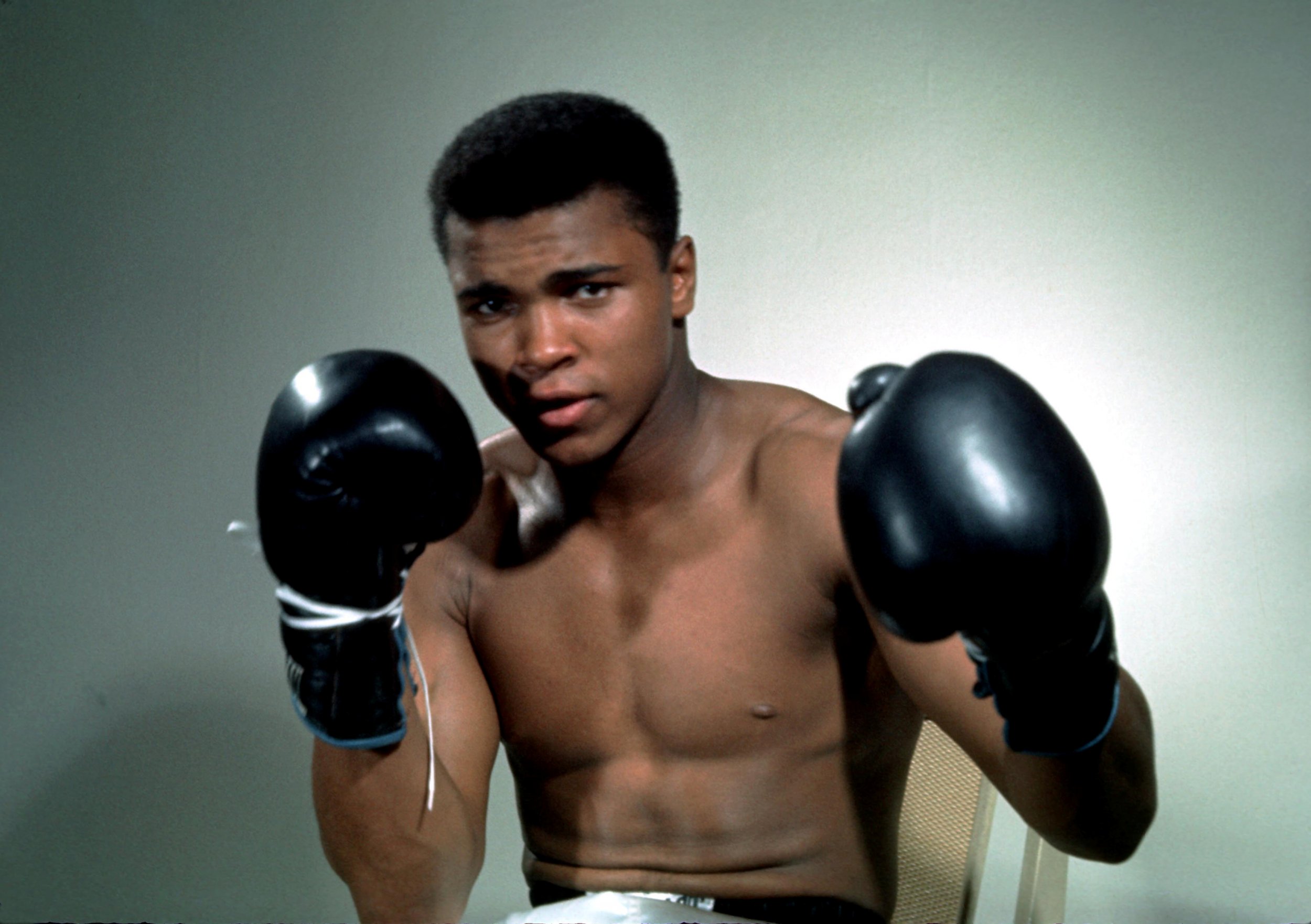

Muhammad Ali has died at the age of 74. Newsweek profiled the beloved boxer in 1964, on the occasion of his historic heavyweight championship upset. "My name is magic," declared the 22-year-old athlete, who was still going by his given name, Cassius Marcellus Clay. This story originally appeared in the March 9, 1964 issue of our magazine, with the headline "And I'm Already the Greatest!"

They carried the corned beef out of the ballroom. They cased up the gin, wheeled away the canopied bar, and turned out the lights. Sonny Liston's victory party at the grand and gaudy Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach was over before it began.

Incredibly, the man believed to be the most powerful athelte of his time had given up the sports world's most valuable title while sitting, quietly glowering and in full possession of his senses, on the ring stool. Outlandishly, 22-year-old Cassius Marcellus Clay had become world heavyweight champion.

And it seemed wrong—on so many counts. Some doubted that Liston, who had been throwing lefts all night, had injured his left upper arm badly enough to quit. Others—and they weren't all plump sportswriters—recalled doughtier champions: John L. Sullivan spitting out teeth and then wading into Jake Kilrain; Sugar Ray Robinson fighting himself into heat prostration against Joey Maxim; broken-knuckled Gene Fullmer battling on against Florentino Fernandez. Still others simply could not believe in any upset by an 8-to-1 underdog, even given the reputation of the fight game and Liston's own criminal record and underworld associations.

Menace:

Finally, the fight seemed wrong because the new champion was so anticlimactic. Liston had been the epitome of power and menace. With a glower, a thick-armed gesture, he transfixed before he punished. But Cassius Clay was immaturity itself, a brash, over-handsome movie actor of a fighter.

At times he was hysterical. "I'm the greatest—the prettiest that ever was!" he had screamed at the weigh-in, and the reporters had stared with something of the horror of the normal for the possessed. Sonny Liston, weighing 218 to Clay's 210 1/2 and watching with contempt, made a circular motion with his hand over his forehead. For his wild antics, Clay was fined $2,500 by the Miami Beach Boxing Commission. The commission doctor said the young challenger was "scared to death." So strikingly odd was his behavior that later reporters waited at his dressing-room door to see if he would actually emerge.

Smooth:

He did. He walked past the reporters as if he were any other fighter before a match, and later he went into the ring like any other fighter. And he went to work like no other fighter Liston has faced since Eddie Machen lasted 12 rounds with him almost four years ago. Before a half-empty auditorium (8,297 spectators; the promoters lost $400,000 on the house), and more than 600,000 watching via 371 Theater Network Television hookups (they paid more than $3.5 million), he moved smoothly and swiftly around the thick, lumbering Liston. Sonny threw punch after punch, trying for a quick knockout, wrenching his left upper arm at this time, so he said later. But Clay stayed away, his arms mockingly low, countering now and then, not running, but not trying to slug back either. ("If Patterson had done that, he'd still be champion," Cus D'Amato, the ex-champ's adviser, grumbled.)

Clay won the first round; Liston, the aggressor, took the second, but it was slow going, and Clay was still fighting his own fight. In the third Clay opened a cut under Liston's eye which later needed six stitches. In the fourth round Liston seemed to connect solidly, but Clay never wavered and now he was bruising other parts of Liston's face. "I never seen him cut before," said heavyweight Marty Marshall, who until last week was the only man to defeat Sonny.

Clay came back to his corner after Round 4, looking nimble and still unmarked, but he rolled his head suddenly in pain and clutched his eyes. "I can't see," he gasped to his trainer, Angelo Dundee. "Cut off my gloves. Call off the fight." Frantically Dundee worked over the eyes, trying to discover what had gotten into them. (He never did.) Finally he pushed the fighter to his feet. "This is the big one, Daddy," he said. "Let's not louse it up."

Now came Caly's finest moments. Nearly blind, he staved off Liston's heavy rushes, avoided blow after blow. Sensing a new weakness in his opponent, the old champion put on the pressure. But it wasn't enough. Again he could not stagger Clay; indeed, he looked amateurish in his attempts. Repeatedly Cassius snaked out a long left hand and seemed to rest it on Liston's bulbous nose as he kept the champion out of range. "I could have broken that arm for him," Liston said later.

Countdown:

Clay's vision cleared toward the end of the round and referee Barney Felix, who later said he had been about to award a TKO to Liston, changed his mind and let the fight continue. In Round 6 Clay was moving cleanly and swiftly again. The round ended and to most observers the fight was about even on points at this time. But Clay was fresh and vibrant, on his feet at the ten-second buzzer. Liston, still seated, looked old, with middle-age folds of neck flesh behind his head over the hugely muscled shoulders. And Liston still sat. Clay moved his lips, counting as is his habit after the warning buzzer, "1-2-3-4-5-6-7 . . ."

Suddenly he pranced about, raised his arms in victory, and gave a delighted whoop. "I'm the greatest," he yelled. "King . . . I'm king!"

He had seen Liston spit out his mouthpiece, had known before the crowd that the champion had quit.

Half an hour later he had a fast, unorganized press conference; indeed, it was more a press confrontation. "Who's the greatest?" he crowed at the bewildered writers who had overwhelmingly discounted his chances. "Who's the greatest?" A few answered half-heartedly. Unsatisfied, he kept haranguing them, kept asking the question. Finally a few more appeased him with a "Cassius Clay." Then, though no one had asked the question, he shouted: "You can't call it a fix. I didn't stop the fight."

Next day Cassius was a new man—or a new boy. He faced the reporters again and spoke slowly and with dignity. But if the message was lower keyed, it was as garbled as ever. In a single five-minute period he promised Liston a rematch, offered to fight anybody, "even two contenders at once," and then said he might retire because he didn't like fighting and hurting people. Unsmiling, he warmed to his favorite topic. "Everybody loves me now. My name is magic. I'm a wise man, not dumb. A dumb man couldn't think up a $7 million gate."

Muslim:

Later he was asked if he was a Black Muslim. "I believe in Islam," he said. "I'm not a Christian. But why's everybody so shook up when I say that? I don't wanta marry no white woman, don't wanta break down no school doors where I'm not wanted."

Liston came to his own press conference in black glasses, a blue arm sling, and a small cheek patch. Never had he seemed so relaxed, so approachable. As the fight wore on, he said, his left glove felt "like it was full of water." He belittled Clay, saying several men he'd beaten were better fighters. "Patterson came to win or lose," Liston said. "He didn't run or hide like he stole somethin'." Asked why he showed so little emotion over losing the title, Liston answered enigmatically, "We can only sing together. We can't talk together." Closing the conference, someone called out "Thank you, Mr. President," the way White House press conferences are closed. There followed a scattering of applause, and Liston looked surprised, then pleased and touched.

By now certain new details were coming out. Eight doctors had examined Liston and certified that the tendon of his left bicep had in truth been torn and divided, that he probably couldn't have properly defended himself. The boxing commission, which had threatened to impound Liston's purse, changed its mind. Soon after, the Internal Revenue Service filed liens against it for tax purposes. And when it came out that a day before the match Liston's company, Inter-continental Promotions, Inc., had paid $50,000 for the right to promote Clay's next fight if he won the championship and to name his opponent, Sen. Philip Hart, Michigan Democrat, threatened a Congressional investigation. Meanwhile, betting centers all over the country had been checked, and nowhere had the odds fluctuated as they normally do when a fix is in. (But rumors persisted New York odds on the fight had suddenly dropped to 4 1/2–1.)

In His Corner:

If Liston's claim is accepted that his upper arm was hurt early in the fight, his subsequent awkwardness and inability to hurt Clay were explained. Liston is primarily a left-hand puncher, but his power and timing were gone—he couldn't twist his arm properly as he landed—and he badly needed his left to fight a running opponent. The fact that he chose to lose in his corner rather than allow himself to be chopped to bits during nine more rounds proved only that, beneath the sullen animal gaze and under the frightening body, there is a sensible, civilized man. In defeat, Liston seemed as never before to have entered the human race.

To the press the fight was an unmitigated embarrassment. Columnist Jerry Izenberg of the Newhouse newspapers hurried a note to his sports desk. "Please burn, kill and otherwise destroy early column. It could have been worse. I could have picked the Japs in WW II." In a poll of sportswriters on hand, 46 had said Liston would win, and only three had voted for Caly. But even writers from other fields had jumped on the noisy youngster's back. Hearst columnist Frank Conniff predicted "a fistic travesty." Norman Mailer, covering for Esquire and sitting next to Gloria Guinness of Harper's Bazaar and Truman Capote, recalled the weigh-in and said, "He's close to dementia now." After the fight the Herald Tribune's Red Smith was ruefully eating his own prose: "The words don't taste so good, but they taste better than they read." And chirpy Arthur Daley of The New York Times was gamely searching for nice things to say about Clay, after columns of denigration.

Money:

And what of Cassius himself . . .? Ahead loomed Selective Service, and with his religious beliefs, Cassius might well claim to be a conscientious objector. Alternatively, there was the rematch possibility, with doctors saying Liston could begin training in three months. Ahead also was a very great deal of money, and the first glum Madison Avenue reaction ("He wouldn't be believable endorsing products") was fast reversing. Offers were pouring in. Three days after the fight a rhythm-and-blues record he had cut last fall suddenly took off; more than 100,000 requests for it were made in one day.

But Cassius Clay is young and his world lies ahead. In its own way the heavyweight championship, like the Presidency, is a great uplifter. It made a man of poise and affluence out of Rocky Marciano, a civic leader of Floyd Patterson, and it even seemed to humanize Sonny Liston. Cassius may grow, he may change. "Only 22 years old and I'm already the greatest!" he exulted in the first moments of victory. And he is a young 22, if not younger than springtime, at least as young as the youngest Beatle. There is no limit to his horizon.

This article originally appeared in the March 9, 1964 issue of Newsweek.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.