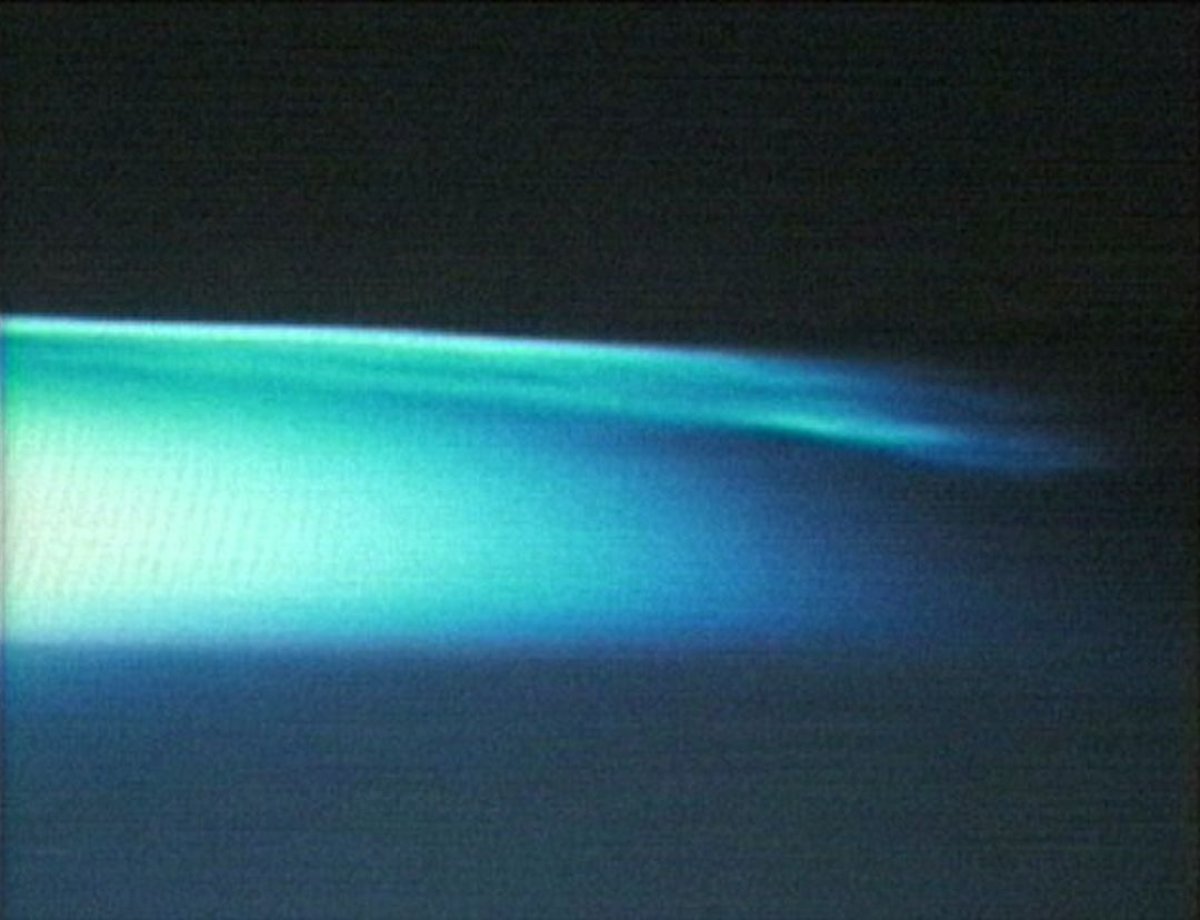

Photographs of incredible "electric blue clouds" have been released by NASA, having been taken by a space agency balloon hovering 50 miles above the surface of Earth.

These noctilucent clouds, or polar mesospheric clouds (PMCs), sit at the edge of Earth's atmosphere. The new images, from NASA's PMC Turbo mission, show the "brilliant blue" rippling clouds in incredible detail.

PMCs appear about 50 miles above the poles during summer. They form as ice crystals on the remnants of meteors in the upper atmosphere and the blue ripples can be seen just after the sun sets in the polar regions.

Scientists want to study PMCs because they are affected by atmospheric gravity waves, which is caused by air convection and uplift. These waves are involved in the transference of energy from the lower atmosphere to the mesosphere, an area above the stratosphere and below the thermosphere—about 30 and 50 miles in altitude.

The PMC project involved sending a balloon up into the atmosphere to study these clouds over five days. The balloon traveled from its launch site in Sweden across the Arctic all the way to Canada.

"This is the first time we've been able to visualize the flow of energy from larger gravity waves to smaller flow instabilities and turbulence in the upper atmosphere," Dave Fritts, principal investigator on the mission, said in a statement. "At these altitudes you can literally see the gravity waves breaking—like ocean waves on the beach—and cascading to turbulence.

Scientists have just started to analyze the photos from PMC Turbo—six million high resolution images. As well as giving a better insight into the goings on in the atmosphere, the results should allow researchers to improve weather forecasts. "From what we've seen so far, we expect to have a really spectacular dataset from this mission." Fritts said. "Our cameras were likely able to capture some really interesting events and we hope will provide new insights into these complex dynamics."

For many years, PMCs were something of a puzzle. In 2003, scientists on board the International Space Station observed the "glowing electric blue" clouds, releasing images showing them from 250 miles above Earth's surface. At the time, researchers did not know if they were caused by space dust or by global warming.

PMCs were first observed in 1885 two years after a huge eruption at Indonesia's Krakatoa volcano. In the aftermath, skywatcher T. W. Backhouse noticed electric blue wispy filaments glowing in the sky after the sun had set. These observations led scientists at the time to believe the clouds were somehow a manifestation of volcanic ash.

Fritts told Newsweek: "

When they were first documented in 1885, and recognized to be at a very high altitude, their origin and structure were a mystery. Sydney Chapman initially speculated that they might be dust particles, but in a subsequent publication in 1965, argued that they were formed on dust particles but were largely ice. This interpretation as ice particles is now well accepted based on many observations and modeling studies.

"We are very pleased with the data we have obtained during our PMC Turbo flight from Sweden to Canada. We believe these data will enable many useful insights into the dynamics revealed in the PMC motions we observed. If that proves to be the case, yes, we do plan to propose another flight with the same imagers, but which we would also plan to upgrade with addition of a second lidar and a second telescope that would enable more complete measurements of the atmospheric structures in which the PMCs evolve."

This article has been updated to include quotes from David Fritts.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Hannah Osborne is Nesweek's Science Editor, based in London, UK. Hannah joined Newsweek in 2017 from IBTimes UK. She is ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.