The young Marine's mother rehearses the medical timeline in her mind, over and over.

"He dies every day...I'm just replaying the build-up," Lynda Kiernan, 50, told Newsweek in January. "I know exactly what happened each day, building up to February 5th, so I know what Beck was going through today, and I know what he will be going through tomorrow."

"I know how he was suffering, I know how god-awful sick he was, and how alone he was, and I know how he was still pushing and what February 1st means and what February 2nd means and 4th...and it's really hard."

One year ago this month, on February 5, 2018, Private First Class W. Becket Kiernan, a newly minted U.S. Marine training to become a field radio operator, died at Desert Regional Medical Center in Palm Springs, California, an hour and 10-minute drive south of the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center at Twentynine Palms.

A Newsweek investigation over the past seven months obtained official Defense Department memos and letters; examined detailed medical notes; and interviewed both current and former U.S. military sources stationed at the Marine base at Twentynine Palms to reconstruct the last days and hours of Becket Kiernan's life. Newsweek attempted to contact those mentioned by name in this story.

The reporting underscores medical privacy violations; medical facilities that are understaffed to handle the volume of U.S. service members; and a botched process of how the U.S. military informs parents about the death of a child.

And while this Marine died from a hard-to-diagnosis flesh-eating bacteria disease, his story reveals institutional failures within the U.S. Marine Corps and Navy medicine, and his mother's determination not to let his death be in vain.

A Personal Calling

W. Becket Kiernan was born and bred to be a U.S. Marine.

It was something about their swagger. Those crisp dress blue uniforms with gold emblems and red blood stripes running down the side pants leg that made it seem like only God himself could create such a warrior. But beyond the superficial appearance of immaculate uniforms and military bearing, the calling was deeper—one of honor and obligation to service.

At the age of 10, Becket joined the Young Marines association, first at Old Colony in Plymouth, Massachusetts and later in Fall River. The Young Marines are a non-profit organization founded in 1959 to promote character building and leadership for boys and girls, ages eight to 18. The program is run by former U.S. Marines or other retired U.S. service members and volunteers.

Becket would distinguish himself from his peers and obtain the rank of Young Marines sergeant major, the highest rank attainable in the organization. At Christmas, he organized the Young Marines' Toys For Tots program, delivering gifts to disadvantaged children.

Growing up, Becket was a scholar-warrior and an avid reader of military history, spending his time dissecting the teachings of Sun Tzu's The Art of War.

Becket enlisted in the Marines and shipped out for Parris Island, South Carolina, on September 5, 2017. He graduated from boot camp in November and would then undergo a condensed version of basic infantry training in North Carolina.

After graduating on January 23, 2018, Becket flew cross-country to report to the Marine Corps Communications-Electronics School in California, the largest training school in the corps, located at the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center in Twentynine Palms.

But just days after Becket reported for duty, he became ill and said his right hip and leg were excruciatingly painful. Around January 30, he walked to the Adult Medical Care Clinic (AMCC), which provides primary care to active duty service members, but he was turned away. A review of Becket's medical file shows no record of him seeking treatment at AMCC.

Becket told his mother he was turned away because Navy medical professionals believed he was malingering.

Both Marines and Navy corpsmen interviewed for this story said some service members try to embellish their symptoms to avoid physical or field training, and sometimes Marines are sent away without being medically screened during sick call visits because of those cases. Marine leaders sometimes discourage service members from seeking medical treatment, encouraging a "suck it up" mentality.

Newsweek sought to interview Major Devlin O'Shea, Becket's company commander, about AMCC, but Marine Corps Combat Development Command (MCCDC) declined the request.

In the Marine Corps, company-size ranges between 150 to 200 individuals, but for Company B, Becket's unit at the Communications-Electronics School, roughly 1,500 were assigned — the equivalent of roughly five companies or what makes up a battalion.

Former First Sergeant Frank Becker, the senior enlisted adviser for Becket's company and O'Shea's right-hand man, worked at the school from September 2016 till his retirement, said they had a list of issues with the inadequate or nonexistent medical care their Marines received, and because of the abundance of students—neither AMCC or Robert E. Bush Naval Hospital was equipped to provide quality care.

"We expect medical to take care of us, and 1,500 Marines is a lot," Becker told Newsweek by phone. "[Becket] was just one kid that had issues with medical; there were a whole lot of other medical issues that did not get checked [by AMCC or Bush Naval]."

The grievances Becker outlined range from long wait times at Bush Naval Hospital to Marines with medical issues being sent away without being seen by a provider.

Among the most egregious offenses, he alleged, was the divulging of private medical details in public spaces, a violation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) and other patient privacy regulations.

"I had Marine instructors go to medical and then Doc would come out and yell, something like, 'Flores! Genital Warts, where you at?' You know, announcing their business to everybody, so I told my CO [commanding officer] about that crap, and that was one of the things that were brought up," Becker explained.

For lower ranked Marines, obtaining a medical appointment was sometimes a problem.

Becker said he would have to escort his Marines back to AMCC after they had been sent away to get them an appointment. A former staff noncommissioned officer told Newsweek that a staff sergeant they knew had a hard time getting care for a foot injury, despite his elevated rank this past January.

Marines needing mental health treatment had to be transported to Naval Medical Center San Diego, which is more than a four-hour drive from Twentynine Palms, said Becker.

"There's a laundry list of daggone problems [with medical services] that my commanders, my company, my instructors and even myself and CO [commanding officer] have seen," Becker said.

Company B leadership told Lieutenant Colonel Barian A. Woodward, former commander of Communication Training Battalion who is now a fellow at the U.S. Institute of Peace, and Colonel Dom D. Ford, head of the Communications-Electronics School, about their Marines not receiving the medical care they needed.

Ford was engaged in ongoing conversations with Navy Captain Nadjmeh M. Hariri, the commanding officer of Bush Naval Hospital, about improving the care Marines received at the school, said Becker. Newsweek does not know the content of those conversations or what improvements, if any, resulted from them.

Ford said he is always working to improve conditions for his Marines, but that those conversations should not be interpreted as maligning the medical care at Twentynine Palms.

A former U.S. Marine staff noncommissioned officer and a U.S. Navy officer both confirmed the multiple medical issues laid out by Becker at AMCC and Bush Naval Hospital, and said some of those issues continued today.

'Please Tell Him I'm Coming'

Three days before February 5, Becket was removed from classroom training by ambulance and taken to Robert E. Bush Naval Hospital at Robert E. Bush Naval Hospital at Twentynine Palms, because his skin was turning blue and he had severe pain in his hip and leg.

Becket was displaying "flu-like symptoms," with a fever of 101.2.

A flu test came back negative, but he was "tachycardic," the medical term for having a rapid heart rate.

He was given fluids and Tylenol that "seemed to help him," according to medical notes. Becket was discharged from the hospital with Motrin, and a flu diagnosis, despite the negative flu test.

He was placed on two days of SIQ, a military acronym for "sick in quarters," a status used by medical professionals to prescribe bed rest to service members when the medical condition or injury is not severe enough to warrant inpatient care.

Under the rules of SIQ, Becket was confined to his barracks room, and dependent on others for care.

Over the next two days, Becket lay in agony in his room. Neither the Marines on duty in the barracks nor leadership from his chain of command checked in on him during this time. The responsibility was left to Becket's roommates—Kiernan believes the task should have fallen to Marine leaders.

The Marine Corps said Becket's instructors told his roommates to look after him over the weekend while he was SIQ. Kiernan told Newsweek that the naval hospital told Becket to have his roommates look after him.

In a memorandum obtained by Newsweek issued three months after Becket died, Major O'Shea, at the time a captain, made it company policy that any Marine on SIQ could not go more than three or four hours without a wellness check—a practice seen in other units and training commands around the corps and years before February 2018.

Before February 2 and after, Becket would give his roommates money to purchase Tylenol, Gatorade, and a bit of food from the base exchange because it was too painful for him to walk, and now on SIQ, he was not allowed to leave his room.

One day while on bed rest, Becket had run out of on-hand cash to give to his roommates, and because he was on SIQ, he was not allowed to leave his room. Becket's roommate said he would pay for the items Becket wanted and would pick up more of the requested items, but when he returned to the barracks, the Marine was empty handed and said, "Sorry buddy, I forgot," according to Kiernan.

"My son spent the last two days of his life alone while he was dying in his barracks room without food or even Gatorade or Tylenol," said Kiernan.

On February 4, 2018, three hours before Becket would arrive at Bush Naval Hospital; he called his mother. It was 8:30 a.m. for her in Massachusetts—5:30 a.m. for him in California.

Becket told her about his lack of sleep and the excruciating pain in his right hip and leg as he lay in his barracks room while his roommates blared punk music and Call of Duty.

Becket agreed to go to Bush Naval Hospital on advice from his mother. Kiernan was relieved, believing he would now get the care he needed.

The Marine Corps said Becket's roommates urged him to go to Bush Naval Hospital, and that he was driven there by the Communications Training Battalion Assistant Officer of the Day and his roommate, but per policy at the time, a Marine was not required to stay with him.

Becket's heart rate was racing, and his calves were numb when he arrived at Bush Naval Hospital. A rash had developed on his forehead, and he could hear ringing in his ears.

Naval doctors were discussing options with orthopedic surgeons on how to treat the young Marine. He wasn't responding to fluids or Tylenol anymore, and doctors hadn't a clue as to why he was in such excruciating pain.

"I feel like it's in my muscles," said Becket.

Bush Naval Hospital determined that Becket needed an intensive care unit and contacted Desert Regional Medical Center in Palm Springs, an hour and 10-minute drive south of Twentynine Palms.

There were no Marines from Becket's chain of command at Bush Naval Hospital or when he was transferred to Desert Regional. He was alone.

Captain Joshua Pena, a Marine spokesman, said Becket's company command first went to Bush Naval Hospital on February 5, 2018, around 7 a.m., thinking he was there but learned he had been transferred to Desert Regional.

A spokesman for Bush Naval Hospital told Newsweek in an email that because of HIPAA and patient privacy regulations, they could not discuss any details about the patient, including what time the hospital had informed Becket's leaders that he had been transferred to Desert Regional Medical Center, or if he had been transferred at all.

Colonel Ford, the commanding officer at Becket's school, said the battalion executive officer and the assistant officer of the day was aware that Becket had been transferred to Desert Regional and was receiving updates; however, he did not know why Becket's company leadership had not been informed.

Later that evening, just as the day ticked over to February 5, Kiernan received two phone calls from Desert Regional. She was told about Becket's severe infection and was advised to book a flight immediately. Kiernan headed for Logan International Airport in Boston. It was 5:30 a.m. on February 5, 2018, when her plane took off.

Becket was rushed into the operating room for a fasciotomy, a surgical procedure in which the outer layer of skin is cut to relieve tension in a specific area of tissue. Surgeons discovered Becket had necrotizing fasciitis, a rare, dangerous flesh-eating bacterial infection that destroys tissue beneath the surface of the outer skin.

Kiernan's plane landed at O'Hare International Airport in Chicago for a layover. It's 10 a.m. for her, 8 a.m. for Becket.

Rushing off the plane, she called Desert Regional and pleaded for information. Someone finally told her the diagnosis.

Kiernan recalled the doctor's words: "'Anyone who loves this boy needs to be here right now."

"I was panicked, begging them to tell Becket that I was coming, but I still had to take another four-hour flight."

Over the next two-hours, Becket's condition became unstable as his blood pressure dropped—he died. It was 10:30 a.m.

First Sergeant Becker was in the middle of driving to Desert Regional to check on Becket when he received the news that he had coded shortly after 10:30 a.m. The Marine Corps said he was traveling to the airport.

On the four-hour flight from Chicago to California, Kiernan was unaware of the news to come.

The aircraft touched down at Palm Springs International Airport. Kiernan received a text message from O'Shea: "Ma'am, we're here."

It's 12:30 p.m. and two hours too late.

O'Shea, Becker and a Navy chaplain led Kiernan into a storage room at the airport and broke the news. Not one of the three men was wearing a uniform—a breach of Defense Department regulations and tradition, which treats a casualty notification as a solemn event.

The Marine Corps told Newsweek via email that when command representatives departed Twentynine Palms to meet up with Kiernan at the airport, they were dressed in appropriate civilian attire to escort her in public because the uniform of the day—the woodland camouflage uniform—was not authorized for wear off the base.

However, base policies and Marine Corps orders reviewed by Newsweek indicate Marines were authorized to wear either the bravo or charlie service uniforms off-base.

Once Becket had died, the men obtained a copy of Marine Corps Order 3040.4, the regulations that outline the casualty assistance program, "to ensure adherence to Marine Corps Policy for notification of next of kin," according to the Marines.

Under the order, "Personal notification will be conducted in the Service Alpha uniform. If extenuating circumstances require the wear of the Dress Blue uniform, permission must be requested through the MFPC [casualty section at Headquarters, Marine Corps] prior to the execution of the notification. The uniform for commander-requested very seriously ill or injured (VSI) condolence calls or assistance visits is the Service Charlie or Bravo uniform."

"It shows a lack of respect and a lack of adherence to Marine Corps values," said Kiernan.

Colonel Ford told Newsweek that Becket's leaders did not expect him to die so suddenly and they believed if they had gone and changed into their uniforms, they would have missed Kiernan's arrival at the airport. Ford added that it was now policy to wear a service uniform off base when in doubt.

Kiernan's next memory was at Desert Regional. She's in a big room with Becket's medical team.

Kiernan was in hysterics, rambling on about the days and hours that led up to his death.The detail most prevalent in Kiernan's mind was that Becket had been alone. The command representatives en route to the hospital to be by Becket's bedside were blocked from seeing him once they arrived because he had already died, said Kiernan. The Marine Corps said Becket died while they were there.

Doctors said Kiernan could go in and see Becket. She sat with her son for about two hours, crying too hard to speak.

She remembered his eyelashes being long and his hair being soft like when he was a baby. The hospital had cut the tubes that had attempted to save his life and changed the sheets, tucking him in with clean blankets, "They tried to make him look as nice as possible," Kiernan said.

The fluids that had been pumped into Becket's body made his neck and face appear swollen Kiernan remembered, but at this moment, Becket was a baby again as she stroked his face and hair.

On February 4, 2019, a day before the first anniversary of Becket's death, Kiernan received a text from one of Becket's doctors at Desert Regional. The doctor said the medical team all talk about and remember Becket. They knew within minutes how polite, kind and smart he was and they loved him.

Major O'Shea also texted Kiernan and said the whole schoolhouse was thinking about Becket, his sisters and her. O'Shea said they had dedicated a mass in honor of him and that he would be mentioning Becket at company formation.

Three months after Becket's death, O'Shea instituted a new medical care policy for Company B. The document obtained by Newsweek outlined procedures for Marines on SIQ or needing treatment and transportation to AMCC, Bush Naval Hospital or any facility off base.

In anticipation of Newsweek's publication, all staff noncommissioned officers and officers assigned to the Communications-Electronics School were ordered to undergo Casualty Assistance Calls Officer training.

Life After Death

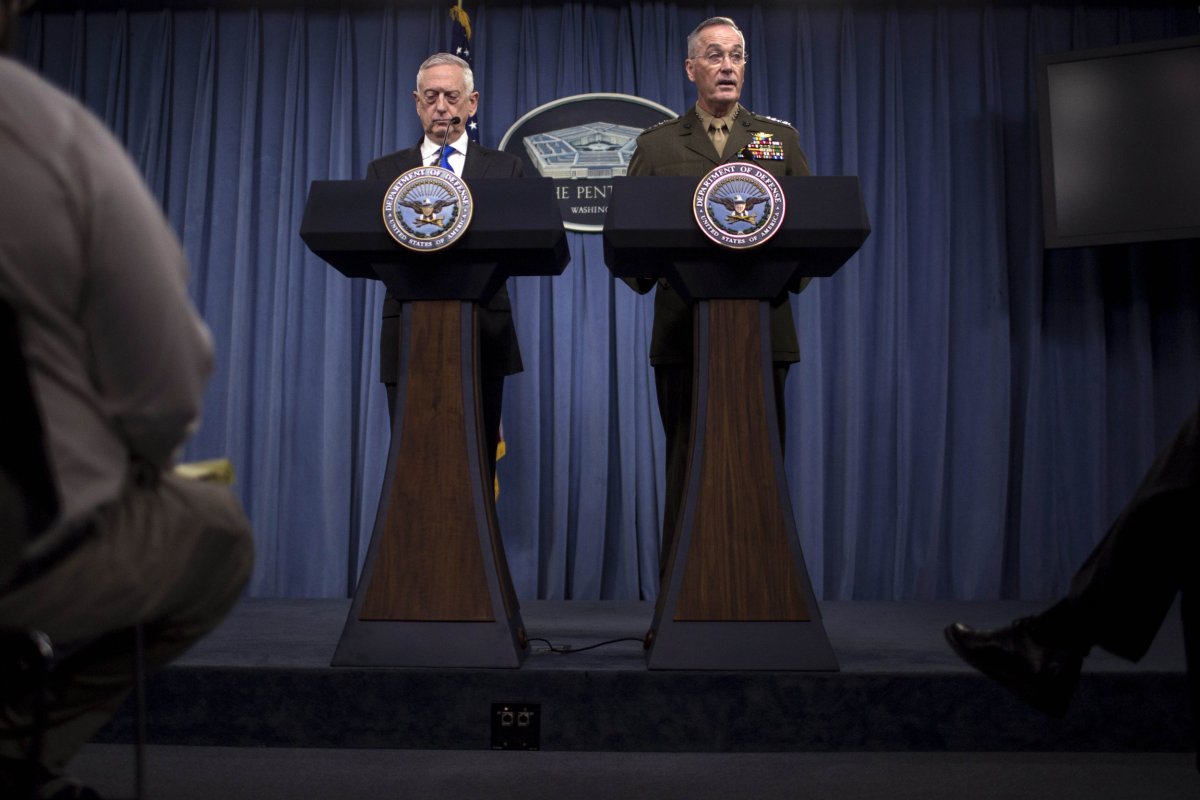

Three months after Becket's death, Kiernan wrote multiple letters to senior Pentagon leaders and her state representatives. She wrote to then-Defense Secretary James Mattis and General Robert Neller, the commandant of the Marines Corps.

She talked about Becket and his lifelong pursuit to become a Marine, and how her "soul is screaming every day from the horror of it all."

Kiernan outlined changes she would like to see made across the Marine Corps and called for an investigation into the "negligent, careless and dismissive medical 'treatment' provided by AMCC and Bush Naval Hospital."

Colonel Ford ordered a command investigation into Becket's death on February 15, 2018, per protocol, and found his death fell into the "line of duty" and that there was no misconduct on the part of the Marines. The investigation did not look into medical malpractice.

Mattis ordered the Marine's inspector general to look into Kiernan's allegations. In July 2018, Carl Shelton Jr., the deputy inspector general of the Marine Corps, wrote to Kiernan and said her inquiry had been forwarded to the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED).

"They are currently gathering information necessary to provide you a substance response to address your inquiry," Shelton wrote.

Lieutenant Colonel Woodward and Kiernan's casualty assistance officer attempted to get her updates on the medical investigation, but they were blocked.

By August 2018, Kiernan would learn that she would not receive answers as to what BUMED's investigation found. Major General David A. Ottignon wrote Kiernan and said a law protects the medical quality assurance records from being released and participants in the investigation are granted immunity.

What Ottignon did say was that BUMED's review was extensive and evaluated all medical care provided to Becket and examined the role of health care providers, facilities and support systems. BUMED identified steps that should be taken to improve its health care services, and that they were evaluating to see if improvements needed to be made across the Navy and Marines Corps.

But Kiernan is determined not to let her son's death be in vain; she wants future Navy corpsman to learn the lessons of his tragic story, and so she was able to get a letter to Vice Admiral C. Forrest Faison III, the surgeon general and chief of Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

Kiernan asked for help at getting answers from the BUMED investigation, but she also talked about wanting Becket's story to be incorporated into the training curriculum at the Navy's hospital corpsman 'A' school at the Medical Education and Training Campus, located at Joint Base San Antonio, Fort Sam Houston in Texas.

In October 2018, Faison indicated that there was an opportunity to honor the memory of Becket by using his tragic death to teach future hospital corpsman.

A day before the Marine Corp's birthday in November, Kiernan was able to get a letter to General Neller. She again asked for help in finding out the results of the BUMED investigation. A month later, Ottignon sent another letter expressing his condolences for the loss of Becket and the barriers of federal law.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

James LaPorta is a senior correspondent for Newsweek covering national security and military affairs. Since joining the magazine, Mr. LaPorta has extensively ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.