Seif al-Din Mustafa's five-hour takeover of an EgyptAir jet on March 29 could have ended in tragedy. Instead, it ended in farce. The suicide vest with which the 59-year-old Egyptian hijacker had threatened to blow up the plane turned out to be a crude fake. British passenger Ben Innes, a health and safety auditor from Leeds, England, even posed grinning alongside the bomber for the week's most infamous selfie (although, as the Internet quickly reminded us, the portrait of the two men wasn't technically a selfie).

But for co-pilot Hamad el-Kaddah, the hijacking was no laughing matter. Just minutes after takeoff from Alexandria for a 45-minute flight to Cairo, two members of the cabin crew knocked on the door of the flight deck. They had a terrifying message from one of the passengers: "Captain, the plane is hijacked. Go now to Cyprus, Turkey or Athens," recalls el-Kaddah, 32, speaking exclusively to Newsweek in Cairo. "If you land in any of the Egyptian land airports, it will be only one press on the button, everything will go, everyone will die. It's your decision."

Captain Amr al-Gammal diverted the plane to Larnaca International Airport in Cyprus, where the hijacker allowed women and children off the plane. Then he released all the Egyptians, finally keeping just five foreigners and some of the crew as hostages. "The point is not if you are going to die or not," says Kaddah, who volunteered to remain as the last hostage before making a dramatic escape through the cockpit window. "The point is that you have a lot of people that are going to die with you, so this is what you care about. The passengers were the main concern for us."

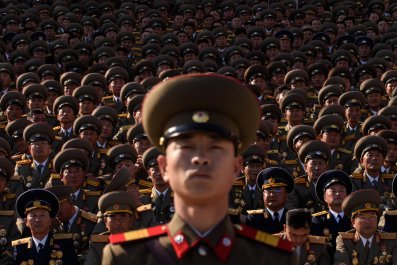

Mustafa's motives were personal. A convicted fraudster, he demanded to see his Cypriot ex-wife upon landing on the island. But for all the semi-comical elements to the hijacking, the incident came at a time of heightened threats from Islamist extremists, three of whom attacked Brussels's Zaventem airport on March 22, and it raised further concerns about airline security. And after a Russian Metrojet aircraft was blown up last October over Egypt's Sinai Peninsula following takeoff from Sharm el-Sheikh International Airport, killing all 224 people on board, Egypt is once again the focal point of the debate.

On the defensive, Egypt's Ministry of the Interior quickly shared pictures of the scans of Mustafa's bag and footage of him going through airport security. Nothing in his luggage triggered suspicion.

"We should keep what happened in Alexandria separate from the Metrojet incident," says Sajjan Gohel, international security director at the Asia-Pacific Foundation, a London-based think tank. "The Metrojet [bombing] showed a clear security failure. There was collusion between the Sinai branch of the Islamic State with ideologically sympathetic members of the security services that allowed them to smuggle a bomb on board. But [Mustafa] put together his mock explosive device after going through security, not before. In fairness to the Egyptians, this could be replicated anywhere."

The issue, aviation security experts say, is whether today's airport security procedures are adequate and whether security officials ought to spend more time analyzing individuals' behavior. Most current airport security measures focus on physical screening of luggage—a measure that has significantly reduced the number of hijackings involving metal weaponry such as guns and grenades, once commonplace in hijackings in the 1970s and '80s.

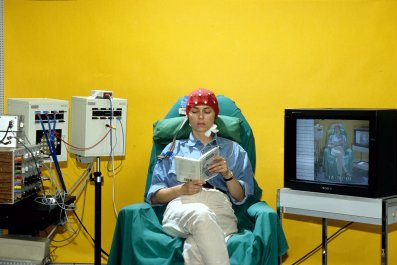

"Our current security architecture identifies substances and weapons, not negative intent," says Philip Baum, author of the newly published book Violence in the Skies: a History of Aircraft Hijacking and Bombing. "Until we get more intelligent about security, we can certainly apply common sense to our screening rather than a tick box approach." Baum believes the gold standard is psychological screening. In other words, security officials should be looking for perpetrators, not just their weapons.

According to the Aviation Safety Network, an industry watchdog, almost all 50 aircraft hijackings since the September 11, 2001, attacks have been the work of lone hijackers who pretended to be armed—something conventional security screening has no way of detecting.

"There is a big debate over profiling of race and nationality" in screening, says security expert Jeff Price of the Department of Aviation and Aerospace Science at Denver's Metropolitan State University. "But the behavioral side of profiling has a strong basis. There should be a layer of security questioning in all areas of aviation security. Customs agents and police have been doing it for years. They might have stopped this guy if he displayed some odd behavior."

"Passengers' behavior at security checkpoints are what we always record," says Baum, "but people are at their most nervous then because we give them a series of specific things to do, like taking off shoes and removing laptops. It's more revealing what they do before and after the checkpoint. Air crew should be trained in psychological techniques."

The best in the profiling business is, by many accounts, Israeli state airline El Al. In 1986, Anne-Marie Murphy, a young Irish woman who was pregnant, was prevented from boarding an Israel-bound El Al flight from London because security officials flagged the unusual profile of a pregnant woman traveling alone. Her bags, which had passed through airport screening, were found to contain a bomb. (Murphy claimed ignorance and was acquitted, but her Jordanian fiancé, Nezar Hindawi, was jailed for 45 years by a British court.)

So why don't all airports use such proven methods as passenger profiling and behavior analysis? "Regulators don't like subjective security processes," says Baum. "They worry about the political fallout of extra screening based on race, religion and gender. And it's hard to quantify; you can test X-ray screeners, but it's much harder to test psychological screeners."

After the Metrojet attack, another category of person operating within an airport's perimeter was shown to be a threat: the airport insider who smuggles arms or explosives on a flight. "We need better, more effective background checks" on airport staff, says Price. "Tracking social media use, assigning a risk score. It's not a perfect solution. But that way, we know who to watch."

Following the Metrojet tragedy, Russia, Germany and Britain sent experts to ensure that airports in Egypt implemented security improvements. "If all these changes are put in place on a continuous basis, this would make Egyptian airports among the safest in the world," says Angus Blair, president of the Signet Institute, a Cairo-based think tank. And EgyptAir co-pilot el-Kaddah confirmed that Egyptian aviation security has tightened up since the Sinai crash.

"Even the high ranks get searched, even friends get searched, even captains get searched," says el-Kaddah. "Things are getting tougher, and security is working properly. It's more searches than in history."

When he first heard that a bomb-wielding maniac was on board his plane, el-Kaddah was furious at airport security. "I was angry about it at first and frustrated, and I thought, What are they doing? They are just giving us a headache," he says. "Then I found that it was a fake. [So] you can't blame them because he pretended. It looks like a real bomb, but it is not."

Even if the Alexandria security screeners weren't at fault, the hijacking dealt another blow to Egypt's reputation among tourists. Before the Metrojet attack, tourism accounted for 11.3 percent of the country's gross domestic product. And although Rasha Azazy, director of the Egyptian Tourist Board in London, insists that the latest hijacking would have "no effect" on tourism, once-teeming resort hotels in the Egyptian city of Sharm-el-Sheikh have reported a shortfall of over 1 million tourists from last year's numbers. Last month, a major tourism convention, Internationale Tourismus Börse in Berlin, left Egypt off its list of "Top 50 countries to visit"—even though Egypt was the convention's Jubilee Cultural Sponsor.

Unfair it may be, but Egypt's economy stands to be decimated by collapsing confidence in the country's ability to keep visitors and its citizens safe. "They're doing their best," says Amgad el-Gabbas, a political researcher, as he waited to meet his sister-in-law Dalia Saad at Cairo's gleaming airport. Saad had been on the hijacked flight. "It could happen in any airport in the world."

The chilling lesson of the Cyprus hijacking is that el-Gabbas is right. As long as security procedures screen objects and not people, all aircraft are vulnerable to the actions of the mad and the desperate.

With reporting by Ruth Michaelson.