One by one they give in. At first the women look almost bored, but then they too become animated and are drawn into the violence. It is the second fight of the night and Andy from Newcastle is the object of their attention. "Come on, Andy!" they call to the modestly-sized man with the sculpted figure, known as The Little Axe. On his front, above the six pack, are two large tattoos. On his side is a quotation from Theodore Roosevelt, a call to action that he'd liked enough to have all 140 words inscribed down the left of his torso:

"It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood . . ."

The Little Axe isn't doing well. In fact, if anyone needs reassurance from Roosevelt – if he fails, at least he fails while daring greatly, it says just above his waist – it is 25-year-old Andy Ogle. His evening began with a flying kick from his opponent seconds after the fight started. The kick missed his head but the statement of intent it represented didn't. Ogle's rival, a Venezuelan called Maximo Blanco, then jumped on him and Ogle spent the next 25 seconds in a condition known as ground-and-pound – "ground" because you are crawling around on it trying to defend yourself, "pound" because a wrestler with a mean expression, having got you there, is trying to beat you into unconsciousness.

Ogle's face is bloodied. You can see how this is going to end. The dragon on his back is tattooed to the man who is about to lose.

"The only thing that separates me from a guy in a nine-to-five job is that I have went out and am trying to live my dream of making a living with my fists," he had written earlier on fightstorepro.com. Now his dream is coming true before 8,000 people in Berlin, all seemingly shouting for him. A man who has to stretch out the money between fights says he is "just barely skimming it" and "showing what a Geordie boy with pure grit and determination can achieve."

Somehow, Ogle finds the resources to get up. He gets an arm around Blanco's neck to try to stop the air reaching his lungs and the blood getting to his brain. It's a tired effort, though, and soon he is being pounded again.

SPORT'S NEW STAR

We are in Berlin for Fight Night 41 in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC), which is the biggest promoter in mixed martial arts (MMA). It is a phenomenon within a phenomenon. For footballers; now, even in a World Cup year, they are as likely to fix on MMA, which combines boxing, jiu jitsu, judo, kickboxing and other forms of combat into a clash of gladiators. UFC, MMA's premier organisation, has become the fastest-growing promotion company in the world according to its data, which shows annual event attendance increased twelvefold from 2001 to 2013.

Go to the supermarket – in Britain at least – and you will find two costly video games side by side. One is Fifa, capturing the swirl around the World Cup. The other is UFC. From Brazil to Canada and from Britain as far east as Japan, mixed martial arts has gone from an often seedy fringe event, to business-case study in just over a decade. By some measures it now exceeds Premier League football in worldwide popularity.

As the sport's best-known promoter, UFC reaches about 1.4 billion television viewers in 150 countries. The organisation's value has risen a thousandfold since 2001 when the Fertitta brothers bought UFC for $2m, making it worth more than two great football clubs, Real Madrid and Manchester United combined.

Its appeal is sometimes a mystery even to its executives. Where did the women come from, for example? About four in ten of the fans are female, which is not what anyone expected. "It gathers more pairs of eyeballs than the Premier League across the globe," says Dr Rogan Taylor, an expert on the football business at the University of Liverpool. "But, unlike football, MMA has a very brief history in terms of its modern form. It appears to have risen up from nowhere."

Football and MMA – the world's most popular televised sports. One a team game, the other for individuals with multiple skills, who create a team within themselves. Two versions of human endeavour, speaking to an argument as old as humanity itself. Are we co-operative beings or ruthless competitors? One sport embodies sacrifice for the sake of the group, the other a quest for individual perfection. To understand the ascent of MMA is to gain a small insight into 21st-century humanity.

HUMAN COCKFIGHTING

At first, the idea of mixing the martial arts was simply to test their power, as if the sport were designed by a seven-year-old. What would happen if a karate guy met a kung-fu guy? Who would win out of a boxer built like a gorilla and a little jiu-jitsu specialist? It evolved into a contest in which athletes, each stronger in some disciplines than others since they all take years to learn, strive to impose the strategy that favours them.

"The art is very difficult to master," says Mark Muñoz, an American of Filipino origin who headlined the event in Berlin, "because there are so many martial arts involved." They include aikido, performed by blending with the motion of an attacker before redirecting the energy of the attack against the assailant, Greco-Roman wrestling, a way of grappling that was developed during the Napoleonic wars, and taekwondo, a Korean style known for flashy kicking techniques. Muñoz might be known as the wrecking machine for his relentless ground-and-pound, but he is vulnerable to being knocked out when an opponent is still standing up, where he is weaker.

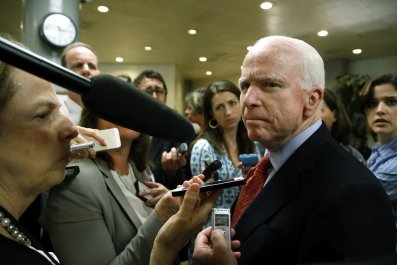

If it looks violent, it is not as brutal as its reputation. "Human cockfighting," US senator John McCain, a former amateur boxer, called MMA during a campaign to get it banned from cable television 20 years ago. For years, it was known as no-holds-barred fighting, then as cage fighting. It has an image of extreme violence. Germany was uncertain it wanted to host an event at all, while in New York state, professional MMA is banned.

Faced with McCain's challenge, however, the sport changed long ago. Now "ultimate" fighting is the health-and-safety version of cage fights. Many encounters are decided by judges as the contestants remain fully functioning mammals at the end. Others are halted early – sometimes very early – when the risk to a competitor is deemed too great.

Eye gouging is a foul. You cannot put a finger into any orifice, cut or laceration. Groin attacks are out, as is grabbing the windpipe or stomping a grounded rival. One is not allowed to kick at the kidney with a heel or even to claw, pinch or twist flesh, as many small people do in the playground. In fact, rule No 22 forbids any unsportsmanlike conduct that causes injury. Cockfighting is never as well policed.

FIGHTER-PHILOSOPHERS

Part of the appeal is that being as skinny as Popeye before eating his spinach is not a huge disadvantage: the sport evolves fastest when scrawny fighters need new moves. In the 20th century, MMA was dominated by a Brazilian family with a habit of producing at least one skinny boy in each generation who needed impeccable technique to meet brute force.

"I have more strength in my little finger than you do in your hand," the late Hélio Gracie once told a filmmaker. "Depends on the position of your hand and the position of my finger. Every aggression, whatever it is, between the beginning and the end has a space in time where we're weaker. I get everybody in that space."

This is a thoughtful violence. The fighter-philosopher is surprisingly common. The athletes, who think several moves ahead and know that any mistake has consequences, call it human chess, with limbs as pieces. For the muscled and the weak, the appeal is the same. "It's extraordinary! It's chess – it's a science," exclaimed Bob Anderson, an American wrestler who was shown the moves in the 1970s.

The result is one of the less likely business stories of the millennium. "I've been doing this for 11 years," says Ashleigh Grimshaw, a fighter who teaches MMA at the Urban Kings gym in London. "I've seen it from when it was in nightclubs, held in boxing rings, and had people smoking behind the cage. You just had a fight, and if you were lucky you got paid.

"You see kids nowadays training twice a day to try to make it. They're dedicated. Remember how you wanted to be a footballer? Now people want to be an MMA fighter. It's basically the best fight sport in the world, because there's so many ways to win."

Safe is not the same as tame: in Berlin, a contestant who broke his hand in the first round simply fought on. Others were so exhausted they could barely acknowledge the crowd. At the news conference afterwards, one fighter, stitched in both eyes, was aching in so many places he needed the same care in victory as you would use to congratulate the survivor of a fire for having only third-degree burns.

THE OWNERS

Pay for the fighters is not keeping pace with boxing or football – the top earner has scored about $700,000 so far in 2014, although a few superstars can get $5m just for turning up – but then, the breakthrough is recent. Growth has been so swift that most Europeans are still unaware an Ultimate Fighting Championship exists: depending on where you live, there's an 85-90% chance your introduction to it has come in the past five minutes. Most newspapers do not yet cover it, but the feature stories explaining MMA will come.

The story goes back to 1914, when a Japanese judo champion migrated to Latin America. He transformed jiu jitsu in Brazil, which in turn became the foundation for mixed martial arts.

The rest of the century belongs to the Gracies. Their version of jiu jitsu went around the globe. So did boxing, which broke through every cultural barrier with Muhammad Ali. It didn't last, however. Boxing seized the imagination then retreated to its fan base. The promoters of MMA hope to avoid the same fate.

And they are characters, the people who run MMA – or rather, who control UFC, the best-known league within it. At first, Newsweek wasn't allowed near Dana White, the blunt, conflicted 45-year-old who runs UFC on behalf of two Sicilian-American brothers with casino interests. (White is allegedly "not Newsweek". We caught up with him in Berlin, though.) It was he who suggested buying the Ultimate Fighting Championship after its difficulties with McCain drove it to the brink of bankruptcy.

The brothers, Lorenzo and Frank Fertitta, were receptive. They had grown up in Las Vegas, the world's fight capital. If they'd lived in LA their father would have taken them to team games – to the Dodgers, say. Las Vegas had no team and Fertitta senior took his sons to fights.

As an adult, Lorenzo thought about boxing as a business. He couldn't think of any industry that generated billions in cash but had no brand associated with it. Boxing's brands were people such as Ali or Floyd Mayweather, today's world champion, and this made boxing vulnerable. When its stars ceased to shine, interest waned in the sport. Everything was built around one-off events.

Mixed martial arts offered a chance to do it differently. But it was in deep trouble. "UFC was a broken brand," Lorenzo told a business breakfast in London this year. "It had very bad connotations associated with it because when it started, there was essentially no rules." The price for the troubled league was $2m in 2001. Lorenzo (net worth today: $1.3bn) likes to say that all they got for the money was three letters – UFC.

The Fertittas were quick to see what others, such as the Murdoch family, would also conclude. Sport unlocks people's willingness to pay for media. Therefore media companies could be induced to pay for sport. And unlike boxing with its single events, UFC could be given size: a championship could sell a planned calendar of fixtures to TV companies. It's the business concept of basketball or football, applied to a full-contact fight sport. It didn't work. The Fertittas sank $40m into UFC with little effect. Lorenzo made a call to White suggesting it was time to get out.

Then everything changed.

In 2005, after approaches to every television network in the US had ended in failure, one responded. Spike TV liked the concept of a reality TV show – a sort of testosterone-fuelled Big Brother in which athletes live together and fight until a winner emerges. Spike was unwilling to pay for the series, so the Fertittas committed another $10m. "It turned out to be the best thing we ever did," said Lorenzo Fertitta, "because, since we paid for it, we owned it. We retained all the rights."

It was an immediate success – the biggest show on the network. And it helped UFC officials identify athletes with pull at the box office, who could then be signed and marketed for fights.

The Fertittas had stumbled on a winning formula. Compared with boxing, which was being produced in sober fashion for the American channel HBO, their sport was irreverent. Pumping music is part of every event. Soon they were generating the world's largest pay-per-view audience. And most UFC fans are under 30, an entire generation younger than in some sports (the average age of the TV audience for the Sochi Olympics was 55). When looked at as a business, UFC is not really a fight promoter; it's a media company.

OUTSIDE THE CAGE

This summer Joanne Calderwood, a former care home assistant from Scotland, entered a house in Las Vegas as one of 16 women competing to be UFC's first women's straw-weight champion in the reality show's 20th series. "I didn't know how frustrated I was until I started hitting pads and feeling much better, calmer, happier," whispers the soft-spoken Calderwood, recalling how her normal, suburban childhood was transformed when she went to a Thai boxing class, aged 13, to keep her younger brother company.

Two years ago she left Ashley "Smashley" Cummins, a St Louis County police officer, writhing with a broken eye socket after a sharp right knee to the face. "I am most myself when I am fighting. Outside the cage, it's not really me."

The job of growing UFC in Europe falls to Garry Cook, the former CEO of Manchester City FC. "The spectacle is the bit that upsets us," he says, effectively defining his job as selling violence to people who don't like it. "It's not pleasing to us. It's freakshowish. We're not asking people to go and be [fighters]. We're asking them to understand what it takes." He has been here before. Cook reached professional maturity at Nike, when the maker of trainers had a 48% share of the American market and wanted to go global. He gave a basketball player shoes that matched his car. Glorified him.

"Michael Jordan was the catalyst for the growth of Nike," says Cook. "Michael would argue if it wasn't for him there wouldn't be a Nike. Nike would argue if it wasn't for Nike there wouldn't be a Michael Jordan. It's an argument that's debatable for ever." His plan for UFC is to create heroes. Holding more fights in Europe will change nothing, he says: growth comes from the human appetite for stories. "Every sport should have three or four heroes on a global level," he says, "six, eight, 10 on a regional level. And then you've got all your local stories."

When he took the job in 2012, Cook knew that fighters have potential. On a tour with Manchester City two years earlier, he had faced the usual problem of how to entertain the team. Football players sit in their rooms with headphones or an Xbox. They are not known for an interest in museums.

One player, Craig Bellamy, asked to see some UFC fighters at a local gym. To Cook's surprise, instead of the usual empty team coach the club needed extra transport. He thought: "Something's happening here. People's sporting heroes have sporting heroes." His raw material has promise. Take Muñoz, one of the headline names in Berlin. As with Calderwood, his soft voice comes as a surprise. "You know, we're not unintellectual people," he says. "We know what it takes to be fierce inside the cage but gentle outside it. Gentleness is strength under control." His gift for martial arts, he says, has enabled him to save lives.

Save lives? Muñoz, 36, started training after he was bullied. They took his Jordan shoes – the very shoes Cook had helped make so desirable. He faked illness not to go to school. Then a friend led him to mixed martial arts. At his gym in Orange County, California, Muñoz now takes gang kids and teaches them. "I don't just teach them how to punch, kick, elbow, knee. I treat them with dignity and ask, 'How does it feel when I treat you this way? Does it empower you?'"

"With great power comes great responsibility. When I give somebody this power, they've got to be responsible. I say, you have to be gentle outside the gym." He says his alumni have jobs and families, and volunteer to do community work to keep themselves grounded. Muñoz, meanwhile, is harangued by his coach for directing too much energy to other people. In Berlin he lost his fight and was a picture of dejection.

Britain has Luke Barnatt, a personable fighter given to three-piece suits and stories. In the very first round of his first amateur fight he broke his jaw. He opened his mouth to show his coach, Robbie Oliver. "Just cracked a few teeth," said the coach. "Get back out there." Barnatt won the fight. "Well done mate," said Oliver, acknowledging the injury he had earlier denied. "Your jaw's broken. Better go to hospital."

Ireland has Conor McGregor, who dreamed of being a fighter as a boy and now has his chance to fight his way out of unemployment. Sweden has Niklas Backstrom, in tears in Berlin when he realised that victory meant he could now pay the rent. "The catalyst for growth for the next five years for UFC will be this elevation of athletes and their stories," says Cook. Also planned for Europe is a gym business.

CONFORMIST GENERATION

At Urban Kings, a gym near Kings Cross in central London, Newsweek found a lawyer and a fashion designer among those training in mixed martial arts. "It's really weird," says Hiren Laxman, who works in online advertising and is not the type to pick a fight, "because I think the stereotype of MMA is a lout. Most guys who train are really friendly. You break so many physical barriers you get to know people very quickly."

"Deep down, everybody has a different reason [for training]," says Josh Palmer, an instructor.

"For some people it comes down to vanity. For others, pushing themselves physically or mentally. Some have been bullied and want to feel a little more secure. Some people just want to fight." The last, he adds, "want to fight where they're not doing it illegally outside a bar".

What does the rise of MMA say about us? According to Taylor, the Liverpool academic, its popularity is part of a trend. Some research indicates that school students are choosing individual sports over team games.

"We come from a conforming generation," says Cook. "A team generation. You know, programmed television, four channels!" The growth in sport is in individual pursuits such as snowboarding and BMX. "It's about individual expression. I think MMA is part of that generational movement."

"Look, at the end of the day we're selling emotion," says Lorenzo Fertitta. We're selling adrenaline. And that's why we're connecting to that younger generation."

In May, Cook met a TV network from Greece. "I said I'd love to have an event in Athens, the home of the founding father of combat," Cook recalls. "Or in front of the Colosseum in Rome. And the world will say: wow, look at that. We've gone through two thousand years and we're back where we started."