Ever since she was a young girl growing up in the rough suburbs of Mexico City, Citlalli Hernández had big political dreams. "I always thought that something was wrong with the country, that I had to do something to transform it," says the 28-year-old. "I wanted to be the first woman president."

In a country that ranks 81st in the world for gender equality, according to the World Economic Forum, such ambitions have been far-flung: When Hernández was growing up in the early '90s, women held just 8.4 percent of seats in the lower house and 4.7 percent in the Senate. "In Mexico, it's still hard for people to understand that women can have power," she says. "Unfortunately, in politics, men have always had greater opportunities."

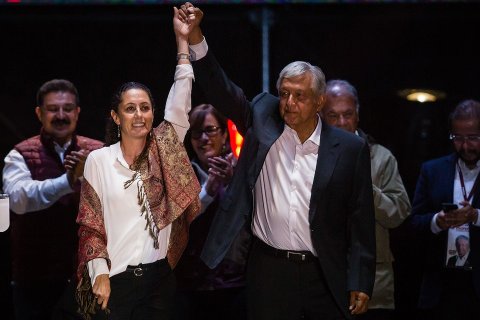

But Hernández was undeterred. In 2014, she joined Morena, a political party newly founded by a fiery leftist with presidential aspirations of his own: Andrés Manuel López Obrador. A year later, she ran for a seat in Mexico City's local congress and won. Then, on July 1, alongside the presidental victory of López Obrador, Hernández became the youngest person elected to the Senate in the country's history.

Her win was part of a political revolution for women in Mexico. That night, Mexico City voters also elected a woman, Claudia Sheinbaum, as their next mayor, arguably the second-most important elected position in the country. Women also won enough seats to make up half of most state houses. But the big achievement was the national legislature: When Hernández took her seat in the Senate on September 1, she was one of over 300 women entering Congress, meaning that, for the first time ever, there would be nearly total gender equality in both houses.

As a result, Mexico ranks fourth in the world for women's legislative representation; by contrast, the U.S. ranks 102nd, with only 23 women serving in the U.S. Senate and 84 in the House of Representatives, making up less than 20 percent of the lower chamber's members. "It's a historic opportunity to advance the rights of women," says Hernández. "That's why it falls on us to spread the example and inspire many more women to break cultural biases."

The sweep could have far-reaching implications for everything from workplace protections to abortion rights to the country's gender pay gap. And female legislators seem to have an enthusiastic ally in López Obrador; for the first time, there will be gender parity in the presidential Cabinet, with women set to head key departments, such as economy, energy and labor, when he takes office on December 1.

Among them is former supreme court justice Olga Sánchez Cordero, the incoming secretary of government, one of the most powerful roles in the next administration. During the campaign, she promoted a document known as "Femsplaining" that offered solutions to tackle the most pressing problems facing women in Mexico, including domestic violence, workplace abuse and underemployment. She has even vowed to decriminalize abortion once López Obrador is in power. "We're going to change this patriarchal system into a system of family democracy," Sánchez Cordero said with a shake of her fist at a recent press conference. "That is my project."

Implementing these proposals won't be easy. Mexico remains a mostly conservative Catholic country, and abortion is illegal in 17 of its 32 states. Even more problematic is a historic cultural hostility toward women that often ends in violence. The country is in the grips of a femicide epidemic, where women are killed specifically because of their gender. In 2017, 3,256 women were murdered across the country, up from 2,790 the year before.

"This violence is the result of social, cultural practices and policies that endorse, that tolerate the aggressive behavior of men," says Georgina Cárdenas, a gender studies expert at Mexico's National Autonomous University. "Machismo in this country is killing us."

Having more women in office is an important first step in changing both the social attitudes and legal frameworks that lead to violence, says Cárdenas: "Symbolically, it's seen that of course women have the same capabilities as men to be in positions of power. And it's often these same women who promote agendas in favor of gender equality."'

For women in Mexico, who won the right to vote 65 years ago, gender parity has been a long time coming. But unlike the wave of women currently running for office in the U.S., which was spurred by anti-Trump activism and the #MeToo movement, this new class of Mexican politicians is the result of government reforms designed to upend a power structure that has locked women out of public life. "The feminist movement in Mexico has spent years asking for this," says Araceli Damián, a Mexican congresswoman who is also part of López Obrador's Morena party.

The process began in earnest in 2003, when Mexico implemented a 30 percent quota for female candidates on ballot papers (in Mexico, parties decide who runs for office, not individual candidates). At the time, women held just 17 percent of seats in the lower house. The quota was then raised to 40 percent in the 2009 elections.

But according to Damián, power brokers in major parties found ways to cheat the system, running female candidates in districts where they were likely to lose. If they won, officials would push them to resign and replace them with men.

Significant change didn't come until 2011, when a major court decision required parties to fully comply with the gender quota. Three years later, an amendment to the Mexican Constitution mandated an equal number of men and women candidates in federal and state legislatures. "The rules have been written to make sure that the cheating that went on won't work," says Magda Hinojosa, an associate professor of political science at Arizona State University, who has followed Mexico's gender parity laws closely. "It will cement the tremendous gains that women have made—gains that won't be reversed."

The steady increase of women in politics is having a significant impact on Mexican law: According to a 2014 study by Jennifer Piscopo, assistant professor of politics at Occidental College, "female legislators introduce the vast majority of women's interest bills…[which] overwhelmingly promote feminist, progressive visions of women's rights and roles."

At a September 6 press conference in Mexico City, newly elected female senators from all parties gathered to announce a plan to reform 15 articles of the Mexican Constitution to extend the gender parity mandate to the executive and judicial branches. Senator Kenia López said the proposal would help "eliminate discrimination, exclusion, abuse, violence and the constant risk of violation of women's rights and fundamental freedoms."

But perhaps more important, says Hinojosa, is how this increased representation may shift Mexican culture and society more broadly. "Seeing women in office brings about tremendous social change," she says. "It sends a message that women are valued, that women absolutely belong in politics and everywhere else."

Challenges remain, including opposition from other women. Of particular concern for abortion activists: The rise of the conservative Social Encounter Party, a hard-right evangelical group that saw a boost in the last election due to an alliance with the Morena party.

For the new crop of female politicians, however, the greatest worry remains the femicide epidemic and the impunity that runs rampant in Mexico's criminal justice system, disproportionately affecting women. A 2013 study from the National Citizen Femicide Observatory found that only 1.6 percent of murder cases investigated as femicides in Mexico end in sentencing. "It's the big moment," says Hernández, the young senator, who is too focused on her new job to entertain the idea of running for president one day.

But the reality of a woman president? Of that Hernández has no doubt. "I think it will come a lot sooner than we think."

Correction: A previous version of this story mistakenly stated that the study from Jennifer Piscopo was published by the University of California, San Diego in 2011. The piece has been updated to reflect that it was published by the author herself in 2014.