John Matthews had long been a shadowy presence in his son Dan's life. Every six months it was a new city, a new state, a new apartment. Dan, who lived with his mother, suspected something illegal was going on. He was estranged from his father and even used his stepfather's last name, Candland. Once, when Dan was 16, Matthews called him from a pay phone to say he was going underground and might appear on the television show America's Most Wanted. Months later, when they reconnected, neither brought it up.

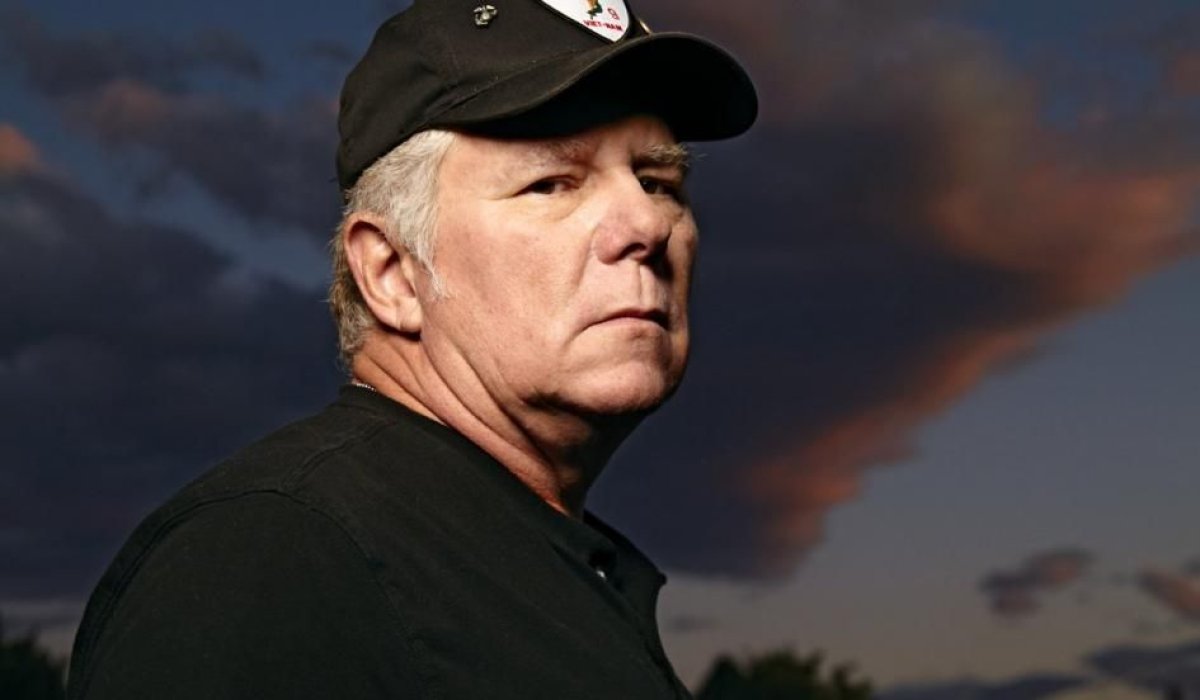

Matthews, who is now 59, recognized how he must have looked to his son: a troubled Vietnam veteran, a paranoid man who wandered between jobs and marriages, despised the government, and always kept a camouflage backpack filled with food, water, and clothing by his bedroom door. "Danny always figured I was trash," Matthews says. "Or a bad person."

Now they were outside the federal courthouse in downtown Salt Lake City; Dan, 33, had no idea why. A grizzled man in a Stetson hat smoking a Toscanelli cigar introduced himself as Jesse Trentadue, attorney at law, and led them into his office across the street. There, Matthews divulged the secret he had harbored for two decades: while his family thought he was hiding from the law, palling around with white supremacists and other antigovernment activists, he was working as an informant for the FBI, posing as an extremist to infiltrate more than 20 groups in an effort to thwart terrorist attacks. "[Dan's] eyes got bigger and bigger," the lawyer recalls. For Dan, the revelation brought sanity to a childhood of mystery and frustration. Finally, he says, "it all made sense."

It is rare for an informant to unmask himself, especially one who has found his way into the violent world of heavily armed bigots. But Matthews had developed a fatal lung condition and a drastically weakened heart, and he wanted his family to know his true identity before it was too late. "I ain't gonna be around for more than a couple of years longer," he says. "So I figure whatever's gonna happen is gonna happen."

Matthews's story, which Newsweek verified through hundreds of FBI documents and several dozen interviews, including conversations with current and former FBI officials, offers a rare glimpse into the murky world of domestic intelligence, and the bureau's struggles to combat right-wing extremism.

No one can forget how Timothy McVeigh set off a bomb in front of a federal building in Oklahoma City in April 19, 1995, killing 168 people including 19 children under the age of 6. FBI efforts to avert another outrage have taken on increased importance in recent years, as fears of Islamic terrorism, a sour economy, expanded federal powers under the Patriot Act, and the nation's first black president have swelled the ranks of extremist groups. Since President Obama's election, the number of right-wing extremist groups—a term that covers a broad array of dissidents ranging from white supremacists to antigovernment militias—has mushroomed from 149 to 824, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Alabama-based civil-rights group.

"What we're seeing today is a resurgence," says Daryl Johnson, the former senior domestic terrorism analyst for the Department of Homeland Security. In 2009, the department issued a report warning that "right-wing extremism is likely to grow in strength." And because today's extremists, unlike their predecessors, have at their disposal online information—bomb-making instructions and terrorist tactics—as well as social-networking tools, the report said, "the consequences of their violence [could be] more severe."

The report, which was quickly withdrawn after an outcry from conservatives, seemed prescient months later when an 88-year-old gunman opened fire on visitors at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. Last year, nine members of the Hutaree, a Christian militia, were arrested in a plot to kill police officers in Michigan. In January, Jared Lee Loughner, an Army reject, was charged with going on a shooting rampage in Tucson, Ariz., killing a federal judge, among others, and severely wounding Arizona Rep. Gabrielle Giffords. Earlier this month, the FBI arrested four men of pensionable age in Georgia for allegedly plotting to attack federal buildings and release biological toxins on government employees.

In some ways, Matthews made the perfect FBI mole to go after these kinds of criminals. He is affable and chatty, without seeming to pry. And though over the years Matthews would come to realize that racism is wrong, he says that from an early age he had been steeped in the language of bigotry and extreme right-wing politics. Even today, Matthews occasionally lapses into epithets, though seemingly out of habit, not hatred, and sometimes with an apology. And unlike the extremists with whom he shared a fear of government, Matthews knew that an America controlled by radicals could be far worse.

"These people are just plain crazy," Matthews says. "If they don't like you, they [would] take you out to have you shot. They don't care. These people think that if they overthrew the government they'd make a better world. Their world would be a total nightmare."

Raised in the projects of Providence, R.I., and later in Northern California, Matthews was "one of those kids that quit high school … I wasn't happy where life was going and I wanted to be like John Wayne, so I joined the Marines." But Matthews's patriotism was jarred on his return from Vietnam to a country he felt showed no respect for what he sacrificed. He also noticed that many of his friends, exposed to Agent Orange in Vietnam, were getting sick. The sicker they got, the more Matthews distrusted those in power.

Initially unable to find work, Matthews joined the Rhode Island National Guard, then held a series of odd jobs—at a recycling plant in Piqua, Ohio, and as a tour guide at the Grand Canyon. Along the way he married and divorced four times. "The last one was the hardest," Matthews said. "We was together for 20 years. But I'm one of those guys who is like, 'If you think the grass is greener someplace else, go. I ain't gonna stop you.'"

Matthews, an ardent anticommunist, had long run in extremist circles, but an event in September 1990 opened his eyes to the dangers posed by the far right. It happened at a Las Vegas conference honoring Soldier of Fortune, a magazine popular with mercenaries and weapons enthusiasts. He went as a bodyguard to a Nicaraguan commander, and like many of the gun-toting men who gathered there that weekend, loved his country but hated his government: the economy was in tatters, the first Iraq War was imminent, and President George H.W. Bush was talking about the "New World Order."

At the conference, Matthews spent the mornings in seminars about surviving a government collapse and the afternoons firing automatic weapons at a local range. At night, participants gathered to play blackjack and talk politics.

One of the men Matthews hung out with that weekend was Tom Posey, the head of an American paramilitary group, once thousands strong, called the Civilian Material Assistance (CMA). In the 1980s, CMA, with encouragement from and the tacit support of the National Security Council and the CIA, had trained and armed anticommunist rebels in Nicaragua. (Ronald Reagan reportedly called Posey a "national treasure"; Oliver North, then a member of the NSC, hired a liaison to work with the network of private soldiers involved in the conflict, including the CMA.) After the war in Nicaragua ended, politics would quickly turn against Posey: as news spread that the U.S. had used networks of private soldiers to arm the contras, Posey was indicted for weapons smuggling. Though he beat the rap, he was stuck with considerable legal fees and a feeling, according to friends, that his government had hung him out to dry.

"During the contra war, I thought the world of Posey," says Matthews, who joined the CMA in 1985 and went to Nicaragua to help with the effort there. "He was a great man doing what he could to help the freedom fighters. But when the war was over, he had lost all his fame and all his glory. He was grasping for something."

On their last night on the Vegas Strip, two years after Posey's indictment, Posey and Matthews, both dressed in CMA uniforms, were sitting in a large banquet hall, smoking Marlboros and sipping Miller Lite, when, Matthews says, Posey leaned over and asked something he could hardly believe: Would he help Posey steal a cache of automatic weapons from the armory of the Browns Ferry nuclear plant in Alabama? Posey thought a second American Revolution was imminent, and he hoped to help fund it by selling off these weapons for profit. To make their getaway, Posey planned to set off a bomb in the plant's control room. Posey told Matthews he had spent part of the previous six months plotting this ambitious scheme, and, as Matthews would learn, he would continue to talk about it for the better part of three years.

As Posey spoke, Matthews nodded and smiled. But internally he was horrified. "I don't like radiation and I don't like chemicals," he tells Newsweek. "Sorry, I learned about that in the service."

Back at home, Matthews called the local office of the FBI. The next day, an agent arrived at his house and Matthews told him what he had heard. Days later, the same agent called Matthews: would he consider being an informant? The money wasn't great—$500 a week plus expenses—and the work could be dangerous. But Matthews felt he would be doing the right thing. Also, he says of the work, "being around crazy people, I guess I just felt normal. I felt at home."

Not long after he began working for the bureau, Matthews learned that Posey had called off his plans to rob Browns Ferry—the revolution didn't seem quite as imminent just then. Yet Posey had plenty of other illegal moneymaking schemes, and the connections to make them work.

And so beginning in the spring of 1991, and continuing for close to a decade, Matthews stayed undercover, traveling on a moment's notice, a stranger to his wife at the time and his five children from various marriages.

At the behest of his FBI handlers, Matthews—a wire often down his pants and a pistol in his shoulder holster—traveled across the country with Posey and others, attending dance parties with the Ku Klux Klan, selling weapons at truck stops and gas stations, sitting in church pews with would-be abortion-clinic bombers, and becoming a regular at gun shows and in paramilitary compounds. Extremist leaders were his frequent guests, sometimes staying the night, and hosted him when he traveled from home. "That's how well trusted I was. We was one big happy family," Matthews recalls.

It turned out that he was good at his job. "I learned a long time ago that you learn a lot more by sitting back and listening to people talk than you actually do trying to get involved. Ninety-nine percent of the people out there has a story they want to tell you or something they want to show you. And if you just sit back and listen and you go from place to place, they'll think you're somebody." Reflects one FBI official who worked with Matthews, "Informants never get the credit. They are always perceived as sleazy or dishonest, but you need people like [Matthews] to do a good job. He seemed genuine to me. He wanted to help."

Whenever Matthews returned home for a few days, he would connect with his FBI handler, a former Army intelligence officer named Donald Jarrett, a well-built African-American man who wore nice suits and kept his hair closely cropped. He would meet Matthews in abandoned parking lots or greasy spoons to talk strategy and to give Matthews his pay.

Matthews was assigned to Posey, who according to FBI documents was always scheming—from rather benign plots to counterfeit gold and silver coins to more dangerous ones like attempting to blow up gas and power lines in Alabama. He was a big talker, and they just didn't know if, when, and how he would put his plans into action.

Through Posey, Matthews met—and monitored—a who's who of the militia movement. One of Posey's cohorts in Arizona, for instance, planned to attack IRS agents with a homemade mortar gun. For months, Matthews traveled the country with this man, sharing motel rooms with him and networking with other right-wing extremists: "I'm out driving around with explosives in my truck, sleeping at nighttime with a .45 in my pillow because this guy I'm with is a total wacko," Matthews says. "He thought that all the missing kids in the United States were being abducted by aliens, and that aliens were putting them in big pots and eating 'em."

"I'd been in two wars," Matthews reflects, "but they was never like the war on domestic terrorism."

As Matthews was soon to learn, the FBI layered covert intrigue upon covert intrigue. In early 1992, Matthews says he and Posey traveled to Austin, Texas, to meet a former Klan leader and suspected member of a locally based paramilitary group, the Texas Reserve Militia (TRM). The FBI was investigating the TRM for allegedly laundering money through a Texas gun shop, paying off local law enforcement, purchasing stolen weapons from a military base, attempting to blow up a National Guard convoy in Alabama, and threatening to kill two FBI agents.

The suspected TRM member brought along a Vietnam veteran called Dave, an unremarkable-looking man in a green bomber jacket, fashionable among skinheads at the time. Matthews recalls that they met in a small, musty hotel room on the outskirts of the city, and for a few hours kicked back and talked about the movement. Posey went on about the New World Order, which to extremists like him meant the threat of global takeover by an assortment of international organizations including banks, the United Nations, and other elite institutions. Dave said he was the leader of a group of armored-car robbers who were using the proceeds of their exploits to fund the movement. "We were feeling each other out," Matthews says. "[Dave] let us know there was money available."

As the months passed, Matthews and Posey worked to connect high-ranking members of the movement to their new friend Dave. Eventually, however, Matthews began to wonder: if this guy has all this cash, and he's robbing all these armored cars, why haven't I heard about the robberies? Matthews asked Jarrett and several of his other handlers at the bureau and they demurred. Eventually, however, Matthews says Jarrett confirmed his suspicions: Dave was an undercover agent, traveling under a fake name. The hotel in Texas where they'd met had been bugged.

At first, Matthews felt betrayed. After all, Dave had known his status; it was as if the bureau didn't trust him. But Jarrett reassured him, and Matthews persevered. Now, when he and Dave arrived on a scene, they often would split up and had separate targets.

In September 1992, on a brisk morning in Benton, Tenn., Matthews met Dave and Posey at the annual convention of the American Pistol and Rifle Association, a gun-owners group to the right of the NRA. Matthews did his best to keep his distance from Dave. The atmosphere felt tense: guards dressed in camouflage uniforms and armed with semi-automatic pistols patrolled the compound. Matthews recalls children and adults firing at targets shaped like police cars at a nearby range. The disastrous standoff between federal agents and right-wing extremists at Ruby Ridge, Idaho—which had ended only the month before when an FBI sniper killed the wife of Randy Weaver as she held her baby daughter—had galvanized the radical right; men like Posey suddenly felt the New World Order was upon them, and talk was beginning to turn to action. ?

After the speech ended, Dave and Posey slipped out and walked through the grass to Posey's blue Ford Bronco. For months they had been trying to hash out a weapons deal. Posey had boasted to Dave that he could get him several Stinger missiles, priced at $40,000 apiece. That evening, though, Posey had only military-issued night-vision goggles in his SUV, serial numbers removed. Dave tried out several pairs, then handed $7,500 in cash to Posey. Before they parted, Dave asked Posey when he could get more goggles, and where they came from. Posey said he'd have them in about a week along with some TNT and C-4 explosives. The goggles, he said, came from "the black market."

By the spring of 1993, Posey seemed to believe that, once again, the revolution was at hand. Federal agents and religious separatists were in a standoff at a compound in Waco, Texas. Posey began having dreams, he told Matthews at the time, that God was directing him to lead a movement to overthrow the U.S. government. He revived his plan to rob the Browns Ferry armory in Alabama, and simultaneously ramped up a plot to take out gas and power lines nearby. For his part, Matthews was increasingly eager to intervene, although he knew that as an informant there was little he could do.

In some ways, he recalls some sympathy for Posey's hatred of government; Ruby Ridge and Waco had angered Matthews; they had heightened his fears of growing federal power. But Matthews didn't buy any of the extremists' New World Order nonsense. And he certainly didn't think the answer was killing police officers or FBI agents.

One Saturday morning in April, Matthews, Posey, and two of their cohorts were sitting in a McDonald's discussing the revolution. Suddenly, Posey noticed two men sitting in a car with the lights off, watching the restaurant. Infuriated, Posey and his friends piled into his car and started driving toward it.

"If it's the feds, what do we do?" one of Posey's friends asked.

"If it's the feds, we'll shoot them," Posey responded, taking out his pistol and putting it between his legs.

Trying to avoid suspicion, Matthews cocked his gun, but quickly began trying to persuade them not to attack. He knew there were FBI agents in the car; if Posey tried to fire on them, Matthews would have to kill Posey. By sheer luck, by the time Posey and company arrived, the agents were gone.

Over the next few months, Matthews tried to find ways to talk Posey and his young acolytes out of their revolutionary plans. Late one night in May, for instance, Matthews was sitting in the living room at Posey's house, chatting with Posey's teenage son, Marty. Earlier in the evening, Matthews and Posey had met at a friend's house and discussed training for the Browns Ferry robbery. A test run, Posey had said, would occur in two weeks.

With his father asleep, Marty Posey expressed his fear that he and his mother would lose their house if his father got caught. Matthews recalls telling Marty that he should say something to his father. Several days later, Matthews arrived at Posey's house and overheard Marty arguing with his father in the kitchen. "What happens, Dad, when they come and get you?" Marty said, according to an FBI report based on Matthews's statements. (Marty Posey says he does not recall this conversation.)

By September 1993, however, Posey was still moving forward on his plans to rob the Browns Ferry armory and to take out gas and power lines nearby. A five-man team would break into the armory using bolt cutters and steal the weapons. They had already befriended several of the guards, who Matthews says had signed on to help.

The bureau, realizing that the lines were in fact vulnerable, decided to act. Hoping to avoid a repeat of the disastrously heavy-handed raid at Waco, Jarrett called Matthews, asking for his advice on when Posey would most likely be unarmed. Matthews told him Posey always left his pistol in his glove compartment when he went to mail a package. On Sept. 9, a team of FBI agents surrounded Posey at a post office in Decatur, Ala. True to form, Posey did not have a weapon on him and surrendered immediately.

After Posey's arrest, the FBI had Matthews's Social Security number changed and paid for him and his family to move to Stockton, Calif. They also flew him to Montgomery, Ala., for Posey's trial. Despite hundreds of hours of recorded conversations, as well as video and personal surveillance, the district attorney's office had chosen to prosecute Posey and his cohorts only for buying and selling the stolen goggles. A spokeswoman for the U.S. attorney's office in the Northern District of Alabama said there had been insufficient evidence for anything else.

Matthews remembers several FBI agents in suits greeting him at the airport, and they rode in a motorcade—three large sedans with black-tinted windows—to the courthouse. There Matthews, in a brown blazer and tie, his hair neatly combed, entered through the garage, surrounded by the G-men. As he entered the old courtroom, Matthews could see the disgust on Posey's face and he felt his heart quicken. "I was scared," he says. "You always get scared in court. You don't wanna screw up your words [and] you hope everybody believes you."

The prosecutor questioned Matthews on his dealings with Posey and Dave and the sale of the goggles. He played several recordings that backed his account. And then Matthews stepped off the stand. The FBI agents escorted him out of the courtroom the same way he came in. Hours later, he was on a plane back to Arizona. In the end, Posey was sentenced to just two years in prison and fined $20,000.

One afternoon earlier this year, Matthews was sitting on the couch in his Reno apartment, thinking back on his life. In the kitchen hung a plaque from the FBI: "John W. Matthews: In appreciation and recognition for your outstanding efforts in assisting the FBI to combat domestic terrorism throughout the United States: March 28, 1991–May 30, 1998."

It had been a hell of a decade since he quit the job. In 2001, his son Kern, suffering from cerebral palsy, died at the age of 8. Then his 20-year marriage fell apart as he and his wife coped with the death. Soon thereafter, the effects of Vietnam on Matthews's body became increasingly clear: the Agent Orange he was exposed to had left his heart weakened and given him diabetes; asbestos from his military days had wrought havoc on his lungs. In 2008 he went into the hospital for a colonoscopy; he began to bleed uncontrollably; his heart stopped—twice—and doctors twice brought him back.

After another stint in the emergency room this year, Matthews says he kept thinking about what his family knew about him and what he had sacrificed over the years. He started to wonder if anyone had ever tied his name to the FBI. On a whim, he began searching around online.

He found an article about Jesse Trentadue, the Salt Lake City attorney who for 15 years had been filing profanity-laced letters and Freedom of Information Act requests to federal agencies in order to prove that the FBI killed his brother, Kenney, during a botched interrogation in Oklahoma City not long after McVeigh's bombing of the federal office building there. Trentadue and his family were awarded roughly $1 million for emotional distress after the Justice Department found that the FBI and Bureau of Prisons had lied in court and ignored and misplaced evidence during the investigation.

Trentadue believed that the FBI had confused Kenney for a member of a gang of white supremacist bank robbers called the Aryan Republican Army; though for years the FBI has claimed that McVeigh largely acted alone, Trentadue has uncovered evidence allegedly linking him to the ARA and the group to the bombing.

As Matthews read on he ran across a name that stopped him cold: his own. Some of the documents that Trentadue had put online mentioned Matthews, and in a few places, the FBI had failed to redact it. "All those years I've been a good boy and kept my mouth shut," Matthews says. "Then you release my name? What kind of shit is that?"

And so, angry and feeling he might be able to help Trentadue, Matthews asked his son Dan to drive him to the lawyer's office in Salt Lake City. Considering his health, he no longer cared about the repercussions—whether from the FBI or the bad guys. His kids, he believed from years of observing how right-wing extremists operated, would be safe.

On the morning in July when he met Trentadue, Matthews and Dan sat at a large wooden table in the attorney's office. For several hours they spoke about Trentadue's suits against the FBI, and Matthews reminisced about his time in the bureau, explaining to his son the various plots and villains that he encountered and why he was never around.

Eventually, they got up to leave. Outside the sun was bright and the air was warm. As they cruised along in a silver SUV, Matthews and Dan said little. Only now, the silence was full, and each felt they had asked and answered their part.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Ross Schneiderman started as an intern at Newsweek in 2005. He worked as a reporter-researcher at the magazine in 2006 ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.