Scientists may have been searching for Martian life in the wrong place, according to a new article published in Nature Geoscience. Instead of combing the Red Planet's surface, research should dig deep within the crust itself.

Far older and more stable than our own planet's subsurface, scientists from Hong Kong, Hungary and the U.S. think it could teach us about the origin of life on Earth.

Digging deep into the past

At some point in the distant past, non-living matter gave rise to living matter. Scientists around the world are searching for an explanation to this fundamental process. Digging is one of scientists' favorite ways to learn about the past. Whether it's ancient buildings, extinct animals or early human tools, soil holds a record of history.

For something as old as the origin of life, however, our planet's geological record is not nearly well enough preserved, the authors write. Because of this, the search for the origin of life on Earth—or the planet's "abiogenesis"—broadly takes place in laboratories.

"The fundamental question of how abiogenesis occurred on Earth may only be answerable through finding better-preserved 'cradle of life' chemical systems beyond Earth," authors of the new article write. "Such an approach might actually teach us more about the origin of life. Because the chemical signatures from the dawn of life have been entirely obliterated on Earth, finding these clues on Mars, a unique site within the solar system, would provide an invaluable window into our own history."

Development of life

On Earth, photosynthesis—the conversion of light into nutrients—fuels a large portion of developing life. On Mars, however, the frozen desert surface exposed to over a billion years of intense radiation may never have been able to host photosynthetic life.

"Mars is not Earth," the authors explain. "We must recognize that our entire perspective on how life has evolved and how evidence of life is preserved is colored by the fact that we live on a planet where photosynthesis evolved."

Some of Earth's early life has been traced to damp, warm sites underground. It is these locations on Mars, the authors argue, that might be the best place to look for non-photosynthetic life. In 2008, NASA's Spirit Rover found evidence of almost pure opaline silica in the Red Planet's Gustav crater. This is mineral evidence, the authors write, of wet, warm sites below the surface of Mars.

"The subsurface—from meters to kilometers (feet to miles) in depth—is potentially the largest, longest-lived and most stable habitable environment on Mars," they report.

New exploration approaches required

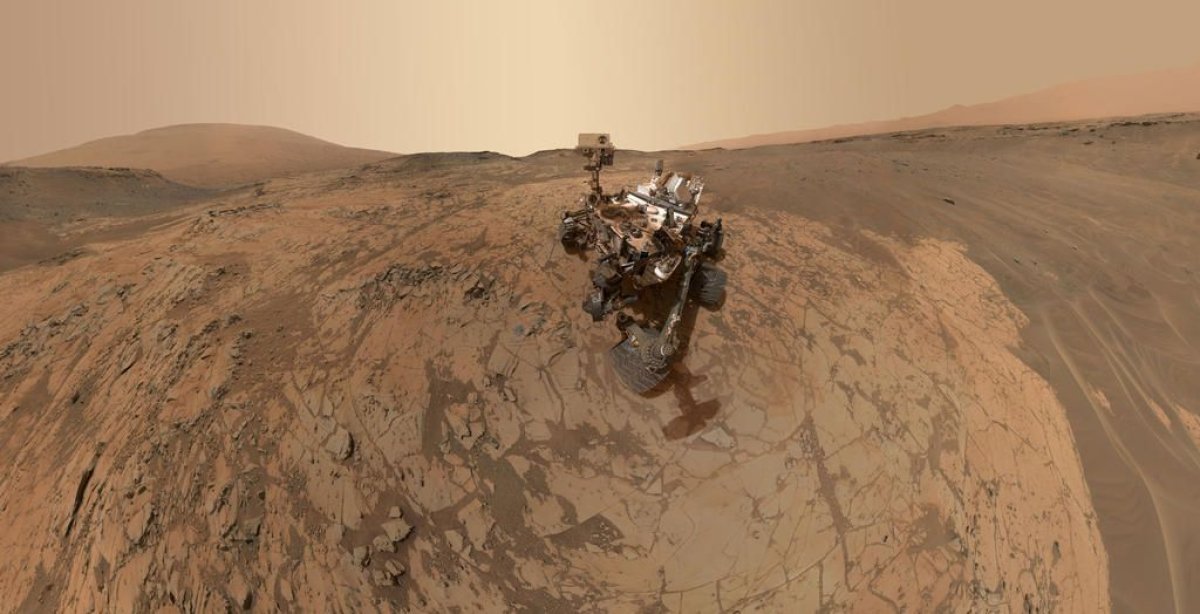

At present, Martian exploration strategies usually target the planet's surface alone for evidence of life. While some drilling has taken place, this has been relatively shallow. The Mars Curiosity rover, for example, has previously drilled into surface rock to collect samples. It cannot, however, drill very deep into the planet's crust.

In fact, its drill is currently out of action following technological problems last year.

This kind of surface-focused approach could be mistaken, the authors write. Given the dim prospect for photosynthesis on Mars, the fingerprints of primitive life on Mars may well linger below the surface. By digging deeper, scientists may be more likely to find preserved markers of life.

"With all of this in mind," the authors write, "It seems time to reconsider the current Mars exploration philosophy."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Katherine Hignett is a reporter based in London. She currently covers current affairs, health and science. Prior to joining Newsweek ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.