A fragment of a cometary building block has been found inside a meteorite that broke away from an asteroid. The rare discovery provides a critical insight into the formation of the solar system over 4.5 billion years ago, and how it evolved into what we see today.

When the sun first formed, it is believed to have had a cloud of gas and dust. Gravitational forces clumped much of this together to form the planets. The rest made up the moons, dwarf planets, asteroids and comets. The difference between the latter two relates to composition—asteroids tend to be made of metal and rock while comets are made up of ice, dust and rocky material. Comets are normally found farther away from the sun, in the colder parts of the solar system.

Meteorites are bits of asteroid that have broken apart from their parent body during collisions in space, which then survive the journey through the Earth's atmosphere and smash into the planet's surface. Because meteorites are largely unchanged since their formation, studying them allows scientists to understand what these early conditions were like when the solar system was created.

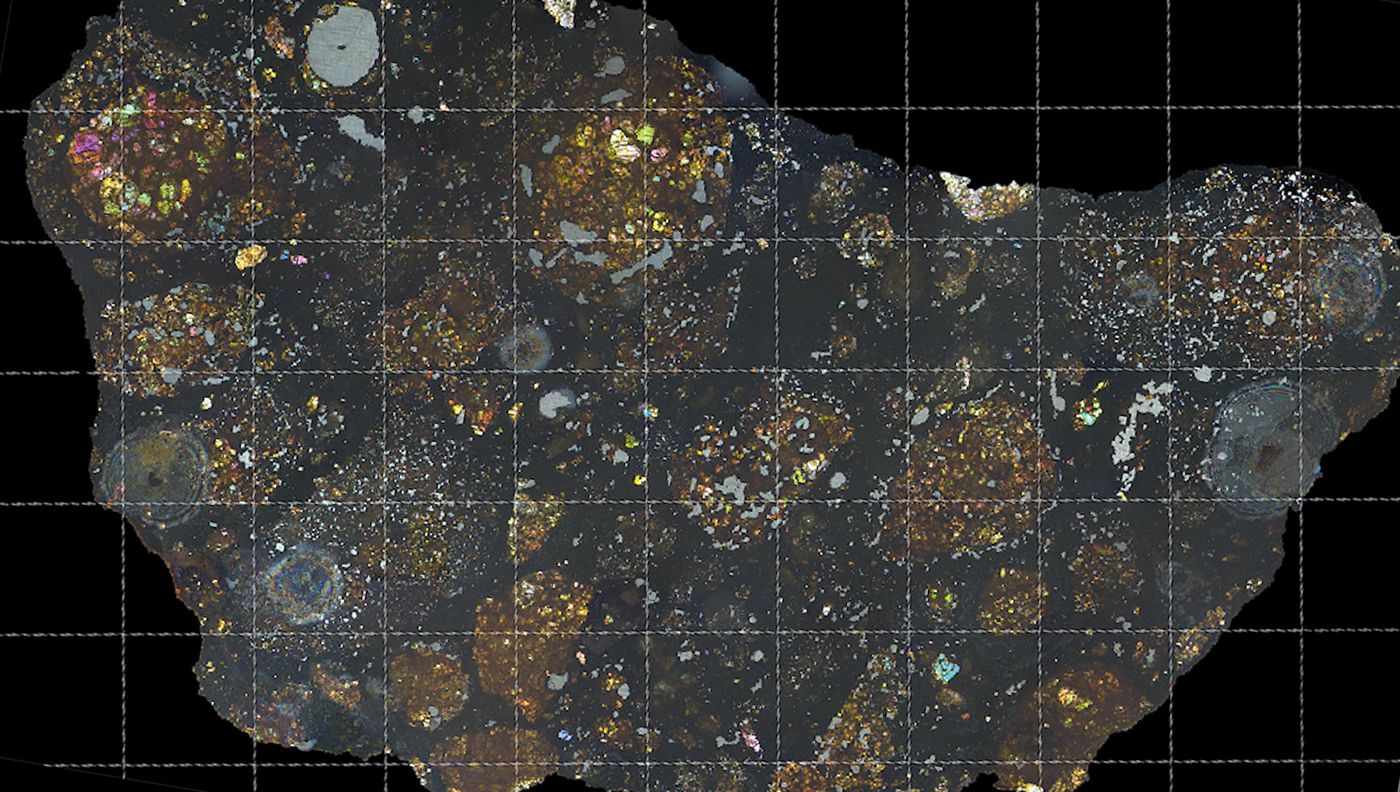

In a study published in Nature Astronomy, scientists were analyzing a meteorite called LaPaz Icefield 02342, which was found in Antarctica in 2002. It is a type of primitive "carbonaceous chondrite" meteorite that formed about 3.5 million years ago, just beyond Jupiter.

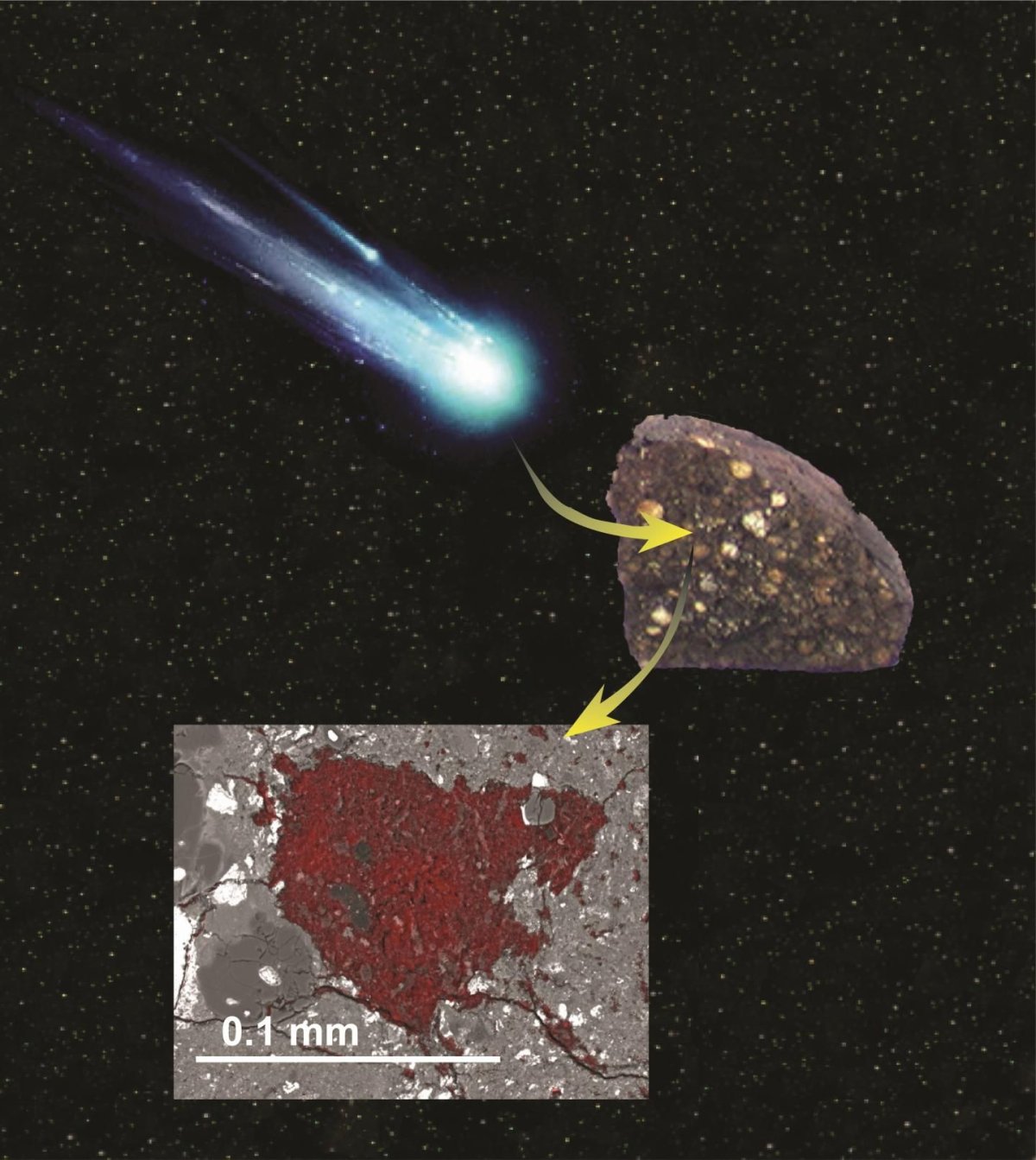

The team, led by Larry Nittler from the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington D.C., was examining the meteorite when—completely by accident—they found a tiny section that appeared to be a comet's building block. This would mean a bit of space dust that originated from comets forming at the edges of the solar system somehow got captured and encased by an asteroid.

"I knew we were looking at something very rare. It was one of those exciting moments you live for as a scientist," said study co-author Jemma Davidson of Arizona State University in a statement.

Nittler said: "Because this sample of cometary building block material was swallowed by an asteroid and preserved inside this meteorite, it was protected from the ravages of entering Earth's atmosphere. It gave us a peek at material that would not have survived to reach our planet's surface on its own, helping us to understand the early solar system's chemistry."

The team believes its findings suggest that primitive cometary material at the solar system's edge migrated inward, providing new insight into how material was moving around the solar system before the Earth had fully formed.

Nittler told Newsweek: "It helps us understand a bit better how material came together to form the planets when the solar system was a giant rotating disk of gas and dust around the forming Sun. It tells us that as carbon-rich icy bodies were forming in the far outer reaches of the disk, some of their building blocks moved closer to the Sun and got trapped in asteroids. Also, because the fragment was trapped in the meteorite some of its more fragile chemical signatures ere better preserved than when we find comet dust directly hitting the Earth, allowing us a better understanding at how these materials formed and were distributed in the disk."

Romain Tartèse of the U.K.'s University of Manchester, who studies meteorites but who was not involved in the latest research, said the discovery was exciting because it provides evidence that material was being transported inward for millions of years after the solar system first formed.

"[The researchers] very convincingly suggest that this clast is indeed a remnant of an icy cometary body accreted in the outer solar system where Kuiper Belt objects formed," he told Newsweek. "These findings have crucial implications regarding transport of material in the solar system."

Matthew Genge of Imperial College London, who was also not involved in the study, said the findings are important because comets and asteroids are believed to have delivered the ingredients required for life on Earth to emerge. "One thing we know about asteroids and comets is they both can contain water and organic materials. It is thought that much of our planet's water and carbon was added by them, crucially just before life appeared around 4 billion years ago," he told Newsweek.

"What this study tells us is comets and asteroids mix," he continued. "A bit like tigers and lions, this tiny piece of comet in an asteroid suggests there are lions with stripes, or tigers with manes—objects that consist of both comets and asteroids. It also tells us that, like tigers and lions, they both must have been in the same place. Comets formed in the outer solar system, but at least one escaped and reached the asteroid belt in the early history [of the] solar system."

This article has been updated to include quotes from Larry Nittler.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Hannah Osborne is Nesweek's Science Editor, based in London, UK. Hannah joined Newsweek in 2017 from IBTimes UK. She is ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.