Mars once had huge rivers wider than the Mississippi that flowed intensely up until around one billion years ago, scientists discovered. This is long after the Red Planet started to lose its atmosphere, suggesting some "unknown mechanism" of climate-driven precipitation was taking place as it dried out.

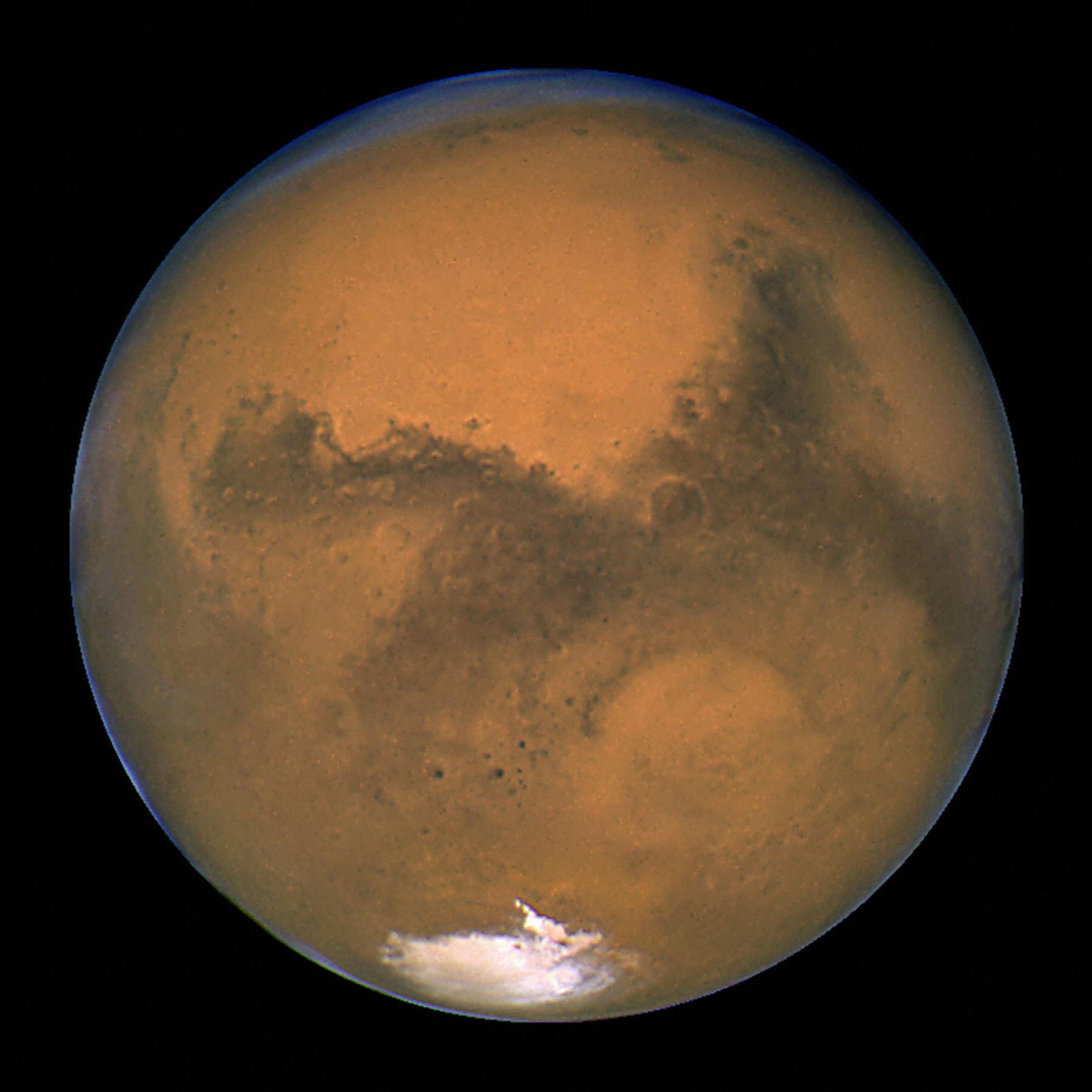

Evidence strongly suggests Mars once had water on its surface. Geological features show that the land had been sculpted by flowing water, while NASA's rovers collected evidence in support of an ancient wet climate—including a Martian rock with clay minerals. Research indicated that around 4 billion years ago, the planet had enough water to cover its surface in a 140 meter-deep liquid layer. This, it is thought, was likely to have pooled into an ocean that would have covered half of Mars's northern hemisphere.

Mars is also thought to have had river systems and major flooding events that would have carved out canyons.

The water, however, largely vanished when Mars lost its atmosphere. Exactly why and when this happened is not known, but as the solar wind—a stream of charged particles from the sun—stripped away the atmosphere, there was no protective layer keeping the water in place. Eventually it evaporated into space.

In a study published in Science Advances, researchers carried out a global survey of Mars to examine the ancient rivers that once existed there. They used imaging data to calculate the intensity of the river runoff, as well as the size of the river channels.

Findings showed Mars's rivers were wider than those found on Earth. "The largest river in our database has a width of around one kilometer [0.6 miles], which is wider than the Mississippi at St. Louis," study author Edwin Kite, from the University of Chicago, told Newsweek. The runoff rate—the amount of water that comes into a river system—was calculated to be 3 kilograms to 20 kilograms per meter squared per day. That amounts to between eight and 50 swimming pools worth of water per square kilometer per day.

The river size and runoff rate was found to have persisted from between 3.6 and 1 billion years ago—and likely lasted beyond this point.

"We expected that late-stage rivers would be narrower (for a given drainage area) than early-stage rivers, but we did not find any evidence for this. Therefore, intense, climate-driven runoff persisted surprisingly late in Mars' history," Kite said.

This finding has a number of implications. It could mean that currently accepted dates for late-stage rivers are wrong, that late-stage atmospheric removal processes were faster than currently thought, or that some other mechanism allowed for precipitation in low-atmosphere conditions. Which of these three scenarios is more likely is unclear—and will remain so without further research, Kite said.

Geronimo Villanueva, a scientist with NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center who studies Mars but was not involved in the latest research, told Newsweek the paper provides new constraints in relation to the Red Planet's water cycle—showing it lasted for a considerable period.

"The challenge is how to explain this early wet scenario in Martian history," he said. "Because Mars is further from the sun than Earth, it should be typically colder and its atmosphere should not be able to maintain liquid water easily. The fact that this paper and others confirm an early active hydrological cycle on Mars demonstrate how little we know about the evolution of the Martian climate, and even more importantly, the evolution of its habitability."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Hannah Osborne is Nesweek's Science Editor, based in London, UK. Hannah joined Newsweek in 2017 from IBTimes UK. She is ... Read more