Archaeologists believe they have found the key to unlocking a mystery millennia in the making, uncovering how advanced civilizations in the lands of the Bible were invaded by so-called "sea people" in 1190 B.C., bringing an end to the Bronze Age.

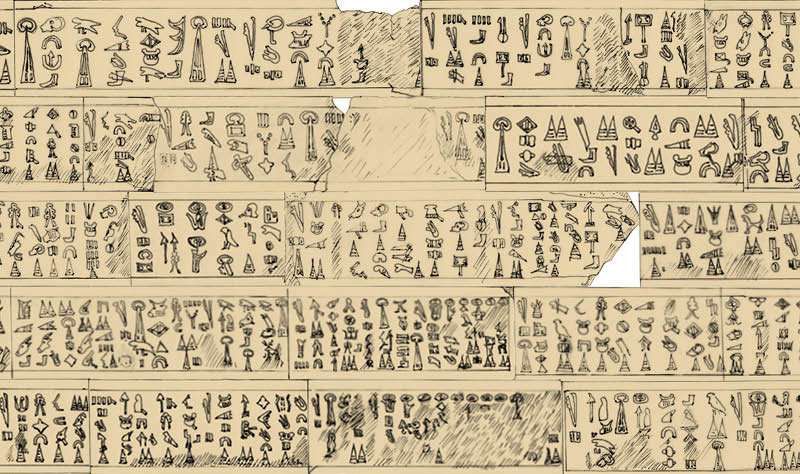

Researchers finally unravelled the secret studying inscriptions first discovered over 100-years-ago. A team of Swiss and Dutch archaeologists from the Luwian Studies Foundation rediscovered the writings from the largest Bronze Age tablet ever found, translating it for the first time and revealing the unexplained history.

Related: Ancient Tomb of Santa Claus Discovered Beneath Turkish Church

The nearly 95-foot-long limestone frieze was first found in Turkey in 1878 by French archeologist Georges Perrot and while the tablet was destroyed, Perrot was able to copy the inscription before it was lost.

It was not until 1950 that studies advanced sufficiently for the Luwian hieroglyphs, the official recorded language of the peoples of ancient south eastern Turkey, to be read.

They revealed the tablet was commissioned by King Kupanta-Kurunta, the ruler of a Late Bronze Age state in western Asia Minor whose forces flooded east annexing lands loyal to the Hittite civilisation in Anatolia.

Following the conquest, Kurunta's men took to the sea in a fleet of ships with other local forces. These so-called "sea people," led by four princes, invaded a number of ancient coastal centers in modern day Syria and Israel, building a fortress in Ashkelon and eventually advancing as far as ancient Egypt.

The account in the stone tablet reveals how Bronze Age civilizations disappeared from the eastern periphery of the Mediterranean, one of the long unsolved puzzles of archaeology from the region.

The new discovery has relied greatly on the work of a team of Turkish and U.S. experts to translate the 19th Century inscription after it made its way into the collections of the Ottoman Empire. Following delays, by the time the copies of the inscriptions were finally published in 1985 the entire original team of researchers had died.

It was not until they were rediscovered in the estate of English prehistorian James Mellaart, who died in 2012, that the legacy was passed on to the Swiss geoarcheologist Dr. Eberhard Zangger, president of the Luwian Studies foundation, to edit and publish the material.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Callum Paton is a staff writer at Newsweek specializing in North Africa and the Middle East. He has worked freelance ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.