The first wave of emotions, victims say, is a combination of panic and powerlessness. They click and reclick on files on their desktops—agendas for the weekend Christian camp, payroll data for hundreds of teachers or medical information for veterans—to no avail. Someone, or something, has converted the files to foreign MP3 files or an encrypted RSA format. And next to these unopenable files the victims get a ransom note in a text file or HTML file: "Help_Decrypt_Your_Files."

"All your files are protected by a strong encryption with RSA-4096 [military-grade encryption]," reads one note shared with Newsweek by a victim. "So, there are two ways you can choose: wait for a miracle and get your price doubled, or start obtaining BITCOIN NOW!, and restore your data the easy way. If you have really valuable data, you better not waste your time."

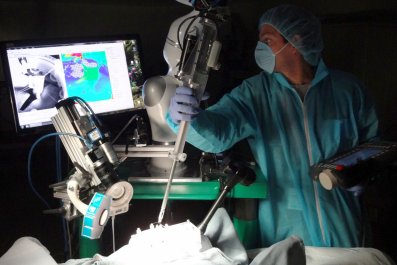

In February, Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center in Los Angeles made national news after it was the victim of ransomware, a virus that blocks owners from accessing their files. For weeks, the hospital had to shuttle its patients to nearby facilities. But hackers aren't going after only big targets. In the past few months, school districts in South Carolina and Minnesota, hospitals in Kentucky and Georgia, and a church in Oregon were paralyzed for days, and many experts believe there are far more ransomware attacks that have gone unreported.

Institutions have resorted to using handwritten forms as they try to retrieve data that is locked by military-grade encryption. In many cases, the victims cough up hundreds or thousands of dollars in untraceable, open-source cryptocurrency for the key that will allow them access to their own information.

'World War III'

Some cybersecurity experts call the attacks an epidemic. Both the United States and Canadian governments issued a rare joint alert in March warning businesses of ransomware. In 2015, affected Americans paid about $325 million due to ransomware attacks; in 2016, cybersecurity analysts estimate, it will be much higher.

"Ransomware is dangerous because anyone can [use] it and target anyone," says James Scott, a senior fellow at the Institute of Critical Infrastructure Technology.

"There are two types of organizations now: those who have been breached and those who have been breached but [don't] know it yet. 2016 will be the year of…ransomware."

While the culprits come from all over the world, ransomware attacks are mainly coordinated by highly organized mercenary hackers based in Russia and other Eastern European countries, prompting some to hark back to Cold War–era concerns. "This is World War III," says Clint Crigger, a cybersecurity manager for SVA Consulting, though he insists he is not an alarmist.

Firewalls or antivirus programs do a terrible job detecting ransomware, but those are not the cause of the epidemic. It lies, instead, with the people's carelessness in clicking on phishing emails and infected advertisements, multiple experts say. Two-thirds of ransomware cases stem from phishing emails, according to cybersecurity research company Lavasoft.

Rookie hackers, known as script kiddies, can easily scrape together a fake email from a senior hospital doctor or school superintendent laced with ransomware viruses using social engineering. A common method is mass-collecting email addresses from the company's domain name, identifying the top executives of the company using LinkedIn or Facebook, creating a fake email address under one of those executives' names and sending a ransomware-laced email to a lower-level employee with a subject line reading "Invoice" or something else that looks as if it demands attention.

Another variant is sending a phishing email under the name of your mailman. One ransomware attack at a Georgia Veterans Affairs hospital began with an employee clicking on a fake USPS email, paralyzing the hospital for three days.

David Eppelsheimer, the pastor of the Community of Christ Church in Hillsboro, Oregon, can speak from experience. He found all his PowerPoint files mysteriously converted to the MP3 format on February 18, and he got a curt ransom note asking for 1.3 bitcoins—about $500 to $800. "I felt helpless, and it felt surreal," he tells Newsweek.

After two days of frantically trying to obtain bitcoins in shady-looking online markets, Eppelsheimer paid the hackers $570 of his own to obtain the encryption key to open the files. He said it took several weeks to retrieve and open hundreds of his personal files, one by one.

Several cybersecurity experts tell Newsweek that paying ransom should be considered only in the worst-case scenarios, when one has no backups or lines of defense in place—much like Eppelsheimer. Paying ransom allows the hackers to carry on their ransomware activities. "If you pay the ransom, what you are saying is, you have been caught with your pants around your ankles," Crigger says.

Charles Hucks feels like he had no choice. As the executive director of technology at the Horry County School District in South Carolina, he became a victim of ransomware. For a few weeks starting on February 8, his county's networks were frozen, bringing the daily routines of 42,000 students and thousands more staff and teachers to a halt. Despite having ready backups and a full-time information technology staff working 20 hours daily to get the data back, Hucks and the school district still had to pay 22 bitcoins ($8,500) to the hackers for the key as a "business decision."

Defenses Against Ransomware

But experts say institutions and people aren't helpless against ransomware. The best thing to do is to back up data frequently, on a cloud storage platform, with cold storage or on an external hard drive. Scott also advocates training employees about "cyberhygiene," comparing not clicking on malvertisements to washing one's hands before working in a restaurant or hospital. "Loose clicks sinks ships," Crigger says.

If a company or server is breached, the recommended procedure is to cut off all servers from public access to prevent the virus from spreading and then having IT professionals comb every folder and network for infections. Scott says institutions need to be vigilant about ransomware viruses acting as diversions as they launch an attack elsewhere in the network, perhaps downloading a company's personal data to sell on the black market. One way to detect it, Scott says, is to monitor for abnormal spikes in downloads and other activities in unaffected networks during attacks.

But even some cybersecurity experts seem to have a fatalistic view. Ransomware viruses are constantly evolving, with some able to self-mutate around anti-virus programs and security controls.

Without a massive overhaul in cybersecurity infrastructure and an understanding of cyberhygiene, keystone institutions like small hospitals will remain easy targets. But Scott worries that even more critical and outdated systems that control dams or nuclear silos built during the Cold War with minimal upgrades can be similarly hacked.

The scale of the danger hit Scott during a recent visit to a small town in Virginia's Shenandoah Valley, where people seemed oblivious of such dangers. "I was thinking, I can go to a public computer right now and take down a local hospital in a day," he says.

For victims like Eppelsheimer, it can be hard to deal with a faceless attack that can seem very personal. "My theology is…love my neighbor even if he steals from me," Eppelsheimer says. "But I was angry at the moment. It felt like a faceless, nameless evil from the other side of the world descended on me and my church."