The World Health Organization has taken aim at the myth that migrants and refugees bring diseases to the countries they arrive in, with its first report on migrant and refugee health in the European region. In the report, the WHO dispels the falsehood that irregular migrants and refugees spread sickness among host communities—an argument that has long been used to justify anti-immigration views and policies.

According to the WHO's findings, which were based on a review of more than 13,000 documents, "There are indications that there is a very low risk of transmitting communicable diseases from the refugee and migrant population to the host population.

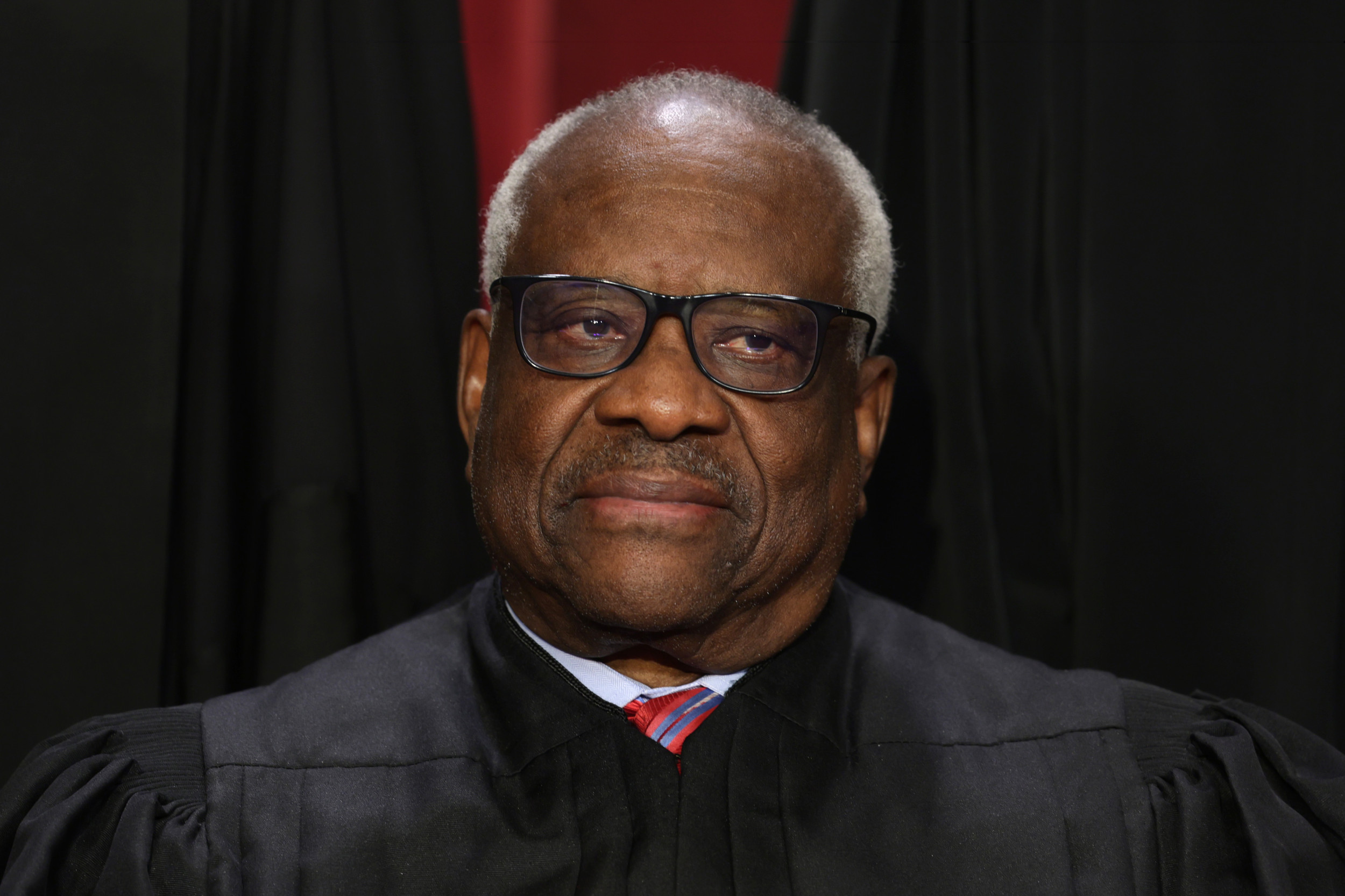

Related: Donald Trump claims migrants bring 'large-scale crime and disease' to America

In a statement on the report shared on the United Nations website, Dr. Zsuzsanna Jakab, WHO regional director for Europe, said, "The refugees and migrants that come to Europe, they do not bring any exotic diseases with them—any exotic communicable diseases.

"The diseases that they might have there are all well-established diseases in Europe, and also we have very good prevention and control programs for these diseases. This applies both for tuberculosis, but also HIV/AIDS."

While the new WHO report is focused on migrant and refugee health in Europe, its message is relevant to the U.S., particularly in light of President Donald Trump's repeated claims that migrants bring "large-scale crime and disease" to the country.

Late last year, Trump used the claim to rail against Democrats for wanting "open borders for anyone to come in" to the U.S., which he claimed would bring "large-scale crime and disease" into the country.

While the WHO's study, which covers 53 countries in the organization's "European region," did not find evidence of increased transmission of diseases between migrants and refugees and those living in the countries they arrive in, it did say that migrants and refugees are themselves at greater risk of developing diseases during the migration process.

Citing data from the United Nations' International Organization for Migration, the report notes that more than 50,000 migrants and refugees have died in the Mediterranean area since 2000, which has significant "health repercussions" on surviving family members and communities.

"The social determinants of health will act along the displacement and migration continuum…and societal conditions are significant factors in the health and well-being of refugees, migrants and communities," the report states. "Many of these factors lie outside the direct influence of the health sector."

The report adds, "As a consequence, the conditions encountered during their journey, as well as the living, working and aging conditions at their destination, can have negative health repercussions for many refugees and migrants."

The report also asserts that a number of diseases appear to affect refugees and migrants more than host communities, including diabetes, which researchers found affects refugees and migrants with "higher incidence, prevalence and mortality rate," particularly among women.

The study also found that while displaced populations are at a lower risk of all forms of cancer, except for cervical cancer, they are more likely to be diagnosed with the disease at a more "advanced state," putting them at greater risk of "considerably worse health outcomes than those of the host population."

The report also says that other illnesses, such as depression and anxiety, tend to affect refugees and migrants more than the communities in the European countries they arrive in. That finding, researchers said, is particularly applicable to unaccompanied minors who the study found suffer from higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder.

The WHO also highlighted the challenges that undocumented immigrants around the world face in obtaining access to health care services.

"I don't think that in most of the countries the illegal migrants have access to the health system services," Jakab said. "So that is an area where we have to do substantial additional work and conviction of the countries, because, the best way to protect their own population and the refugees is to give them access."

In addition to dispelling myths concerning the health of migrants and refugees, the WHO's report demonstrated how perceptions of a rise in the number of migrants and refugees arriving in Europe have been overinflated in some countries.

"International migrants make up about 10 percent of the population in the European region. That is about 90 million," Jakab said. "Out of this, less than 7.4 percent are refugees, and in some of the European countries, citizens estimate that there are three or four times more migrants than there are in reality."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Chantal Da Silva is Chief Correspondent at Newsweek, with a focus on immigration and human rights. She is a Canadian-British journalist whose work ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.