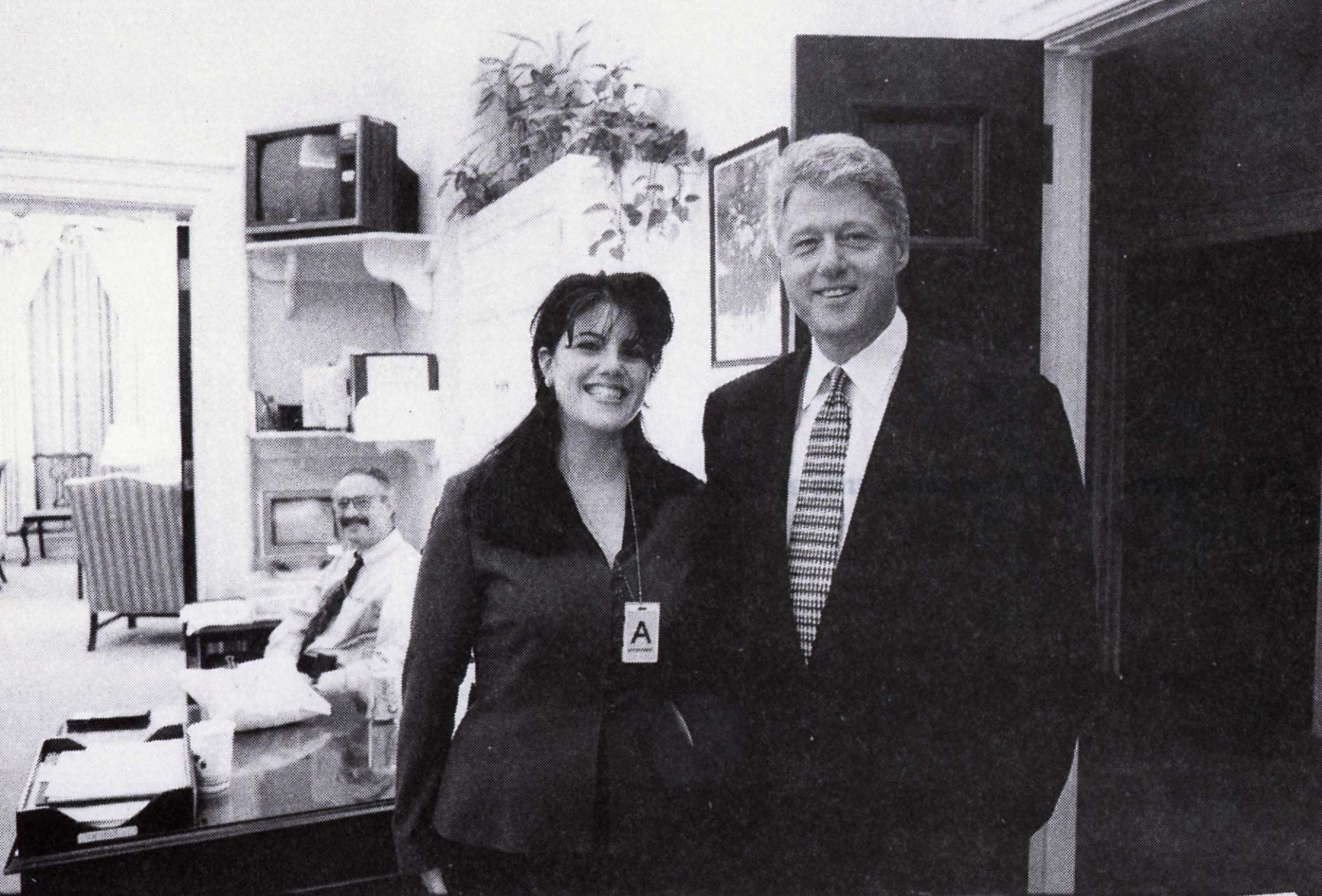

Newsweek published this story under the headline "Monica on the Stand" on August 17, 1998. In light of recent news involving President Donald Trump and his potential impeachment, Newsweek is republishing the story.

David Kendall didn't waste time. When the news broke late last month that Monica Lewinsky had finally struck an immunity deal with Kenneth Starr, the president's lawyer began working the phones. He'd received an intriguing fax from a man named David Bliss, who said he had a story about Lewinsky that Kendall might want to hear. Kendall quickly faxed him back, thanking Bliss for sending the "very welcome" material "out of the blue." Kendall followed up with a phone call to Bliss, leaving a solicitous message—which Bliss played for Newsweek—on his answering machine. "I think it's important that we get together and, you know, decide how to proceed," Kendall said. What did Bliss have on Lewinsky that was so tantalizing to the president's lawyer? Bliss, a drama-department shop foreman at Lewis & Clark College, told Kendall that when Lewinsky was a 21-year-old student there in 1995, she had forged a letter in his name on school stationery. Apparently Lewinsky was trying to help out Andy Bleiler, a married drama coach with whom she was allegedly having an affair. Bleiler was out of work, and embroiled in a custody battle. The forged letter—a purported job offer from Bliss to Bleiler—was supposed to help Bleiler's case. But the scheme went bad when the letter—which Bleiler says he never knew about—was returned to Bliss's mailbox as undeliverable. Bliss immediately suspected Lewinsky, who had been pestering him relentlessly to find work for Bleiler. Confronted with the letter, she proclaimed herself "humiliated," and begged forgiveness. But Bliss wasn't the forgiving kind. He took his story to Kendall. (A lawyer for Lewinsky declined to comment.)

The president's lawyer was all ears. Now that Lewinsky has become a fully immunized witness for the prosecution, Kendall is looking for details that might enable him to undermine Monica's credibility. Last week Lewinsky spent six hours before the grand jury in Washington. There, under oath, she apparently contradicted the president's denials —both in his Paula Jones deposition and to the country—that the two had a sexual affair. The basics of Lewinsky's testimony began leaking to the press soon after she left the courthouse. The former intern reportedly admitted to more than a dozen sexual encounters with the president—and said that she and Clinton discussed how to conceal their relationship. But on the question of whether Clinton explicitly asked her to lie under oath, Lewinsky refused to testify that the president instructed her to perjure herself.

As Kendall prepares his legal counteroffensive—and with Clinton's August 17 testimony just a week away—there are obstacles everywhere. Any lawyer's biggest fear is a surprise question that leaves his client befuddled and in danger of falling into a perjury trap. This is exactly what Kendall is up against. The biggest unknown, and one that could conceivably wreck all of Kendall's careful preparation, is the blue dress currently undergoing testing at the FBI lab. Does it contain "DNA evidence"? The crime lab may have already completed initial tests. But the end results—and whether Starr will ask the president for a DNA sample—are being tightly held. If the tests come back positive, and the results are linked to Clinton, anything Kendall might have dug up to discredit Lewinsky might be rendered irrelevant. But Kendall doesn't have the luxury of knowing what those tests will reveal. The best he can do is prepare his case—and his client—and get ready for the worst.

Meanwhile, Starr's staff is moving rapidly to complete its probe and may submit a possible report to Congress by early September. Contrary to expectations that Starr would present evidence of a broad pattern of obstruction of justice, Newsweek has learned the report will focus only on the Lewinsky matter and other allegations flowing out of the Paula Jones case. After four years and more than $ 40 million, the independent counsel has won a string of Whitewater criminal convictions and still has two indictments pending. But whatever evidence Starr has developed against the president relating to Whitewater—and other matters such as the travel office affair and the FBI file scandal—sources say it is not strong enough to be included in an impeachment report. The findings could potentially cut both ways. The narrow scope of the report will allow White House spinners to denigrate Starr's entire probe as little more than a sexual inquisition. But a tightly focused report could present problems for the White House—laying out the lurid Lewinsky charges in stark and simple language that may be difficult to dispute.

No matter what Starr's report reveals, Kendall's immediate problem remains the same: how to make Clinton appear more credible than Lewinsky. One option: do "oppo" research on the chief accuser. Before Lewinsky reached an agreement with Starr, Kendall tread lightly on her past to avoid pushing her into the independent counsel's camp. Since she's cut her deal, however, Kendall is no longer restrained. For now, the lawyer is keeping potentially damaging stories in his briefcase. But they could prove useful to him during possible impeachment hearings, when Democrats loyal to the president would get the chance to interrogate the former intern.

Kendall's Lewinsky digging isn't confined to Monica's Lewis & Clark days. He is also interested in the story of a Democratic activist from Indianapolis named John Sullivan, who recalled meeting Lewinsky at an October 1996 fundraiser in Washington. As he waited along the rope line to shake Clinton's hand, Sullivan says he was pulled aside by an event organizer. She told him that the woman standing next to him was named Monica and that Monica was infatuated with the president and may have fantasized about having a relationship with him. Would Sullivan keep an eye on her? The incident came to light last week when an Indianapolis TV reporter saw a tape of the event and recognized Sullivan—who then told his story to the reporter. Sullivan told Newsweek Kendall called him last week and asked about the event. Sullivan says the smooth lawyer, himself an Indiana native, played up his Hoosier roots to try to win Sullivan's trust.

Soft-spoken and camera averse, Kendall has a reputation as a gentleman lawyer. But he is a tenacious and crafty litigator with a reputation for tying his opponents in knots. Starr has already gotten a taste of Kendall's tactics. When the president's lawyer petitioned the courts to investigate the independent counsel's alleged grand-jury leaks to the press, it was seen as a somewhat desperate publicity stunt. But last week it was revealed that Judge Norma Holloway Johnson came down on Kendall's side—ruling that there probably were illegal leaks, and ordering Starr to prove his office wasn't the source. Last week a federal appeals court handed Starr one minor victory on the matter: It denied Kendall the opportunity to interrogate Starr's prosecutors about the leaks. Still, Johnson's decision was a blow to the independent counsel, and gives new ammunition to the White House spin team that Starr is out of control.

In public, the president is trying to rise above the legal imbroglio. After the embassy bombings in Africa last Friday, Clinton solemnly vowed to bring the terrorists to justice. This week, as the flag-draped coffins arrive home, the president will have other opportunities to emphasize statecraft over scandal. But those who saw Clinton last week after hours described him as burdened and withdrawn, rubbing his eyes and staring absently into space.

It's up to Kendall to take his dispirited client and transform him into a compelling, telegenic and credible witness. He's done it before. When Clinton gave videotaped testimony in previous Whitewater trials, jurors said they were "beguiled" by the president's performance. But trying to explain an alleged affair is a taller order. Kendall is legendary for exhaustive preparation sessions in which he grills his clients over and over, day after day, making them repeat their answers. In a case this complex, with so many possible hidden traps, that means the president and his lawyer will be spending plenty of quality time—and billable hours—together this week. The drill has already begun. In the mornings—and sometimes again in the evening—Kendall and his partner Nicole Seligman slip into the White House. They use the East Entrance to the private quarters, avoiding the cameras along the West Wing driveway. There, in Clinton's second-floor office overlooking the South Lawn, Kendall methodically runs through the evidence, asking the president to explain everything from Lewinsky's White House visits to her high-powered job search. There are usually only two others allowed in the room: Hillary Clinton and Mickey Kantor, another private lawyer.

No matter how thoroughly Kendall preps his client, however, he can't anticipate every question the special prosecutor might ask. Even Starr doesn't have all the answers. For months, for example, there have been numerous hazy press reports that a uniformed Secret Service officer witnessed an alleged encounter between Clinton and Lewinsky. The story has changed over time, and the details remained sketchy.

A Newsweek reconstruction of the events may shed some light on the incident. On Easter Sunday 1996, according to government lawyers, officer John Muskett was stationed outside the Oval Office. A phone call came in for the president, but Clinton didn't respond. Muskett couldn't locate the president. Spotting Harold Ickes, Muskett asked the then deputy chief of staff for help. They knocked on the door to the Oval Office, but got no response. They then went to the door of the president's nearby private study. They knocked again, then opened the door.

What happened next is a matter of some controversy. Muskett later told Secret Service and Justice Department lawyers that he merely saw Lewinsky emerge from the room Clinton was in. But a fellow Secret Service officer, Gary Byrne—who wasn't present that day—told the government lawyers a different version. He said Muskett had told him that when they opened the door, Lewinsky's head was in Clinton's lap. Muskett has denied Byrne's account. And Ickes says he doesn't recall any aspect of the story. But sources tell Newsweek it was likely this incident that prompted Byrne to warn senior Clinton aide Evelyn Lieberman that Lewinsky was hanging around the Oval Office and might be a potential problem. Shortly afterward, Lewinsky was transferred out of the White House to a job at the Pentagon. Now, Newsweek has learned, Starr's prosecutors, confronted with the contradictory accounts, want Justice Department officials to tell them what they were told in their interviews with Muskett and Byrne. Justice might agree to do so as early as this week. (Neither Muskett nor Byrne would comment to Newsweek.)

With a week to go, Clinton aides are doing their best to conduct business as usual. This week Clinton will crisscross the country raising money for congressional Democrats and presiding over official White House "message events" wherever Air Force One touches down—touting voter favorites like the patient's bill of rights, clean-water laws and gun control.

But Clinton's mind may be elsewhere. Last week the president and First Lady invited a group of youth-violence experts to a cozy dinner in the Blue Room of the White House. There they hashed over the latest social theories about juvenile-crime prevention. According to some guests, Clinton, who normally revels in after-hours wonk sessions, seemed at times detached and wary. He faded in and out of the conversation and was difficult to engage. Mrs. Clinton carried the dinner for both of them. She eagerly took notes and peppered the assembled academics and religious leaders with detailed questions. At the end of the evening, after most of the guests had departed and the First Lady had gone upstairs, Clinton lingered with Harvard professor Cornel West and a few others. How can you maintain your faith in the system when "right-wing gangsters in ties" seem intent on tearing you down? West asked the president. "They've been at me for a long time," Clinton responded. "I'm prepared." David Kendall certainly hopes so.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.