Paris—"In the Merah household, we were brought up with hating Jews, the hatred of everything that was not Muslim."

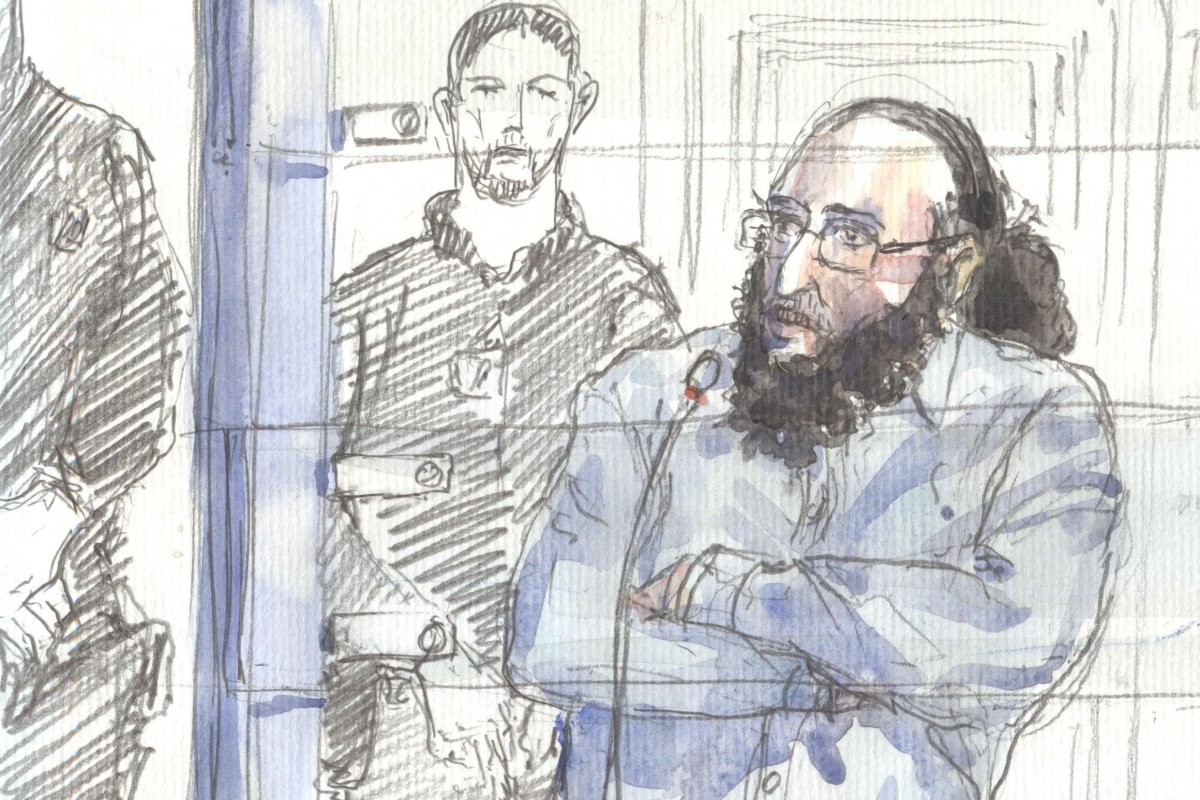

These were the chilling words of Abdelghani Merah at the trial of his brother, Abdelkader Merah, who was accused of conspiring with a third brother, Mohamed, to murder three soldiers, three Jewish schoolchildren, and a teacher in Toulouse, France, in 2012.

Abdelghani also revealed, at the time, that "when the medical examiner brought [his] brother's corpse home, people came over. They cried tears of joy. They said that he had brought France to its knees. That he did well. Their only regret was that he had not killed more Jewish children."

These appalling remarks, which suggest the environment in which Mohamed Merah was immersed and his family's way of thinking, have sparked a debate about the extent of hatred of Jews in the French Muslim community.

For years, it has been nearly impossible to speak about French Muslim anti-Semitism.

Many refused to take notice for reasons of ideology, discomfort, or lack of courage. Many feared being accused of "playing into the hands of the far right," and others thought it inconceivable that a French Muslim minority, itself victimized by discrimination and racism, could itself be guilty of racism and even violence. So for too long there was silence.

The Merah trial exposed a reality in France: anti-Semitic roots run deep within some elements of the French Muslim community. It is due to several factors, among them: manipulation of the Palestinian cause, failure of integration into French society, radical preachers and the funding of mosques, and satellite television stations broadcasting a steady stream of anti-Semitic discourse.

Whatever the reasons, the problem is spreading. And because France has waited too long to address the issue, Islamist extremists have cashed in. Adding to this already combustible mix is social media, through which anti-Semites broadcast anti-Zionism and conspiracy theories as a popular weapon against Jews.

A recent illustration of the impact of social media came in reaction to the Tariq Ramadan affair, in which the well-known Muslim scholar has been accused of raping and sexually harassing several women.

In the days after the revelations by Henda Ayari, the first alleged victim to accuse Mr. Ramadan, a huge wave of threats and insults were posted on French Muslim web sites and social networks calling her—among other epithets—a "whore paid by Zionist Jews to smear Tariq Ramadan's good name."

The phenomenon of French Muslim anti-Semitism was first noted only by a few academics and groups like the American Jewish Committee (AJC) as early as 2000, when anti-Semitism exploded in France in the wake of the second intifada. Anti-Semitic acts ramped up dramatically at the time, going from 81 incidents in 1998 to 744 in 2000.

There have been a number of studies tracing this disturbing trend, notably by Fondapol in partnership with AJC (in 2014 and 2016), showing that deeply-rooted anti-Semitic stereotypes continue to be widespread in certain Muslim communities in France.

While the number of anti-Semitic incidents in 2016, 808, remains similar to the 2000 figure, these are rarely related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict anymore. The problem now is structural.

It exists on the far right, the far left, and among Muslims with a fundamentalist vision of Islam, just as in several other Western European countries. Yet French anti-Semitism is distinguished in Europe by its level of violence, ranging from attacks to abductions and even to murders.

But only recently have a few intellectuals and politicians, in particular from the political left, dared to speak out. Notably, former Prime Minister Manuel Valls, a Socialist, was among the first to describe, denounce, and combat it, and also to criticize those on the left who opposed him, because he understood that the fight against anti-Semitism, from wherever it comes, was and is a fight for France's values.

Now, some French Muslim intellectuals are speaking out. The most recent example is film director Said Ben Said, who, writing in the French newspaper Le Monde , clearly and courageously criticized Arab Muslim anti-Semitism, after learning that he would not be allowed to sit on a film jury in Carthage because he had produced films in Israel.

The moral courage of such Muslim intellectuals should be commended because we know how difficult it is for them to make themselves heard. Journalists often prefer to invite more controversial figures such as Tariq Ramadan to their TV and radio shows.

And even when these intellectuals are invited, the simple act of denouncing anti-Semitism and extremism makes them susceptible to criticism, insults, and even threats of violence.

They are afraid. How could they not be, when they see that jihadists assassinate French Muslim soldiers and policemen because they are considered apostates, or that outspoken Muslims who denounce violence need police protection?

But their voices are more important than ever. Islamist extremists endeavor to separate Muslims from the rest of society by making them believe that France is an "islamophobic country" and that their "community" is not the French community, but only the " umma " (Arabic for "nation"). That makes Muslim denunciations of anti-Semitism and extremism all the more vital.

Also, since the far right plays on public fear by trying to convince French people that all Muslims are potential terrorists, moderate French Muslims are crucial in preserving the country's universalism and pluralism.

All of France needs to support these morally courageous voices. Only if the country as a whole confronts the reality of anti-Semitism can France continue to uphold its cherished values of human rights, "liberté, égalité, fraternité."

Simone Rodan-Benzaquen is Director of the American Jewish Committee Europe.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.