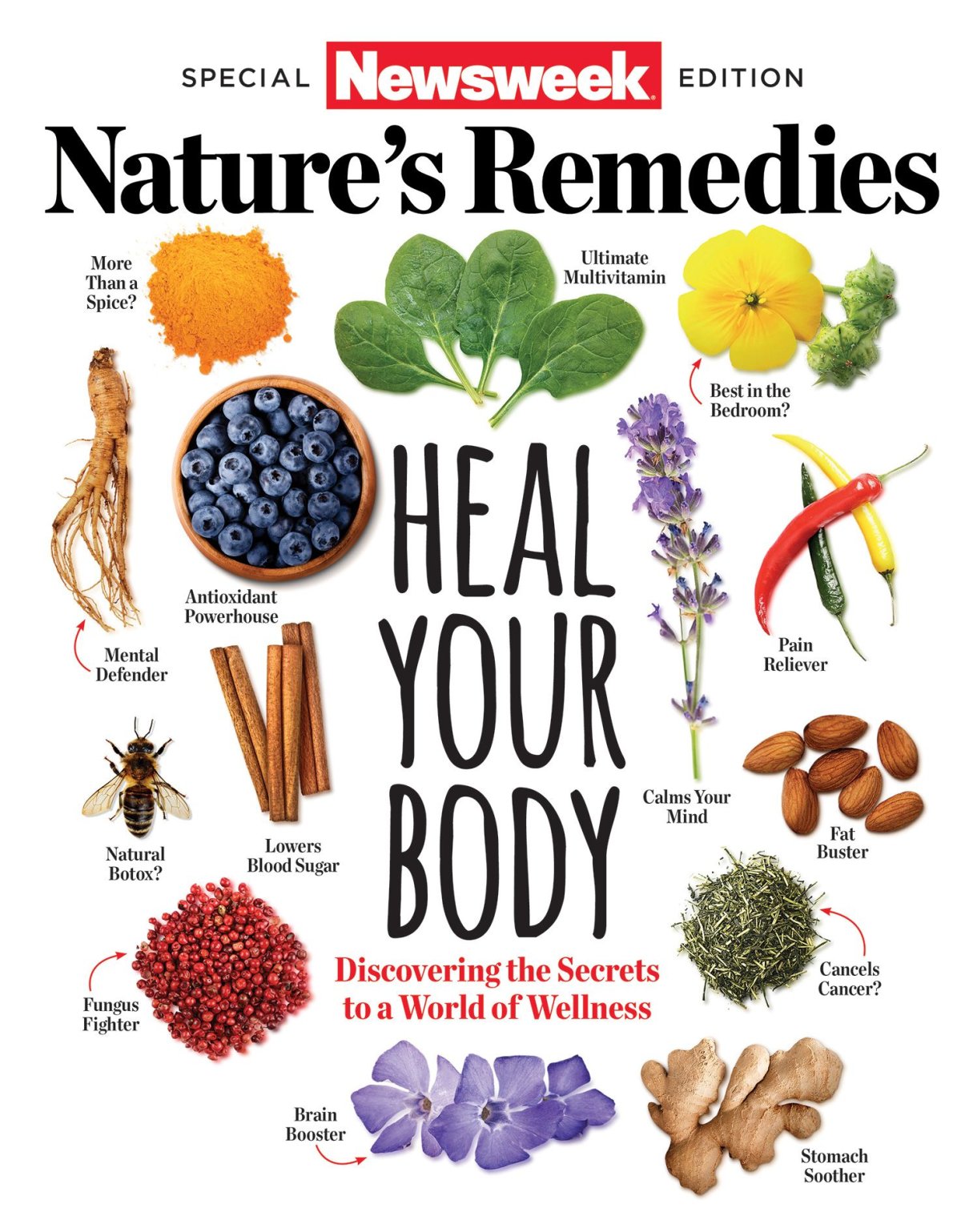

This article is featured in Newsweek's Special Edition: Nature's Remedies—Heal Your Body.

For thousands of years, standard medical procedures did more harm than good. Despite the best of intentions, untold millions of patients suffering from illness and injury met their end at the hands of those promising to heal, whether it was the barber-surgeon performing a bloodletting in 13th-century London or the priest of Apollo giving a sick person nothing more than a charm in ancient Greece.

Through the millennia, as the medical community's knowledge of the human body's inner workings has grown, so too has its ability to fulfill its mission of saving lives—particularly in the last century, which saw the advent of antibiotics, vaccines and other scientific tools that have doubled the global average expectancy from around 40 years in 1900 to an estimated 70 years today. But history, medical or otherwise, doesn't progress in a straight line. It moves in fits and starts, leaps forward and, occasionally, staggers back.

Humans may be living longer than ever, but some are questioning whether the infrastructure put in place to treat disease is having an overall positive effect on quality of life. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that in 2012, nearly half of the adult population in the United States (117 million people) suffered from a chronic illness or condition, and while many of those health problems can be traced back to the familiar culprits of obesity and heart disease, some medical professionals believe the current system is too quick to assign people a chronic disease. "I'm a conventionally trained physician, and I believe Western medicine can do a lot of good for people, particularly those who are acutely ill or injured," says Dr. H. Gilbert Welch, physician and professor at the Dartmouth Institute and author of Less Medicine More Health. "But at the same time, we can get into a sort of overkill situation where we do way too many tests and treatments that people can't benefit from because ultimately they're not destined to develop the problem at hand." In other words, despite having the advantage of the best medical training in human history, today's practitioners may be forgetting their trade's most basic tenant—primum non nocere ("First, do no harm").

It's not hard to realize where the zeal for early screenings for diseases comes from, particularly when it comes to the variety of cancers that have caused so much misery. In America, it wasn't until the 1960s that cancer screenings became a routine part of medical care, meaning thousands didn't discover they harbored cancers of the lung, breast, prostate or more until it was too late for treatment to save their lives. As technology improved to allow the early detection of more and more cancers (using inventions such as the mammogram and the fecal occult blood test, for instance), it seemed common sense to encourage as many people as possible to get checked for a potentially fatal disease. What could be the harm in just making sure?

According to Welch and others sharing his opinion, quite a bit. "Anticipatory medicine comes with some downsides," Welch says. "When we act and intervene for things that might happen in the future, the harm of our interventions occur now, and we can prematurely—or worse, unnecessarily—turn people into patients."

The debate in the medical community centers on the concept of "overdiagnosis." The classic example is a person who goes in for a prostate cancer screening that reveals an abnormality, which deems the person as suffering from the "disease," according to current medical practices. The problem is that the tiny tumor or abnormality may never develop into what we think of as full-blown cancer that impacts the patient's life.

This phenomenon has played-out on a national scale in South Korea. Around the turn of this century, the nation wholeheartedly embraced a massive screening program for thyroid cancer, which in turn revealed more and more people with cancerous tumors. The aggressive treatment saw thousands of South Koreans opt to have their thyroid glands removed, a procedure condemning each of them to a lifetime dependency on replacement hormone therapy. The result of South Korea's screening program can't help but give even the most ardent supporters of early detection pause—despite diagnosing 15 more cases of thyroid cancer in 2011 than in 1993, the death rate of the cancer has remained flat over the years, which experts worldwide agree means many of these new cases would never have threatened the lives of the patients who underwent unnecessary surgeries.

For many medical professionals in the United States, the situation in South Korea is a frightening harbinger of what could happen here. "It's a warning to us in the U.S. that we need to be very careful in our advocacy of screening," Dr. Otis W. Brawley, chief medical officer at the American Cancer Society, told The New York Times. "We need to be very specific about where we have good data that saves lives." While almost nobody is advocating abolishing screening altogether, professionals such as Welch believe casting as wide a net as possible does more harm than good, and instead efforts should be focused on ferreting out diseases in the populations proven more prone to them. "Screening can make sense when it's done in a group of people who are generally high risk [for that disease]," Welch says. There's a reason we don't have 18-year-olds lining up for colonoscopies. But as medical tools become more advanced and can more easily shine a light on the messy mysteries inside of us, it's hard to resist the urge to use them, even if they don't reveal anything we can—or should—act on. Doing nothing rarely seems an appealing option, even when it's the best course.

One specific way our "do something" medical culture has wreaked havoc is in the arena of antibiotics. It can (and has) been argued the widespread use of drugs such as penicillin have done more to change how we live than any of our greatest gadgets and inventions. Illnesses that once would have plunged patients into a life-or-death struggle can now be dismissed with a trip to the doctor and the local pharmacy.

The problem, which has been building to a head for decades, involves the pressure both patient and doctor feel to reach for these miraculous cures at the sign of every sniffle. "You have a sense that a person is sick, often with an upper respiratory infection or cold, and doctors know there isn't much purpose to using antibiotics for that, but they feel they need to recognize this patient is ill," Welch says. So the doctor gives out medicine he or she knows is not really needed, and when the patient recovers it's usually credited to the antibiotics, even though that's rarely true. "The idea that the human body has the ability to get well on its own gets lost in a very highly medicalized society," Welch says.

This overuse has given rise to new strains of disease resistant to antibiotics, and the world now confronts the terrifying prospect of a return to the days where every scrape and cut carried with it the risk of death. When a strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae claimed the life of a Nevada woman in January, despite its early identification and undergoing a barrage of 26 different types of antibiotic drugs, many wondered if the age of the antibiotic had already come to a close. Last September, the General Assembly of the United Nations gave credence to those fears when it declared the spread of antibiotic-resistant disease our "greatest and most urgent global risk." A global pandemic of a disease resistant to antibiotics could rack up a body count in the tens of millions—a grim toll that would put to shame even the most inept medical professionals found far in the past.

This article was excerpted from Newsweek's Special Edition: Nature's Remedies—Heal Your Body. For more on the definitive guide to alternative methods of healing the mind, body and soul, pick up a copy today.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.