Millions of mice are used in scientific research every year in all manner of experiments, many of which involve genetic manipulation. So perhaps the news that two teams of scientists have accidentally created mice with both unusually long and short tails during their investigations shouldn't come as a surprise.

According to separate papers published in the journal Developmental Cell, a gene known as LIN28B—which influences characteristics such as metabolism and body size—was responsible for the strange outcome.

Read more: These monster mice are eating rare seabird chicks alive in an "environmental catastrophe"

"The same regulatory networks that control mechanisms regulating how a body pattern is formed are often co-opted for other developmental processes," Moisés Mallo, a researcher at Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência in Lisbon, Portugal, and senior author of one of the two papers, said in a statement. "Studying these networks can give us relevant information for understanding other developmental processes."

One of the teams was trying to model kidney tumors by controlling the gene expression—the process by which genetic code is used to direct the production of proteins or other molecules—of LIN28B.

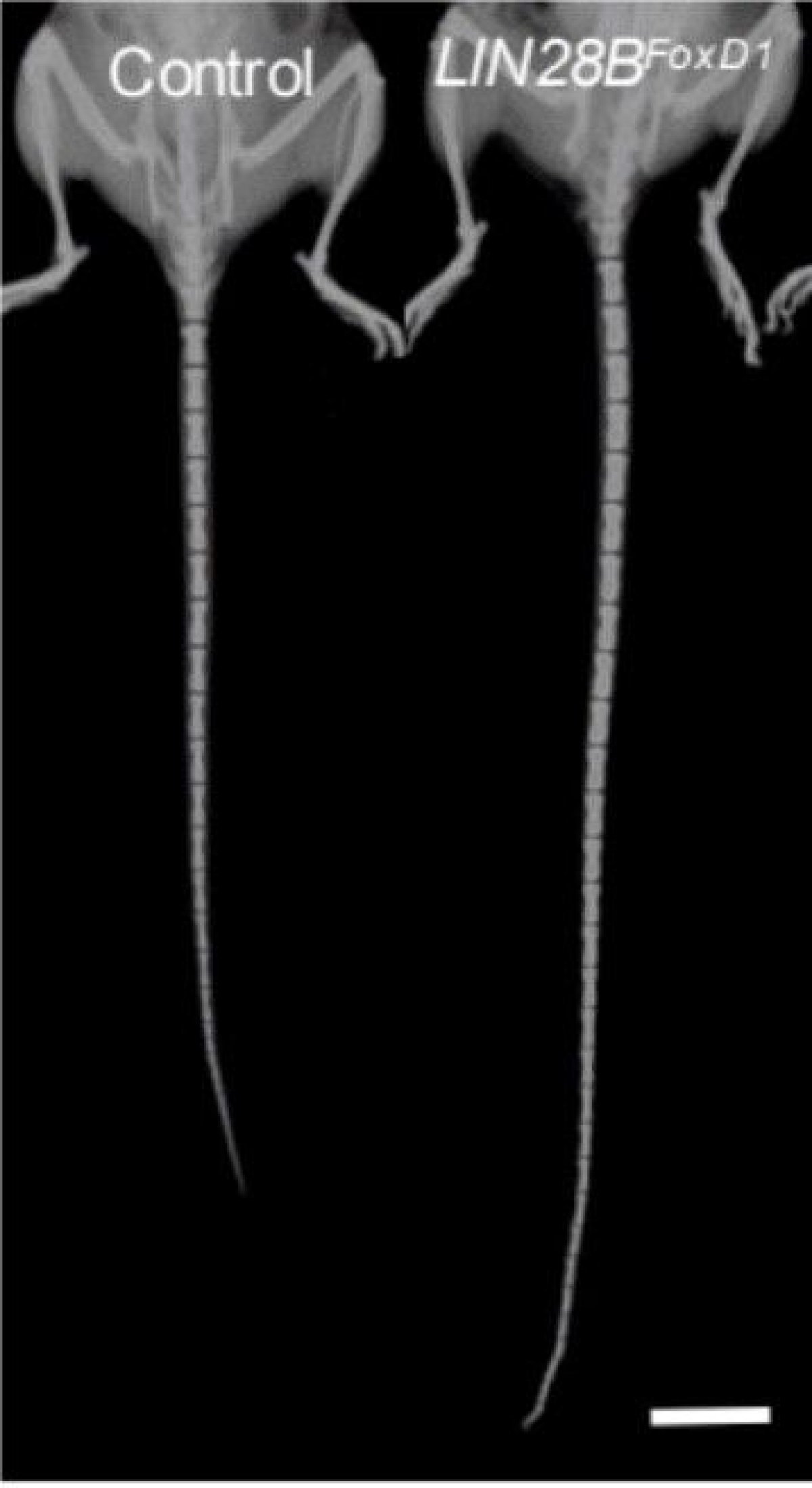

"What we found was that the animals with this gene over-expressed had remarkably long tails," Daisy Robinton, an author of one of the studies from Harvard, told Newsweek. "So long, in fact, that we didn't even need to genotype them to know that they had this gene turned on—it was so dramatic."

"The group found it to be a delightful unexpected result," she said. "We realized how fundamentally important the work was, as no result like this had ever been described anywhere in the animal kingdom."

The other team, meanwhile—led by Mallo—were investigating a gene called GDF11, which scientists know triggers the development of the tail in the embryo. They noticed that mice with mutations in this gene had shorter and thicker tails than normal mice, while also finding that LIN28B had an important influence on this process.

Essentially, LIN28B regulates the timing of how certain blocks of cells—which become skin, muscle, cartilage, tendons, and vertebrae—develop in the embryo, thus affecting the shape of the tail.

"There are also important implications in this research for understanding evolution," Robinton, said. "Natural selection has created a variety of tail lengths to suit different evolutionary pressures. Until now, little was known about how length is controlled and how the manipulation of genetics can impact morphogenesis [the biological process that creates the shape of an organism.]"

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.