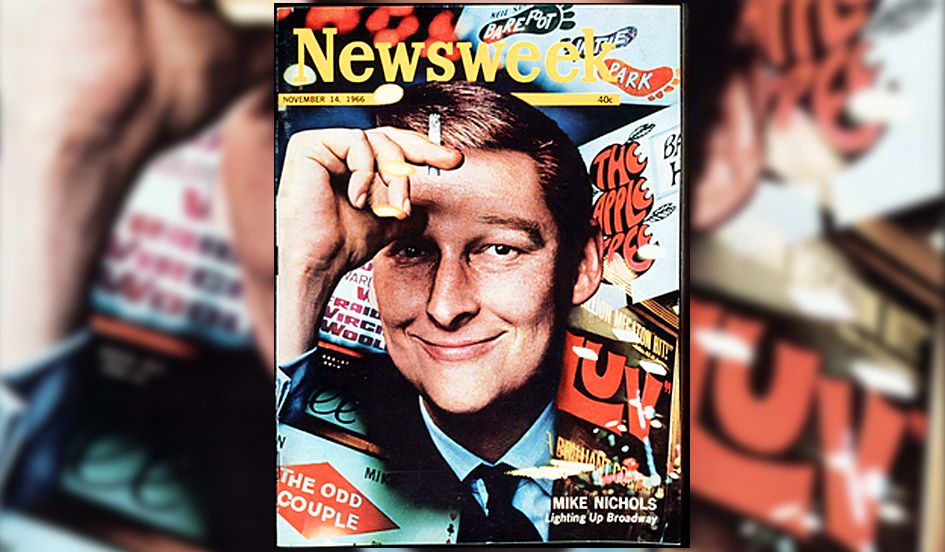

Celebrated director Mike Nichols, known for movies such as The Graduate, The Odd Couple, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and a number of Broadway hits, died Wednesday at age 83. In a 1966 interview with Newsweek, Nichols, then 35, spoke about discovering directing, feeling like a fraud despite his overwhelming success and his next project, a movie called The Graduate, which would go on to win him an Oscar.

When Mike Nichols came to America in 1939 at the age of 7, as a refugee from Nazi Germany, he could speak only two sentences in English: "I do not speak English" and "Do not kiss me." From there on, he improvised.

Today, at 35, he has improvised his way into a spectacular double success, as a celebrated satiric comedian (in partnership with Elaine May) and as America's highest-paid, most sought-after director, its only star director of the moment. With four hits running simultaneously on Broadway – "Barefoot in the Park," "Luv," "The Odd Couple" and his new "The Apple Tree" – as well as the movie hit of the year, "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?", Nichols has more marquees lit up than producer David Merrick. In fact, between them, they run Broadway.

In a world where a playwright's or a star's name is no assurance of commercial success, director Mike Nichols sells tickets. Before "The Apple Tree" opened on Broadway, the "new Mike Nichols show," the "first Mike Nichols musical," had a million-dollar advance, and since it opened – to mixed reviews – it has been selling out almost every performance. Partially, of course, it is a testament to the versatility and charm of Barbara Harris, but Nichols also gets star billing.

Nichols today is one of those absolute American success stories – a fellow who is recompensed enormously for being himself. He is under a retainer to CBS, at a substantial (and unquoted) figure, to do whatever, whenever, he wants on network television. Recently he was named movie director of the year by the National Association of Theatre Owners. "I sleep a little better every night knowing that Jack Valenti is my president," he said as he accepted the awards.) He can call his own shots on Broadway and in Hollywood. Says his agent, Robert Lantz: "In the beginning he was a comedian, and they said, 'Let's give him a comedy.' But now he's done a serious movie and a musical. All the barriers have fallen. He's being offered everything from the stock-exchange report to the sports pages."

Conspiracy: But Nichols' success cannot be measured in dollars and offers alone. He has brought freshness, fun and excitement to a dreary and predictable Broadway. And ex-actor Nichols has made stars out of such new types as Alan Arkin ("Luv") and veteran Walter Matthau ("The Odd Couple"). Critic Susan Sontag says, "To me the direction of the actors in 'Virginia Woolf' is brilliant. Elizabeth Taylor gave the best performance of her life. She's a real actress. If someone has the capacity, Mike can get it out of them." A director's chief virtue should be to persuade you through a role," says Richard Burton. "Mike's the only one I know who can do it. He conspires with you to get your best. He'd make me throw away a line where I'd have hit it hard. I've seen the film ['Virginia Woolf'] with an audience, and he was right every time. I didn't think I could learn anything about comedy – I'd done all of Shakespeare's. Bur from him I learned."

Playwrights also learn from him. "People who work with Mike are spoiled for all time," says Neil Simon, "because he is the best, the brightest, the strongest, and I'ts never as much fun with anyone else." "He's a good director," says Edward Albee with characteristic restraint. "There are very few good directors. Only about two and a half."

That makes Nichols almost half the supply of good directors and therefore he is a rich one – he received a quarter of a million dollar salary for "Virginia Woolf" and he gets a healthy cut of the take from all his shows. He lives in an elegant triplex terrace tower apartment overlooking all of New York City. In his living room are pictures by Matisse, Picasso, Rousseau and, over the fireplace, a tiny little Vuillard, which is lit by a sound switch at a handclap.

He has a butler to serve the right wine with every meal, and a chauffeur to transport him in a Lincoln Continental. Separated from his second wife, he has a beautiful 2½ -year-old daughter named Daisy. He even has a horse of his own, an Arabian named Nancy. Among his close friends are the most important people in several worlds, including Jacqueline Kennedy, the André Previns, the Richard Avedons, the Leonard Bernsteins, Julie Andrews, Penelope Gilliatt, the Alan Arkins, Ulu Grosbard. Yes, but in the worlds of Passionella, the chimney-sweep who becomes a movie star in "The Apple Tree," is he "truly content"?

Ambivalence: Coming out ot "The Apple Tree" after a recent performance, Nichols heard someone say, "Big deal Mike Nichols, what's so hot about him?" Feigning deafness, he walked on, and said later, "There's no way to let them know I don't think I'm a big deal. I can't turn around and say, 'I agree with you'." Nor, for that matter, can he turn around and say, "I am so a big deal." Nichols is torn by a curious ambivalence, a feeling "of terrible arrogance and self-deprecation, at the same time. I'm doing it better than anyone and I can't do it at all. I'm a fraud."

Nichols has the great grace of laughter, and one of his favorite laugh-objects is himself. Sitting one evening in a Hollywood restaurant, a waitress told him: "Those people over there just have to know who you are." "Manny Gumbiner," said Nichols. "You know, 'The Manny Gumbiner Show' on television." The waitress dutifully reported the information and, as Nichols watched, the people nodded happily. Often his wit is Thurberish and bizarre. Burton recalls a dinner party at Mike's house in Hollywood. "The butler offered him the avocados and said, 'These avocados, sir, was picked from your own garden.' Mike gazed at him and said, 'That is deeply moving. I must visit that tree some time.'" And he notes with relish that there is another Mike Nichols, who co0stars "with Anna Brazzou in a Greek movie that keeps coming back to 42nd Street. I'm afraid to see it. It may be me."

One night in Sardi's, someone said to Nichols, "I understand you were born in Berlin." "Not any more," he snapped. Actually he was born in Berlin, as Michael Igor Peschkowsky, the son of a German mother and a Russian father whose patronymic was Nicholaiyevitch, later Anglicized to Nichols. His father, a doctor and the son of a doctor (Mike's only brother is a doctor at the Mayo Clinic), fled from Russia to Germany, learned German, took his medical exam, fled from Germany to America, learned English, took his medical exam, set up practice in Manhattan, then sent for his family.

Since their mother was sick (she joined them the following year), Mike and his younger brother were shipped by themselves on a boat from Germany to America, where they were met by their father. At first the two boys were boarded with patients of his on Long Island. "They were horrible English people," remembers Mike. "My brother was 3 and they shook his hand goodnight."

'Another Fake': As a youngster Mike went through a series of progressive private schools – Dalton in New York, Cherry Lawn in Darien, Conn., and Walden in New York – with no apparent success. "I didn't enjoy school very much," he says, and then lists some of the things he didn't learn. "I never had any geography of any kind and to this day I have the handwriting of an idiot," which may be one reason he is reserved about giving autographs. "Let's see his handwriting," demanded a fan recently, looked at it, then shouted, "Another fake!"

When he was 12, his father died, leaving his family with little money. Mike continued his education on scholarships. He was lonely, had few friends but remembers his enemies vividly. "There was one guy at Cherry Lawn who used to hold my head under the water. He would stand on it." When he and Elaine May were appearing at the Blue Angel, this childhood bully appeared one night and said, "You don't remember me." "It was as if I had been waiting for that moment for fifteen years," says Nichols. "I said, 'Your name is so-and-so and you were a son of bitch. What are you doing now?'" "I'm selling used cars," said the former bully. "I'm so glad," said Nichols.

By 14 he was stage-struck. "I read every word by O'Neill. At Cherry Lawn the dramatics teacher said I was intelligent and not in any suited to the theater. I think she was right." Still, "he always said his main interest was theater," recalls Lucile Kohn, who taught him Latin at Walden, "but I thought it was just a pipe dream." Miss Kohn, now 84 and retired, tells of having lunch recently with another former Walden teacher. "I asked him, 'What do you think of our most famous student?' He guessed some names. Finally I said, 'Mike Nichols.' He said, 'You don't mean that was our Mike Nichols?'"

After graduating from Walden, "I registered at NYU, and the first day they made us sing 'Oh Grim, Gray Palisades.' I got depressed and went home. I worked a year in a stable, shoveling manure, and giving riding lessons, and as a shipping clerk for Caedmon Records. I would get terrific ideas like 'Let's have Robert Frost reading his own work,' and they would say, 'Take this package to 105th Street'."

Cadavers: Finally he went to the University of Chicago, working his way through two years as a jingle judge, a night janitor in a nursery, a classic disk jockey and a post-office truck driver. "I never could find any address. Imagine a 5-ton post-office truck stopping a little old lady and asking directions."

For a while he was a pre-med, until they got to cadavers. Actually he had planned to be a psychiatrist, which, he says now, "would have been some mess." Instead, he cut most of his classes and became a campus egghead and theater person in the intense intellectual atmosphere of Robert Hutchins' university. His first bit of directing was a production of Yeats' "Purgatory."

He also acted. In "Miss Julie," he was the "lecherous, coarse butler. I was very bad. One night in the audience a dark-haired, hostile girl was staring at me. I knew she hated it and I hated her because she was right. Then Sydney Harris wrote a rave review of the play. Holding a copy of the review, I was walking down the street and I passed a friend with this hostile girl next ot him. I showed him the review and she read it over his shoulder and saidm 'Ha!' and walked away. The next time I saw her she was in the Illinois Central station sitting on a bench. I went up to her and said, in a foreign accent, 'May I sit down?' She said, 'If you vish.' We played a whole spy scene together." That was of course the world's first Mike Nichols-Elaine May skit.

Lake Michigan: Both became members of the off-campus Playwrights Theatre, which later became the Compass, an improvisational theater. "I thought, I can't do this at all," he recalls, and then found suddenly that he could. "It became mostly a pleasure because of Elaine's generosity. I loved it. You could do awful scenes, good scenes, 50 scenes, and if you really screwed up you could run down to Lake Michigan and jump in, and run back and do another scene. The process was pleasurable. We made things on the spot, together, and in front of the audience."

Three years passed. Then "the group sort of fell apart." He and Elaine struck out for St. Louis for a while, then to New York. "We never had any plans to be a comedy team or being show business or anything." But agent Jack Rollins got them an audition at the Blue Angel. They played there and at the Village Vangaurd, doing mostly their best scenes from the Compass, began appearing on television, became an overnight sensation and gave birth to a whole new kind of comedy – satiric, acerbic, situational. Spoofing anxieties and banalities in everyday life, they conjured up a hilariously diverse array of conflicting couples – first-daters, tangled up in the back seat of a car, an anguished telephone and a super-stubborn operator, a pushy mother and her put-upon scientist son. ("I feel awful," the son says after a particularly frustrating talk with his mother. "If I could only believe that," she says, "I'd be the happiest mother in the world.")

Suddenly they were rich, famous, deluged and dazzled 0 and in Hollywood about to sign up for a television series. A roomful of agents watched breathlessly as Nichols picked up the first contract, began to sign, then stopped. "I don't think I will," he said, and giggled. The agents groaned, Elaine laughed, and they flew back to New York.

'Leftover Half': After their two-man show closed on Broadway, the team broke up. "Elaine no longer enjoyed it terribly," says Mike. "Mainly she watned to write … I was the leftover half of a comedy team. I really felt for a long while that what I was able to do came from my special connection with Elaine. Without her, there was not much I could do. I was in a Slough of Despond."

He did have some acting offers. "I didn't and don't think I can act and I suffer when I act other people's words. Tyrone Guthrie asked me to play Hamlet. I said it wasn't possible." The year before, Nichols had almost played Iago, off-Broadway, to Richard Burton's Othello and Julie Andrews' Desdemona. "We had our first reading. As Richard and I read together, my voice got higher and higher, and more Mid-western. Iago became a squeaking Chicagoan. At the end, I closed the book and said, so long, everybody."

Nichols then "mooched around wondering what would happen next." What happened was an offer, for $500, to direct the Bucks County tryout of a new comedy called "Nobody Loves Me." When the author took the play home for repairs, Nichols hied himself off to Vancouver for the summer to direct "The Importance of Being Earnest" and to play the Dauphin opposite Susan Kohner's St. Joan. "That terrible summer! One day I had a fit – about Canada. I said 'Blow it up!' We don't need it. We can get our ginger ale somewhere else'."

Soon he was doing "Nobody Loves Me" on Broadway, except that now it was called "Barefoot in the Park." It was a smash hit, and Mike Nichols was a director. "Here I am," he thought, "at home, the first thing I really like. It fits." And he realized he had always been "kind of directing. I used to nag Elaine about certain things. I used to scream about the lights a lot." Wasn't it an unsettling experience? "It was a settling experience. It was a very happy time discovering directing."

'Me Too': Soon everyone was talking about the Mike Nichols touch – everyone except Mike Nichols. "The great thing about Mike is that he cuts right through the nonsense," says Buck Henry, who is collaborating with him on the screenplays of his next two movies, "The Graduate" and "Catch-22." He once asked me to tell him what 'Virginia Woolf' is about. I said, 'Well, it's about reality and illusion and the kind of games people play to fill in gaps of emptiness.' I blubbered on until I was up to my neck in theory. When I was finished he said, 'It's about a man and a woman named George and Martha who invite a young couple over for drinks after a faculty party. They drink and talk and argue for ten to twelve hours, until you get to know them'."

Nichols explains, "There's only one question the audience asks: Why are you telling me this? There has to be a good strong reason. If it's funny, that's a reason. If it's not funny, you better have a very strong other reason. The more clearly and specifically you answer this question, the more you've done your job. Whether it's poetic theater, stylistic theater, musical theater, naturalistic theater, the aim is always, in a way, to imitate life believably, to make the people in the audience say, me too, I know that."

Fun: Nichols is slavish about detail. In rehearsal, his most vehement criticism is "too general!" He works over a play, line by line, gesture by gesture, always in the hope of finding one new thing. In preparing the Adam and Even episode in "The Apple Tree," one day he asked Alan Alda, as Adam, to be a doctor, and Barbara Harris, as Eve, to be a flamenco dancer. "We improvised," says Miss Harris, "and we had fun, and then went back to the scene. It helped free us from the importance of the scene.

The sensitive, mercurial Miss Harris appreciates the fact that Nichols lets her have "private things." On the other hand, Alan Arkin says, when there was any hint of conflict or indecision in the air, he could smell it. He brings it out. None of this hiding in corners and saying, 'Why don't you try this? And don't tell the others'." The truth is that Nichols improvises his method to suit the actor. "I love to talk with Alda," he says. "I love to go into corners with Barbara, and who wouldn't? I don't go home and make a chart about who likes secrets, who likes openness." During the tryout of "barefoot," "you couldn't see Robert Redford on stage." All you could see was his forceful co-star, Elizabeth Ashley. "I told him that being on stage is like being in a battle and that the first thing you do is admit you're in a battle. That night you couldn't see Ashley. Altogether we finally balanced it out."

Does all this make Nichols kind of a psychotherapist? "It has nothing to do with their private life," he says. "It has more to do with my private life. Directing brings out the father in me – an edgy dad. Acting brings out the destructive baby in me. It's better to be worrying about other people than about myself." What this leads to is a kind of mutual trust, which is shy Nichols could tell Barbara Harris one day, "That was the worst performance I have ever seen on any stage in the world," and two days later, "That was the best performance I 've ever seen on any stage in the world." As Barbara says, "I knew that somewhere in the middle, I was all right."

Cucumber: Mostly Nichols is a collaborator, an audience, an appreciator, but unlike many directors he doesn't rely simply on his own judgment. Before he makes up his mind he tries everything, listens to everybody. "I don't know what I do," he says. Alan Arkin recalls that when he first began working on "Luv," Nichols seemed unconcerned. "I was going through the torture of the damned, and he was as calm as a cucumber." Getting madder and madder, Arkin finally stopped Nichols after the rehearsal and said," Why are you uninvolved in this experience?" But, adds Arkin, "he was involved. He has a way of speaking that avoids passion but he feels very deeply." John Kenneth Galbraith recalls watching "The Odd Couple" with him. "I was enormously struck by Mike's capacity to look at a play as though it were nothing he'd had anything to do with himself, to give a cold-blooded analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of the play and its direction. I never knew anyone else in the theater how didn't try to pretend that every catastrophic weakness was in reality a strength."

Nichols' critics argue that all he has done up to now is to make the commercial more entertaining – and more commercial. Robert Brustein thinks that "Nichols is becoming famous directing precisely the kind of spineless comedies and boneless musicals that he once would have satirized." But Susan Sontag, who knew him at the University of Chicago, says the question is "How ambitious is Mike willing to be? He's one of the few people in this country who could direct Brecht properly." Nichols says he would like to try his hand at such favorites of his as Chekhov, Pinter and Beckett, and in any case he has already proven that he is not one to be pegged by his past of by anyone's prejudgment about his future. Perhaps somewhere there is the real Mike Nichols playwright, for whom the Mike Nichols touch would be the touch of life. Or perhaps, as the brilliantly witty film sequences in "The Apple Tree" suggests, movies will turn out to be the medium that releases his best talents and energies.

In any case, the plush-lined pressures of success have left Nichols with a somewhat startled look, like a little boy suddenly transformed into a giant. But he can handle the pressure, and he loves the plush. "He says he can live on a loaf of bread," says one friend, "but he needs a staff of ten to keep the loaf of bread." He wants to be liked and he is, by people in and out of show business. He is courted by socialites and the new class of well-heeled, well-buffed culture buffs. His company manners are impeccable, and his style is enormous. He is close to many people, most of whom he doesn't' see often. Alan Arkin calls their relationship "intimacy without proximity."

"Mike wants to make it in all kinds off worlds," says one friend. "There's a dichotomy in him about wanting to b known in Jackie Kennedy's world, and a fear that it would take his energy away from something else. The danger of being fashionable bugs him." Nichols loves his lavish apartment, but says he would not feel "too terrible" if it burned down. "If your life is ruled by things, you become a thing," he insists. "The only way to save yourself Is passion. Madness, maybe." Typically he greets the morning, "Thank you, God, for Another Perfect Day," uttered in a tone of absolute despair.

Protector: All ambiguities intact, Nichols sat recently for questions. What would he like that he doesn't have? "A St. Bernard and Jane Fonda. But they're not practical in the city." Then he announced, "Movies are dreams. Plays are public events. That's a distinction, not a value judgement."

He had just seen François Truffaut's "Fahrenheit 451." "I think it's a great picture, and it has absolutely awful things in it. After I saw it, I saw to myself, forget the movies. Some friends said, you're crazy, it's not half the picture 'Virginia Woolf' is. I know they're wrong. But I'll try again. It's not modesty. I know what I've done. I think I served Edward Albee and Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton well, and did what I set out to do, which was to let 'Virginia Woolf' take place on screen. I did not intrude myself terribly. I protected Albee's idea from misunderstanding, slurring or twisting.

"It's very depressing to be described as a Success, a Maker of Hits. Not to mention names, but some people have worked for twenty years in the theater on the strength of one hit. Who wants to be a Success? That's an odd profession. I didn't know how great a man Fellini was until 'Giulietta.' A beautiful failure!" When "Virginia Woolf" opened in Hollywood, "it got terrifying raves – 'Not since "Citizen Kane".' That panicked and depressed me. When it was brought into the realm of reality with some quibbles and cavils and strong reservations, I felt good. I could breathe again."

As for his future: "I'm forming a theater. I want to start a repertory company from the other end, not with a building, but with people." As people he would like his theater, he lists Barbara Harris, Alan Arkin, Alan Alda, Robert Redford, Ulu Grosbard, Paul Sills, Elaine May, Maureen Stapleton, Larry Blyden, Sandy Dennis. Obviously many have commitments, but hopefully most will react as Barbara Harris does: "Yes," she says, "without reservations."

Projects: Nichols himself is booked up through early 1968. From now until late spring he will be busy working on his movie of Charles Webb's novel "The Graduate," which, he says, "will be partly improvised." In the fall he will probably revive Lillian Hellman's "The Little Foxes" on Broadway. And in January 1968, he is scheduled to begin filming Joseph Heller's comic masterpiece, "Catch-22," with Alan Arkin playing that heroic coward Yossarian, and many of Nichols' favorite actors (Anthony Perkins, Jack Lemmon, Henry Fonda) probably playing supporting roles.

Before going to Hollywood for "The Graduate,." Nichols flew to Berlin to see the Berliner Ensemble "because I hear that it's the greatest theater in the world." It was his first trip to Germany since he had fled in 1939. He had to change planes in Frankfurt. "There was a sign for an exhibition of model airplanes. Admission, 60 pfennigs for adults, 30 pfennigs for children and cripples. I went into a coffee shop and asked for a cup of coffee and a glass of soda. The man said, 'It is forbidden to serve soda without whiskey'." In West Berlin, he visited his birthplace, but "it wasn't there. There was a small modern apartment house. Ours was an old house. It was gone."

A Beginning: Unnerved, he finally made it to East Berlin, where he saturated himself in the Berliner Ensemble. He saw "Coriolanus," "Schweik in the Second World War." "Arturo Ui," marveled at the theater, the expansive stage, the realistic props, the low ticket prices, the hard-working actors. "They spend two hours a day in the gym. They perform seven nights a week." He mused over Brechtian theory, "which has nothing to do with theater as magic, rather with theater as bread. The theater is informed by on idea – from the usher to the last bow: theater is a dialogue between the playwright and the audience."

His head full of Brecht, he flew back to New York, then to Jamaica, where sitting in the sun he thought about Nichols. "I feel good," he said. "I wouldn't change anything in my life. It's a beginning. Now we'll find out if I can do anything." He paused, and added in a burst of joy, "Wait! You're going to see such failures, you wouldn't believe it!"

'Mike Nichols: Director as Star,' by Mel Gussow, was Newsweek's cover story for its November 14, 1966 issue.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.