It's the next great frontier for human space exploration: Governments, entrepreneurs and space agencies are racing to put boots on Mars.

Two rovers—Europe's ExoMars and NASA's Mars 2020—are slated to lift off for the red planet next summer. These robotic laboratories will search for evidence of life on Mars and help scientists understand the extreme conditions human travelers will have to overcome.

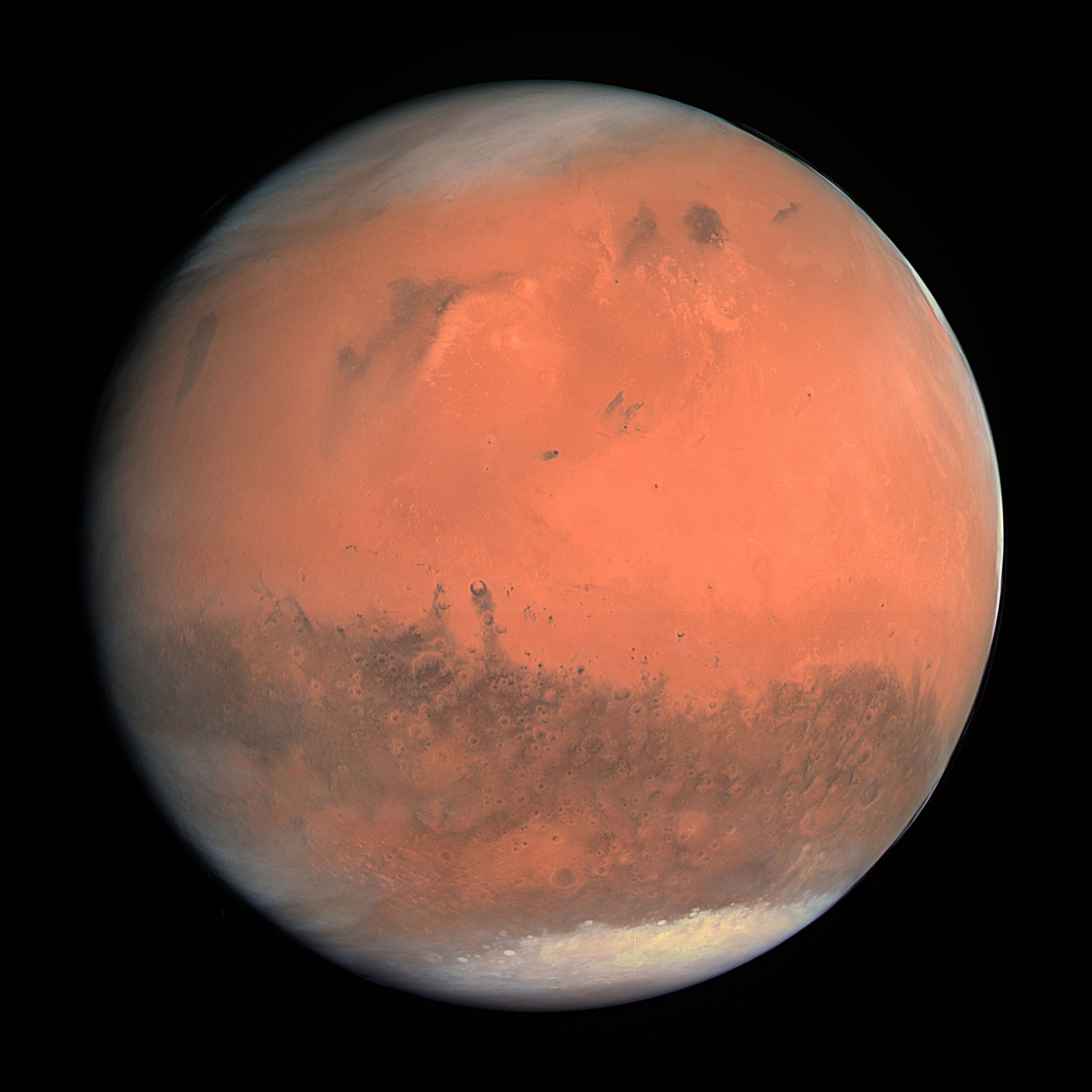

Scientists think that billions of years ago, the orange orb was very much like our own planet. "It once had an atmosphere that was very similar to Earth. It once had a liquid ocean," British astronaut Tim Peake told Newsweek at a recent European Space Agency (ESA) event. "If you're looking for signs of life elsewhere in the solar system—or elsewhere in the universe—then Mars is an exceptionally good place to start looking."

The ExoMars rover—recently named Rosalind Franklin, after the British chemist who helped uncover the structure of DNA—is set to land on the bed of what was once a Martian ocean and is now an arid patch of clay. The robot will probe what lies beneath with a drill that can bore some 6 feet below the surface. In the first exploration of its kind, scientists hope "Rosie" will dig out evidence of ancient life—fossilized molecules that could be lurking deep below.

"The search for life is what ExoMars is all about," David Parker, the ESA's director of human and robotic exploration, told Newsweek. "Is DNA something universal? We don't know…. All of our molecules have a symmetry. If we find organics, are they handed the same way as they are on Earth or the other way? Rosalind may tell us something about if there's a common origin of life in our solar system."

Beyond the question of life itself, ExoMars and other missions will help scientists understand how to live on the red planet. "It's about the physical environment on Mars—the atmosphere, the radiation environment, the dust. We don't know very much about that and the effect it might have on humans," Parker said.

Studying a dried-up ocean could help researchers figure out how to access water on Mars, he added. "Eighty percent of the cost of exploration is transportation. If we can reduce the amount of stuff we take with us in exploration, can we live off the land?"

But even getting a rover to the Red Planet is no mean feat. Peake said the success rate for landing objects like rovers on Mars is only about 50 percent. "The Martian atmosphere is very, very thin. Parachutes don't work very well, aerodynamic breaking doesn't work like it does on Earth. So it's very hard just to get the heavy rover on the surface of Mars," Peake said.

In 2016, an ExoMars mission lander smashed into the red planet. Named Schiaparelli, it crashed seven months after it launched from Earth with the mission's orbiter.

ESA Director General Jan Wörner maintains Schiaparelli was a learning experience, not a simple failure. Everything worked, he said, right up until it didn't—when the computer misread the lander's altitude and shut off its engine. "But the good thing is we got all the data," Wörner said.

In 2017, President Donald Trump asked NASA to launch a human mission to Mars by 2033. But Wörner thinks such goals are premature. Unlike SpaceX CEO Elon Musk, 47, who told Axios in November he thought he'd probably put his own boots on Mars, Wörner, 64, doesn't think we'll make it to the red planet in his lifetime.

"People dreaming about going to Mars in the next decades don't think about the danger. They imply it's just another engine, just a propulsion system, and then we are there," Wörner said. "It takes about two years [to travel to Mars]—two years in a harsh environment with all the radiation. So far, we have no spacecraft where humans within would survive that."

Astronauts traveling through space for such a long time would face a raft of problems space agencies still need to solve, he said. Explorers may develop sudden health problems they can't treat on their craft. Or they may encounter technical problems they can't patch up on board.

"Men and women will put their boots on the surface of Mars and even beyond. For sure," Wörner said. "But let's be serious."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Katherine Hignett is a reporter based in London. She currently covers current affairs, health and science. Prior to joining Newsweek ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.