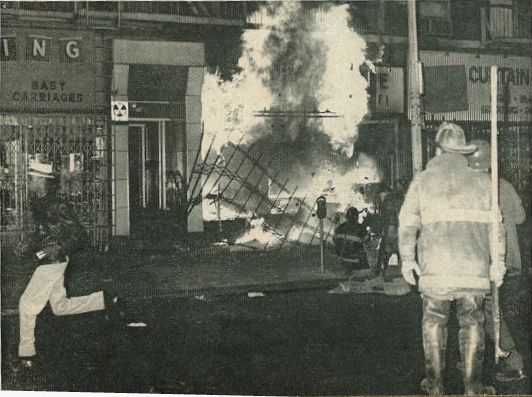

Photos: The Rampage That Came After Martin Luther King Jr. Was Slayed

In the week following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, a fury of riots broke out in dozens of cities across the United States. The rampage left 39 dead, 21,000 arrested, more than 2,600 injured and was responsible for damages estimated at $65 million. Not since the Civil War had the country been subject to such a violent and widespread wave of social unrest. The above photos and following story, which originally appeared in the April 15, 1968 issue of Newsweek, provide a behind-the-scenes look at the looting and burning of the cities and the toll it ultimately took on the nation.

"Take Everything You Need, Baby"

Newsweek, April 15, 1968

It was Pandora's box flung open—an apocalyptic act that loosed the furies brooding in the shadows of America's sullen ghettos. From Washington to Oakland, Tallahassee to Denver, the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis last week touched off a black rampage that subjected the U.S. to the most widespread spasm of racial disorder in its violent history.

The fire this time made Washington look like the besieged capital of a banana republic with helmeted combat troops, bayoneted rifles at the ready, guarding the White House and a light-machine gun post defending the steps of the Capitol. Huge sections of Chicago's West Side ghetto were put to the torch. The National Guard was called out there and in Detroit, Pittsburgh, Baltimore and in four Southern cities, and put on alert in Philadelphia and Boston. In New York, Mayor John V. Lindsay was heckled from a Harlem street by an angry crowd. In Minneapolis, a Negro vowed to kill the first honky he saw—and promptly shot his white neighbor to death. "My King is dead," he sobbed, after pumping half a dozen bullets into his victim.

Negro college campuses seethed with anger and sometimes harbored snipers. Dozens of high schools canceled classes after violence erupted between Negro and white students. Window-breaking, rock-throwing, looting and other acts of vandalism struck a score of cities, large and small. Washington, Chicago, Detroit and Toledo tried to enforce dusk-to-dawn curfews. Bars, liquor stores and gun shops were closed in many places, but usually not before ghetto blacks had stocked up on alcohol and ammunition. Throughout the country, already-overburdened police and firemen went on emergency shifts. By the weekend, the death toll around the U.S. stood at more than twenty and was rising, uncounted thousands were under arrest (more than 4,000 in Washington alone) and property damage was incalculable.

King's assassination was quite clearly the proximate cause of it all—but the rioters' anger and grief was often hard to detect. The Chicago mobs were ugly and obviously well schooled in the use of fire bombs. But in Washington the looters had a Mardi Gras air about them. Around the country, whites were jeered, threatened and occasionally assaulted, but the crowds generally avoided confrontations with the police. The police, too, did their best to keep bloodshed at a minimum. Indeed, in city after city, the cops were under orders not to interfere with looting. And it was quite apparent that the rioters' main target was to loot, not shoot honkies. "Soul Brother" signs afforded Negro businessmen little of the protection they assured in past riots. The plunderers—led by black teen-agers—smashed and burned almost indiscriminately.

'Guns': Washington, which is 66 percent Negro but which had been almost untouched by the last four riotous summers, was the hardest hit this time. Minutes after the news of King's death was broadcast, crowds began to gather on the edges of the Capital's sprawling ghettos. They did not have to wait long for a leader. Into the volatile mix swept black power-monger Stokely Carmichael spouting incendiary rhetoric. "Go home and get your guns," cried Carmichael. "When the white man comes he is coming to kill you. I don't want any black blood in the street. Go home and get you a gun and then come back because I got me a gun"—and he brandished what looked like a small pistol.

Roving bands of black teen-agers—unarmed so far as anyone could tell—were already darting into Washington's downtown shopping district, fires were beginning to light the night sky and Washington's relatively small (2,900-man) police force went on the alert. The plundering and burning lasted until dawn, then subsided—only to resume with far greater intensity the next day.

Friday was a crisp spring day in the Capital. The cherry blossoms were in bloom and the city was thronged with tourists who gawked in amazement through the tinted windows of their sightseeing buses as the rampage resumed.

The Frisk: At his storefront headquarters, Stokely Carmichael helped feed the flames with more violent talk—all of it delivered in a soft, gentle voice to newsmen (who were frisked and relieved of such potential weapons as nail clippers before being admitted to his presence). "When white America killed Dr. King," said Carmichael, who bitterly opposed King's nonviolent stance, " she declared war on us ... We have to retaliate for the deaths of our leaders. The executions of those deaths [are] going to be in the streets ..." Did Carmichael, 27, fear for his own life? "The hell with my life," he snapped at a white reporter. "You should fear for yours. I know I'm going to die." Later, he turned up at a memorial service for King at Howard University, waving a gun on the platform.

As the day wore on, the turmoil increased. Looting and burning swept down 14th Street and 7th Street, two of the ghetto's main thoroughfares, then spread south to the shopping district just east of the White House. On the sidewalk in front of the Justice Department's headquarters on Pennsylvania Avenue, shirt-sleeved DOJ staffers watched helplessly as looters cleaned out Kaufman's clothing store. The story was the same all over. Without the force to control the situation, the cops let the looters run wild. The result was an eerie, carnival atmosphere. Jolly blacks dashed in and out of shattered shop windows carrying their booty away in plain sight of the Jaw. Others tooled through the shopping districts in late-model cars, pausing to 611 them with loot and then speeding off only to stop obediently for red lights.

Looters stopped on the sidewalks to try on new sports jackets and to doff their old shoes for stolen new ones. Only rarely did police interfere. At the corner of 14th and G Streets, police braced a Negro over a car. On the hood were several pairs of shoes. "They killed my brother, they killed Luther King," the culprit cried. "Was he stealing shoes when they killed him?" retorted a cop.

Marketing: White reporters moved among the plunderers with impunity. "Take a good look, baby," a looter cried to a carload of newsmen as he emerged from a liquor store on H Street. "In fact, have a bottle"—and he tossed a fifth of high-priced Scotch into the car. Young black girls and mothers, even 7- and 8-year-old children, roamed the streets with shopping carts, stocking up on groceries. "Cohen's is open," chirped one woman to friends as she headed for a sacked dry-goods store with the nonchalance of a matron going marketing. "Take everything you need, baby," Negroes called to each other from shattered store windows. Mingling with the crowds on Pennsylvania Avenue were observers from the German, French, Japanese, Norwegian and other embassies, taking notes to cable home. "It's a revolution," a French Embassy attache remarked to his companion.

It wasn't. But the sacking of Washington was ugly enough. By midafternoon—with an acrid pall of smoke hanging over the White House and looting going on less than two blocks away—frightened whites and Negro office workers tried desperately to get home, creating a massive traffic jam. Telephone lines were clogged, water pressure was running low and at least 70 fires were blazing. White House aide Joseph Califano set up a special command post to monitor the situation right on the Presidential doorstep. Finally, Lyndon Johnson declared that the Capital was caught up in "conditions of...violence and disorder" and as Commander in Chief he first called in some 6,500 Army and National Guard troops, including a contingent stationed on the grounds of the White House itself.

Stability: When looters and pillagers continued to roam the streets, the President ordered in 6,000 more Federal troops. And by late Saturday night, the combined forces finally restored some semblance of stability to the Capital.

If the Washington disorders had a bizarre gaiety to them, the scene in Chicago—where King had led an abortive "End Slums" campaign in 1966—was bittersweet. Deadly sniper fire crackled in the South Side slums, and the West Side—the scene of two major riots since 1965—blazed with more fires than anyone could count. There was no mistaking the anger of the young blacks, who watched with solemn satisfaction as whole blocks went up in flames. "This is the only answer," said one studious-looking Negro youth as he peered at the flames through gold-framed spectacles. "It feels good," said another, munching a vanilla ice-cream cone. "I never felt so good before. When they bury King, we gonna bury Chicago."

With the tongues of flame dancing against the sky, the talk of the streets sounded like an invitation to Armageddon. "I thought I was dead until they killed the King," intoned a 24-year-old gang leader in a black leather coat. "They killed the King and I came to life. We gonna die fighting. We all gonna die fighting."

There was little fighting in Chicago. But at least nine Negroes were killed there, mostly in the act of looting. As elsewhere, the police who pegged shots at looters were the exceptions to the rule. And so the plundering went on almost unopposed. Along Kedzie Avenue on the West Side, Negroes carried armfuls and cartloads of booty from ravaged storefronts. "I'm a hard man and I want some revenge," explained one. "King's dead and he ain't ever gonna get what he wanted. But we're alive, man, and we're getting what we want."

'Bums': Nearby, a Negro woman begged the vandals to stop. "Come out of that store and leave that stuff," she shouted. "You all nothing but bums. Ain't we got enough trouble with our neighborhood burning down? Where are those people gonna live after you burn them down?" Unhearing—or uncaring—the looters ignored her.

Chicago Mayor Richard Daley had pleaded for peace on TV after King's murder, but his words, too, fell on deaf ears. Finally, with vast areas of the slums in chaos, the National Guard was ordered in. Three thousand guardsmen, many of them black-rolled into the ghetto, with 3,000 more held in reserve. The troops patrolled mostly in four-man Jeeps: a driver armed with a pistol, one man with a carbine and two armed with M-1 rifles. Unlike the green and triggerhappy guard units who performed so ineptly in Detroit and Newark last summer, the lllinois troops were poised enough to handle matters with a minimum of bloodshed. But when the situation heated up again the next day, state officials requested that 5,000 Federal soldiers be deployed to back up the guard. In the end, 12,500 troops were required to bring Chicago back under shaky control.

With disorder sweeping the country, New York, which suffered the nation's first major riot in 1964, braced for trouble. It came soon enough. The immediate post-assassination hours brought a spate of window-breaking and looting to Harlem and in the teeming Bedford-Stuyvesant slum in Brooklyn. Mayor John Lindsay, whose walking tours of the ghettos helped keep the city cool last summer, sped to Harlem to commiserate with the crowds over King's death and defuse the situation. He walked along 125th Street, patting passers-by on the back, then took a bullhorn to speak to the crowds. In a quivering, emotional voice, he began by addressing the Negroes as "Brothers"—a term soul-minded blacks like to use. The mayor barely got in another word. "You got some nerve using that word," one angry youth shouted at Lindsay. Others hurled obscenities at the mayor.

Plea: The next night, Negro youths rode subways to midtown, breaking windows in shops near Central Park and dogtrotting through Times Square. But the police were ready for them, deftly breaking up the roving bands and maintaining order without firing a shot. At the weekend, the mayor was back on the city's slum streets for the third night in a row and, in the end, he prevailed as an effective force in keeping the racial lid from blowing off in New York. Amidst rising tensions, Lindsay had gone on television to plead for continued calm—"lt especially depends on the determination of the young men of this city to respect our laws and the teachings of the martyr, Martin Luther King"—and to promise better days ahead. "We can work together again for progress and peace in this city and this nation," he said, "for now I believe we are ready to scale the mountain from which Dr. King saw the promised land."

Perhaps he was right. But the convulsions unleashed by a sniper in Memphis left the nation with ominous questions still to be answered. Were last week's riots a final paroxysm that might purge angry emotions and clear the way for reconciliation? Or were the pictures of the machine gun on the Capitol steps and Chicago in flames only premonitions of an America without Martin Luther King?