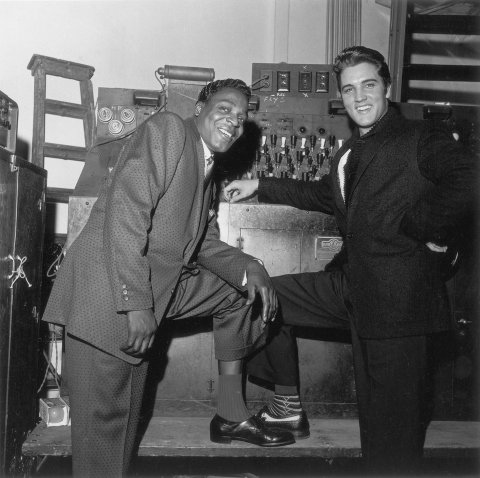

Ernest Withers was a professional photographer when few African-Americans were. A talented hustler who could navigate a brutally segregated South, he had a canny eye for history in the making at a time when history was broiling, during the 1950s and '60s. His work covering the civil rights movement appeared in newspapers across the country.

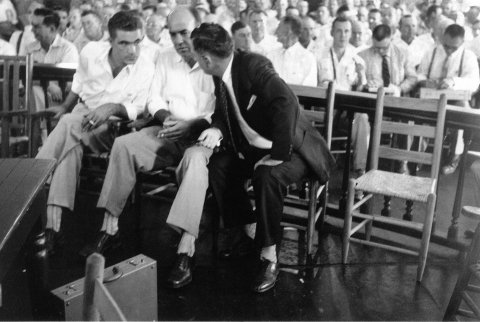

A native of Memphis, Tennessee, Withers was there when Elvis Presley broke through, capturing him visiting the black singers in the Beale Street clubs that inspired his music (and his hips). He also produced powerful images of the Emmett Till murder trial in 1955; the desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957; and the rise of the Black Power movement. One of his most famous photos captures Martin Luther King Jr. riding a newly integrated bus in Montgomery, Alabama, after that boycott ended in 1956.

Withers supported social justice, but his legacy is tangled by a secret association with the FBI. Like many of his generation, he was a patriot; he'd served in the Army during World War II and was disturbed by the anti-war movement of the 1960s. He was a man of his time, too, in his distrust of Communists, whom FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover believed were behind King's civil rights movement and militant Black Power leaders like Eldridge Cleaver. Such feelings, Preston Lauterbach suggests in his new book, Bluff City: The Secret Life of Photographer Ernest Withers (W.W. Norton & Co., January 15), were behind the decision of an African-American photographer to become a well-compensated informant against black activists.

Hoover's Memphis agents were tasked with monitoring local civil rights leaders, including the Reverend James Lawson, co-founder of the Committee on the Move to Equality (COME), which was committed to civil disobedience, and John B. Smith of the Invaders, a Black Power offshoot openly defiant of King's philosophy of nonviolence. Because of his coverage of the movement, Withers was trusted and invited to local meetings. In turn, his photo studio on Beale Street was an unofficial Invaders hangout. He fed his findings to his FBI contact, William Lawrence.

That double life came to a head during the Memphis sanitation workers strike, which began after the accidental death of two workers in February 1968. Hundreds went on strike, and a march was planned for March 22, then rescheduled, because of a freak snowstorm, for March 28. Reverend Lawson was chairman of the strike committee and invited King to speak at the march.

As Lauterbach writes, Memphis authorities were unprepared for a mass march; the largest up to that point had topped out in the low hundreds. This one would measure up to the 1965 Selma-Montgomery campaign in Alabama.

On the night of March 27, King was in New York City, at the home of singer and activist Harry Belafonte. King, the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), established in 1957 to end segregation, had been tirelessly promoting his Poor People's Campaign—with its shift from social to economic injustice—and a planned march on Washington. (The campaign's first phase was the erection of a shantytown, to become known as Resurrection City, on the National Mall, an idea that alarmed Hoover.) King was exhausted, but he and Belafonte spoke late into the night. At dawn he boarded a flight for Memphis.

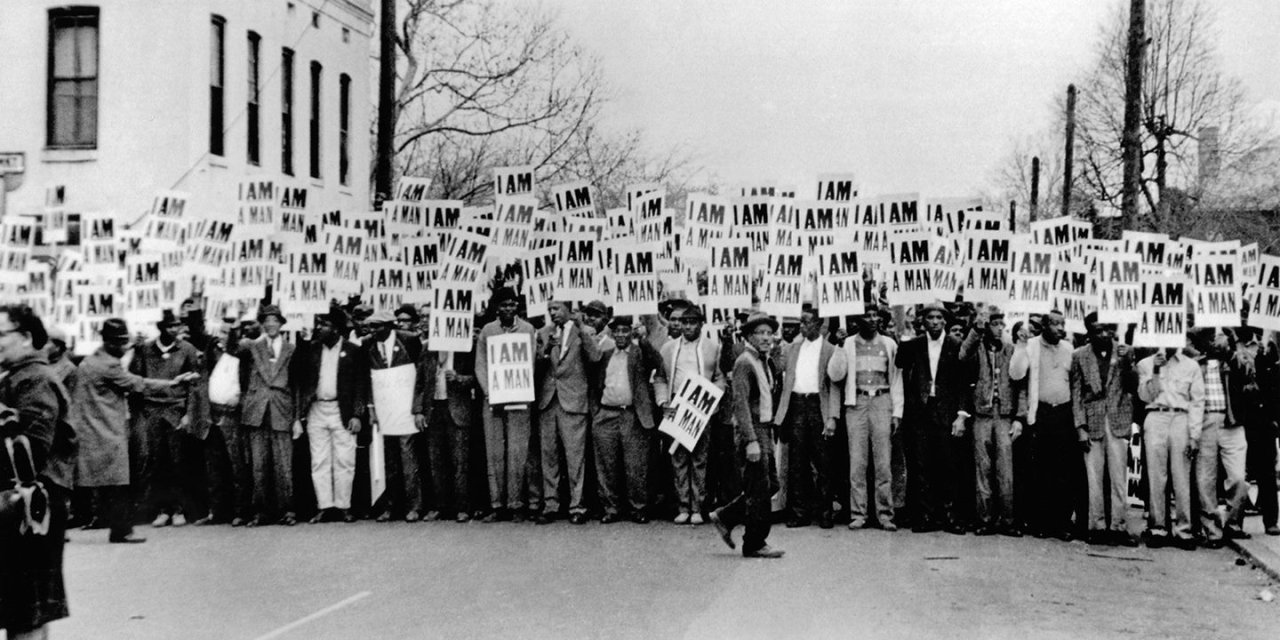

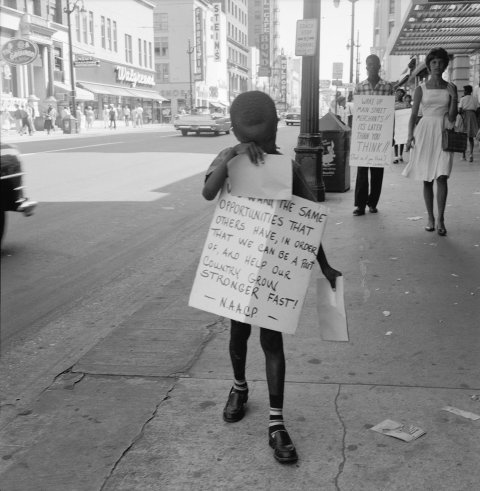

King arrived a half hour late, at 10:30 a.m. When he stepped out of his car, the large crowd became hysterical with excitement. As the march began, writes Lauterbach, "King could have lifted both feet and been propelled by the great momentum behind him." Many of the thousands of protesters were carrying "I Am a Man" signs. Withers had suggested the signs and distributed the lumber to make them, and they would feature prominently in the photographs he'd take that day—and in the events to follow.

His Rolleiflex also captured the clearly shaken King at the head of the crowd, his arm linked with the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, his top man for over a decade. It had been 12 years since Withers had taken the image of King on a Montgomery bus, Abernathy at his side. "King had been 27 on that day in 1956," writes Lauterbach. "Now he was crowding 40. He looked 50."

High school followers of Invaders leader Smith, some armed with tire irons and Molotov cocktails, began to use the "I Am a Man" signs as weapons. Soon conflicts broke out between those protesters and over 300 officers from the city's police department. The demonstration quickly turned into a riot. "King had stood in the eye of extreme violence before, withstanding a police attack in Selma, a racist mob attack in [Chicago suburb] Cicero and a bomb explosion at his home in Montgomery," says Lauterbach. "But never before had one of his marches turned violent from within."

After less than half an hour, King was spirited away in a car. Lawson said later that he had urged King to leave but that he had refused until he was practically forced into the car. Local authorities, however, would say that King abandoned the march, fearing for his safety, without trying to stop any of the violence or property destruction. "The Assistant Chief of Police," writes Lauterbach, "would quote King as saying, 'I've got to get out of here.' The quote would form an important part of an FBI smear campaign to come."

In the end, the police beat and gassed protesters, arresting 300 and shooting four alleged looters. Along the city's famed Beale Street, "glass shards from broken store windows and fractured two-by-twos used for the signs choked the gutters."

The following is an excerpt from Bluff City: The Secret Life of Photographer Ernest Withers, by Preston Lauterbach. (Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.) It begins after King has left the march.

Martin Luther King Jr. lay despondent. After leaving the scene of the riot, he and his group had checked into the Holiday Inn Rivermont, a high-rise hotel overlooking the Mississippi, about a mile and a half from where the march began. They took a suite on the eighth floor. King had got into bed fully clothed and pulled up the covers.

While burning through a chain of Salem cigarettes, he spoke to Abernathy. "Maybe we just have to admit that the day of violence is here," King said. "Maybe we just have to give up and let violence take its course." Abernathy had never seen King like this, nor heard him talk this way. In his depression, King contemplated calling off the Poor People's Campaign.

To lift King's mood, another aide arranged for an important friend to get in touch. Stanley Levison phoned King's room from his home in New York City. An adviser and fundraiser for King's SCLC, Levison had been a faithful friend for many years. As a former affiliate of the Communist Party USA, Levinson had been Hoover's justification for investigating King, as a possible "Red" influence on the civil rights movement.

The bureau tapped Levison's phone and picked up his conversation with King in Memphis. Agents heard King tell Levison that a local Black Power group called the Invaders had incited the riot.

In the confusion of March 28, 1968, it's easy to lose sight of the day's key issue: the possibility that the FBI sabotaged the march. The riot happened during a month of increasing federal anxiety over the Poor People's Campaign and two days after the FBI proposed smearing King to curtail support among potential supporters. If the bureau had indeed encouraged the riot, it would need someone else to blame. Creating a wedge between King and Black Power fit the bureau's objective of preventing the rise of a black messiah who could electrify and unify the black nationalist movement, beginning a true black revolution. The conduct of Lawrence, Withers's longtime FBI handler, in documenting the riot provides clues of treachery.

While King smoked in bed, Withers conferred with Lawrence. The next day, Lawrence finished a long memo about the riot, which the Memphis office sent to Hoover. Lawrence had three sources of information about the demonstration: Withers, Memphis Press Scimitar reporter Kay Pittman Black and a third party whose observations closely match those of Memphis police undercover officer Marrell McCollough, who had infiltrated the Invaders. Addressing the factors that contributed to the violence, Lawrence wrote that Reverend Lawson's COME strike support group had "unwittingly" armed anyone who showed up to march.

The COME group handed out hundreds of prepared placards made of cardboard and carried on long 4-foot pine poles. Before the march, it was apparent to these three sources that many of the young people were planning to use the placards as sticks and clubs because they were indiscriminately ripping the cardboard away, leaving a 4-foot pole in their hands, which many of them waved in a threatening manner.

Lawrence was referring here to the "I Am a Man" strike support posters. Addressing how the two-by-twos became weapons, Lawrence's "source one" for this memo—Withers—made the most specific accusation against an Invaders leader in provoking the riot. "Source one pointed out that prior to the start of the March 28, 1968 march that John [B.] Smith and some of his associates were in his opinion inciting to violence in that they were indiscriminately giving out the 4-foot pine poles to various teenage youngsters in the area and John Smith was heard by source one to tell these youngsters, identities not known, not to be afraid to use these sticks. He did not elaborate as to what he meant."

Later in the summary, Lawrence wrote, Withers "pointed out that as mentioned…these individuals [the Invaders] had done much by their previous statements and actions…to incite some of the more ignorant and greedy youths who were in the march." By "previous statements and actions," Withers reportedly meant the Molotov cocktails that the Invaders had distributed three weeks before the march.

Lawrence's—and the FBI's—explanation for the origins of the riot was that COME had handed out the sticks, the Invaders had instructed the youths in using them as weapons and a nonviolent march had become a riot. But there are problems with this formulation. For one, Invaders leader Smith denied that he had handed out signposts to youngsters at the march or encouraged their use as weapons. Such a denial is what one would expect, but Smith got some pretty strong backup from McCollough, the police officer who'd infiltrated the Invaders. In 1978, McCullough testified to the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA), which was conducting an inquiry into the King assassination. McCollough corroborated Smith's claim.

Another point in favor of Smith came out of the HSCA inquiry itself. The committee conducted a thorough investigation of the riot, using its power to subpoena FBI files and gain access to confidential sources. It studied Lawrence's March 29 memo to headquarters and his source's accusation that Smith had handed out the two-by-twos and told people to not be afraid to use them. The HSCA took testimony from that confidential source and found discrepancies between the informant's testimony and the statements in Lawrence's memo, concluding, "The informant denied having provided certain information that had been attributed to him and placed in his informant file."

When Lawrence himself testified before the committee, he said his sources of information on the riot and the Invaders had been accurate. Afterward, Lawrence told Withers that the HSCA "had asked me if info attributed to [Withers]—in my letterhead memo [of March 29] had actually been furnished by him—and I had to reply that it had been." Lawrence acknowledged that he couldn't tell Withers what to say to the HSCA but warned him that "denying that he had ever furnished info which I attributed to him…would nevertheless create a situation indicating that He or I had perjured ourselves in that I said one thing and he another."

The HSCA leveled no perjury charges but concluded that "the discrepancy tarnished the evidence given by both the Bureau and the informant, and it left the committee with a measure of uncertainty about the scope of FBI involvement with the Invaders."

As Lawrence said, someone perjured himself about the Invaders in the riot. All the evidence indicates that it was Lawrence who fabricated the story of Smith inciting violence and misattributed this version of events to his "source one" informant, Withers.

In the months following the 1968 riot, Lawrence would repeat the Smith story with greater embellishment. In a lengthy report dated May 6, 1968, he upgraded the statement about the sticks to a direct quote: "[Withers]…recalled hearing John B. Smith tell some of the youngsters, 'Don't be afraid to use these sticks if you have to.'" Perhaps the strangest thing is that Lawrence never pursued the matter further, indicating that his case against Smith must have been weak.

The FBI never arrested or prosecuted Smith on charges associated with the riot, despite the evidence in its files that he had incited it. The evidence shows that the FBI falsely used Withers as a source of untrue information—a revelation, if not one that clarifies the bureau's role, or Withers's, in spoiling King's final march.

While Lawrence inaccurately held Smith responsible for inciting violence in his March 29 memo, he failed to disclose his informant's own proximity to the signs used that day as weapons. In a May 6, 1968, report, Lawrence wrote, "[Withers] pointed out that the COME group had organized the march and had made a bad mistake by giving out several hundred pre-constructed pasteboard placards which had been stapled onto long pine poles or sticks." The distribution of the poles appears here as a "bad mistake" on COME's part, according to Withers, the person who had actually brought the lumber to the strike.

Lawrence rehashed the story of the two-by-twos even more vividly later in the report. He wrote: "On the night of March 28, 1968, [Withers] advised that the biggest definite contributing factor to the violence in his opinion was the fact that the COME group had for the first time in any of their numerous daily marches furnished wooden sticks to the marchers, as previously they had merely used cardboard placards which could not become lethal weapons. He pointed out that giving out several hundred hard pine sticks was tantamount to giving out an equal number of baseball bats which could easily be used to break windows and which could be used as weapons by the participants in the march."

Again, it seems strange that the person who supervised bringing the sticks to the march—Withers—could so quickly claim that what he had done "was tantamount to giving out an equal number of baseball bats." In neither instance did Lawrence note Withers's role in putting the two-by-twos into play, though he seems to have been aware of it. In a memo to the Memphis office dated April 2, 1968, Lawrence provided deeper detail on the origin of the sticks. "[First name unknown] Harvey, brother of Fred Harvey, and who is a teacher at Jeter High School, earlier in the week…rent[ed] a Skil saw which was taken to the Minimum Salary Office of AME Church next to Clayborn Temple, where J.C. Brown cut the pine wood into four-foot lengths for the placards."

Much of this memo has been redacted. But those names—Harvey and Brown—corroborate what Withers told a German sociologist in 1982: "If anybody is…responsible for that riot up there, as anybody, I might be responsible…because I and Harvey and J.C. Brown back here went down…there to rent the saw to cut the sticks that was used in the riot, and we certainly wasn't doing it by plan."

Also on April 2, Hoover may have directed the use of FBI funds for some yet unknown endeavor. A teletype from him to the Memphis bureau that day reads in part (the document is heavily redacted): "In the event it is necessary to [name redacted] for actual expenses incurred, authority is granted to pay him up to seven five dollars. If payment is made, -obtain itemized accounting of his expenses." Lawrence's -signature appears, acknowledging receipt of Hoover's memo. Perhaps the FBI Memphis memo describing the construction of the signs and the teletype with Hoover's payment authorization also contain information linking the FBI to the two-by-twos. But until we are able to view unredacted copies of both, we'll never know. ■

Lauterbach notes that it remains unclear whether the signs Witherssuggestedwere to create a stronger visual or if, as the FBI suggested, there was a hope of encouraging violence among the strikers.

Whatever the intention, the photographer's action tragically altered the course of the civil rights movement. King felt the violence was a stain on his leadership. A week later, on April 3, he would return to Memphis to restate his plea for nonviolence, delivering his triumphant "Mountaintop" speech ("I have seen the promised land.…"), which poignantly hinted at his mortality. The following evening, on April 4, King was shot on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel by James Earl Ray. "If the windows on Beale Street hadn't been broken," Lauterbach writes, "King would have had no reason to come back."

Memphis ministers, black and white, pleaded with Memphis mayor Henry Loeb to concede to the sanitation workers' union's demands. He would not. It took President Lyndon Johnson to force his hand. A solution to the strike was negotiated on April 16, ending the strike. Workers received a pay raise of 15 cents an hour.

King's Poor People's Campaign went forward. Resurrection City, the first stage, was erected on the National Mall (population 3,000), culminating in the Solidarity Day Rally for Jobs, Peace and Freedom on June 19, 1968.

It wasn't until 2010, three years after Withers's death, that his work for the FBI was revealed in a series of articles by Marc Perrusquia in The Commercial Appeal, a Memphis newspaper that sued the FBI to open the Withers informant file,which Lauterbach used to research Bluff City. Despite incriminating evidence, he writes that even during Withers's years as an informant, his "courage and commitment through the most physically threatening and emotionally trying times of his life are beyond reproach."

Withers's association with the FBI ended in the late '70s. The decades of compensation allowed the photographer to put his eight children through college. By the '80s, his work was famous, exhibited all over the country. He spent the last two decades of his life, until his death in 2007, publishing books and delivering lectures.

The Withers Collection Museum and Gallery remains on Beale Street, evidence of a rightfully celebrated if imperfect artist—a man who "personifies the flawed hero," writes Lauterbach. "I think we need to embrace him for all he was."

Bluff City: The Secret Life of Photographer Ernest Withers, by Preston Lauterbach (W.W. Norton), will be released January 15. You can find it here.