1985 and co-stars Alison Brie and Betty Gilpin as two of 14 struggling actresses attempting to create the first-ever TV show about female wrestlers—loosely based on a real '80s novelty series, GLOW: Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling.

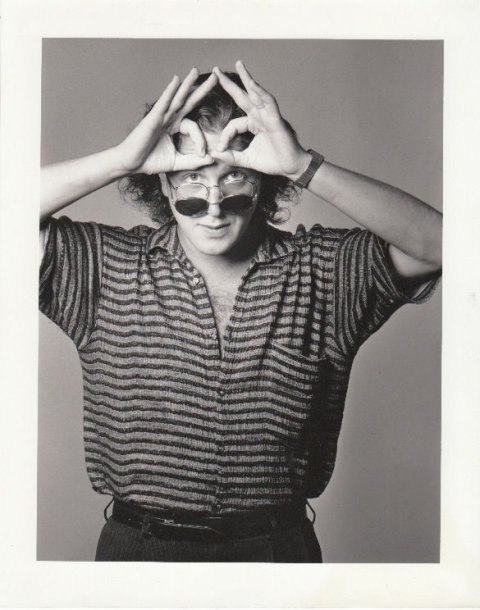

For the women, it's big hair and spandex. For Sam, it's all about the mustache, a Tom Selleck–style soup strainer that's shorthand for sleaze. When Maron read the script, he loved the part so much, he bought himself some aviator sunglasses, put on a polo and filmed a scene with his female trainer (standing in for Brie) on his iPhone. "So I guess I was the guy," he says.

"You could instantly see all these different sides of Sam," says Mensch, who hadn't considered casting the comedian before she saw his audition. "The humor, the drug addiction, the swagger, the disappointments. It also helped that he found these aviator glasses that kind of instantly transformed him from Marc Maron."

"We had always wanted to tell the story of a misogynist dropped into the middle of 14 women and how that changes him," adds Flahive.

Sam is, to put it bluntly, a dick. And Maron plays the part supremely well. This is his first mainstream role, so for many viewers he's a revelation. But the performance is an eye-opener for fans, too, since his only other leading role was playing a version of himself—a twice-divorced recovering addict and podcast host on the IFC show Maron. He's good enough that, earlier this year, he was nominated for three awards, two from the Screen Actors Guild and one Critics' Choice Award. "I didn't expect to win," says Maron, and he didn't, "but Frances McDormand came up to me at the SAG ceremony and said, 'I love you on that show. We all knew that guy.' That's kind of winning."

Maron's facial hair is back to normal today, which means more beard and a hipster soul patch. He's looking like the star of his two Netflix comedy specials, including last year's Marc Maron: Too Real, which includes arguably the funniest bit about Mick Jagger on record. He was never a huge stand-up guy—more of a cult favorite. GLOW has provided the 54-year-old with not only the best reviews of his career but, thanks to a cast and crew that is 90 percent women, entrée into a world beyond comedy's traditional boy's club. "Seeing their process and seeing what they're going through, both on screen and off, that's a revelation," he says of the actors and writers. "To not be the center of attention, or strutting around, is new to me. GLOW is about them, really. It's not about me. I'm very aware of that, not only in the workplace but on screen. This is a woman's show, and I respect that."

To play "a shameless, unapologetic bully," Maron drew on his own "dark years," struggling to make it as a comedian. "Sam thinks he's bigger than he is, or thinks that it's only a matter of time before somebody understands his genius," says Maron. "For me, having been somewhat of a puppet of my own ego, in a relatively destructive way, I get that. I was never in Sam's position of leadership, of having power," he adds. "But I've been a shit in relationships. I would say Sam is half me."

Helpfully, too, Maron is not writing the show, which allows him to "turn off my own neurosis and focus on Sam's. I'm self-aware at this point, and the fact that he isn't enabled me to look like I was acting. "

Maron used to do a joke about making it. "They say it takes 10 years to create an overnight success, but that's the exact same amount of time to create a bitter failure. You're not sure what it's going to be until the night before." For him, it took 20 years.

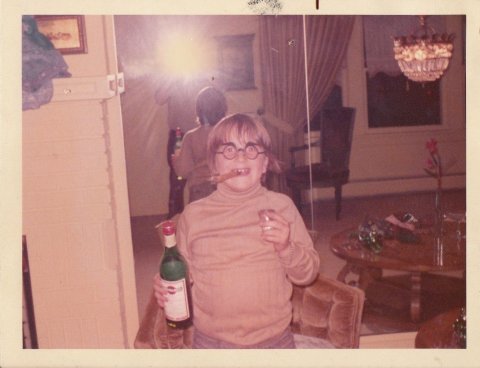

He was born in Jersey City, New Jersey, and grew up in Albuquerque, New Mexico, a funny kid who, as he explains it, wasn't all that funny as a stand-up comic, at least at the start. Maron, smooth-tongued and fast-talking, can slip into pop-psych sound bites. "For years," he says, "intensity, defensiveness and hostility was like a shield, obfuscating my natural sense of humor and timing."

He's described and analyzed his drug- and alcohol-fueled early days in his stand-up and on WTF, and yet it's hard to imagine how this naturally wired guy—currently insatiably consuming grilled oysters and large hunks of bread—could possibly need additional stimulation. A lot of it had to do with fear. "That didn't leave me until about five years ago," says Maron. "Most of your career, you pretend you don't have it."

It was the podcast, started in 2009, that changed everything. WTF has become one of the most popular shows in a fast-growing entertainment market, getting 6 million downloads a month, with over 410 million lifetime downloads. It was what helped him land his IFC show, which lasted for four seasons, until 2016, and it has certainly raised his profile as a stand-up comic.

After years of financial uncertainty, "me and my producer, Brendan McDonald, do very well," says Maron. "It's nice to want to do something, like GLOW, to seek out opportunities without it being life or death." (When I congratulate him on the recent sale of his Highland Park home, for $920,000—nearly triple what he paid for it—he seems vaguely embarrassed. "It was a crazy amount for a less than 1,000-square-foot house with one bathroom," he says, "but what was I supposed to say? 'That seems unfair and unreasonable! I want to give this house away!'")

The podcast was an extension of what Maron had done for Air America, the liberal talk radio network that went bankrupt in 2010. "I took that first job in 2004 because I didn't have much going on, and it seemed like an opportunity," says Maron, who was also getting financially leveled by a second divorce; he needed the money. He ended up doing three shows (he was fired all three times, then rehired twice), the most popular being Morning Sedition. "I wasn't a political junkie, but I was a reactionary guy. I was definitely ready to fight the power. But I'd never done a radio show."

It quickly became a passion. Maron loved the immediacy of live radio. He also had a talent for it. "Once I learned how to man a mic on my own for hours without anybody there, it was pretty free sailing."

Along the way, he'd noticed a new streaming version of radio, and after he got the final ax from Air America, he and MacDonald looked into podcasts. Things were even direr financially. "I was down for the count," says Maron. "I didn't know if I could find a way out. The podcast wasn't a way out," he adds, "it was just that I needed to keep doing something." Maron and a community of pioneers "all learned together, supported each other. And then, all of a sudden, the medium started to grow, and networks and advertising platforms emerged."

Maron's humor was always heady, observational and slightly neurotic. (Not in the sense of "Oh, I can't go outside," he says in a Seinfeld whine. "I just overthink everything.") From the beginning, he used stand-up as a way to explore personal stuff. "Whatever emotional growth I've been going through, over any of the time I've been working, that's going to show up in my stand-up," he says. "It's not a caricature—I was never doing a character."

That remains true today, but with the podcast he isn't just doing bits about emotional growth; it's allowing him to publicly hash things out via monologues and conversations with guests. And it's given him an audience that knows him in pretty deep ways "because it doesn't require me to be funny," says Maron, whose listeners get regular updates on his equally jumpy rescue cats, Monkey, LaFonda and Buster Kitten (he calls his home the Cat Ranch). "Creating something that resonates with people, that your heart is in—it's an esteemable thing. After 20 years of hits and misses, it has an effect on somebody—and not a bad effect."

The uptick in self-esteem has spilled into his stand-up. "It finally got me back to whatever me funny as a younger person was, as opposed to being some disruptive, aggravated weirdo. I have a much easier banter, and I don't fear being onstage."

The podcasts, of which there are more than 900, run an hour or more. The bulk of that time is spent talking with a guest—mostly actors and fellow comics. Perhaps because he's spent so much time sharing his own demons, Maron is adept at getting others to do the same. In August 2016, well before Roseanne Barr screwed the revival of her ABC show with a racist tweet, she and Maron talked about her mental illness; a 2010 interview with Robin Williams, one of the most popular WTF episodes, revealed Williams's struggles with depression, years before he took his life in 2014. Listen to them now for poignant context.

On June 19, 2015, President Barack Obama showed up in Maron's 165-square-foot garage for an interview—two days after Dylann Roof killed nine people in the Charleston, South Carolina, church massacre. It's hard listening now, not only because mass shootings and gun violence have increased, but because of Obama's lack of cynicism; after 18 months of President Donald Trump bellowing about "American carnage," political witch hunts and "animals" streaming across the border, Obama's hope and positivity about America are kind of mind-blowing. "I know a lot of people have listened to it again now," says Maron. "It's really sad. But I'm glad it's out there."

Would he be interested in interviewing Trump? "I'd be nervous," he says. "He's a weirdly manipulative and threatening presence, but also very disarming in his own dumb way. He'll prop you up. He'll sweep you up. So the challenge would be to do what I do and get at the guy. Would it be possible? What's in there?" A tricky task that Maron would welcome, if only to make Trump "genuinely defensive."

The first season of GLOW introduced the motley crew of women, each of whom adopts a wrestling personae: a welfare mother, a Middle Eastern terrorist, twin grandmothers, a she wolf. Sam reluctantly agrees to direct the show because he's hoping the producer—a dopey rich kid named Bash—will finance his film, a last shot at mainstream success. The aggressively peppy, hyper-organized Ruth, played by Brie, and former daytime star Debbie, played by Gilpin, are friends who fell out over Ruth's affair with Betty's husband. Over the course of the first 10 episodes, Sam and Ruth form a sort-of partnership (grudging in his case), and in one of the show's more unexpected moments, he accompanies her for an abortion.

"For a comedy, GLOW deals with some pretty heavy shit," says Maron. But what makes the show joyful and, at times, transcendent, is the focus on the common goals of these young women who want to "define and empower themselves through this spectacle and craft," he says. "Also, the writing is brilliant."

The real GLOW was low-budget, over-the-top comedy sketches, but the tone was raw—at times disconcertingly so—and the women rough. "There's a hint of tragedy to it," says Maron. The Netflix characters are more earnest and endearing, the situations quirky rather than desperate. And Ruth and Sam's "sort of spiritual alignment becomes a sweet thing," he says, "particularly since it's not sexualized in any way."

So it's a shock to see Sam back to bullying Ruth in the first two episodes of Season 2. Sam has a lot on his plate: He has discovered he has a teenage daughter from a one-night stand (now living with him), and in the Season 1 finale, he learned that the film Back to the Future had hijacked his movie idea, thus negating the only reason he'd signed on for GLOW. "Sam's cynicism and natural defensiveness—and an assumption that he's in control, when he's not really—that becomes even more threatened this season," says Maron.

The show debuted several months before the Harvey Weinstein allegations, but Sam is, in many ways, the poster boy for male abuses of power. "I don't know if it's in direct response to #MeToo, but the show addresses it in a weird way in Season 2," says Maron. "There is a transgression that happens, with one of the women, and I react to it in a way that my character would have reacted to it. Sam is a guy of his time, and the idea of abusive power on those levels didn't exist in 1985. It was just the way it was."

And because the show is true to the times, Sam will not radically change, but he will evolve, says Flahive: "He isn't insulting the women as much this season, maybe even caring about some of them. He kinda wakes up and realizes that this show might be his shot." In other words, says Maron, "he's a redeemable dick."

The third most popular WTF episode (after Obama and Lorne Michaels) is Maron's two-part October 2016 conversation with Louis C.K. The two met on the Boston comedy circuit in the early '90s but had fallen out—largely, Maron explains, because of his own bitterness and jealousy over C.K.'s meteoric rise. In a shades-of-Barbara-Walters moment, Maron gets C.K. to cry over their broken friendship. "I was so consumed with my own self-hatred and anger that I just couldn't see past anything," Maron says now.

Since the podcast is Maron's place to unpack his thoughts, he did just that after The New York Times broke the allegations against C.K. last November. In a candid monologue before an interview with indie rocker Kim Deal, he reckoned with his friend's "gross" and indefensible conduct, as well as his own, and the prevailing environment of gender disparity in comedy and the world at large. "You know, when you have a man brain," Maron says at one point, "you are not capable of empathizing with women."

He talked about the lack of diversity on his IFC show (which had zero female writers) and his own toxicity: "I think I may be at 25 to 30 percent level now, but I've certainly been around 90 in terms of being emotionally abusive, insensitive, angry and selfish." And he revealed a story that led to his own empathy for victims of unwanted sexual attention: A kiss on the mouth from a drunken male professor—a "powerful, impactful guy"—whose approval Maron desperately wanted. He was 18 at the time, and he described the paralysis and shame he felt afterward.

The C.K. news changed him, Maron says now. "I had to search my soul, calling myself out about what is flirtation, what is necessary engagement or attention paid. Not necessarily assault, but inappropriately aggressive behavior, emotionally or sexually," he says. "And there's a lot of micro about that."

An old girlfriend once gave him perspective that he repeats now. "She used to tend bar at a strip club, and eventually she quit," he says. "I asked why, and she said, 'I got tired of men looking at me like I was food.' You forget that the male gaze is a real thing. We all have it, and it's something that has to be managed."

In his C.K. reaction, Maron made it clear that he was not ending his friendship with C.K. "He's in big fucking trouble. So what am I gonna do?... It's probably the best time to be his friend, when he needs to make changes…. I can learn from it. He can learn from it."

HBO, Netflix and FX quickly cut ties with the disgraced comic, and HBO removed his work from its platform. "That was scary," Maron says, "because that's the marketplace responding, and that's people's livelihoods. That's also what an artist has given the world."

Maron questions blanket treatment of transgressors. "The idea of censorship or reactionary revisionism or erasure, that's like…stuff has to be navigated," he says. "There's gotta be dialogue and a process for people who don't commit a crime. Taking responsibility is one thing, but does everyone deserve to be destroyed forever, for anything transgressive?"

His self-searching continues, twice a week, on his podcast and in his stand-up, which takes him around the world. When he's not on the road, he tries to do a couple of 15-minute sets a week at the Comedy Store on Sunset Boulevard, where he started his career in 1987 at 24. He's a fan of Ali Wong, Iliza Shlesinger, Whitney Cummings, Seth Rogen, Kevin Christy. "David Spade's been coming around and Yakov [Smirnoff]'s back," he says of longtime friends. "The Store guys."

A question about comedy trends makes him wince. "Trends?" he says dismissively. You know, emerging, groundbreaking stuff. "If anything, comedy is less adventurous," says Maron. "It used to be, on an off-night at a comedy club, you'd see guys push the envelope, cut loose, snap onstage, do weird characters—you'd see all kinds of rude shit back in the day. But now, with social media and cellphone cameras, there's a premium on not looking stupid. It's stifling."

When I say that the tables have turned, that he's now where pre-disgrace, big-time C.K. was, he dismisses the suggestion. "I don't sell out Madison Square Garden, but I do a lot of things, and I'm personally invested, and I'm not hiding much."

For him, that—along with the bigger garage/recording studio in his new house—is enough. "A lot of the things I thought wouldn't have happened for me have happened, in a scale that is different than I would have imagined," he says. "It's all been a little off to the side from mainstream show business—with the IFC show, the podcast, my stand-up. I have a good following. I'm not huge. I'm not Kanye. I'm not Louis. I'm just right."