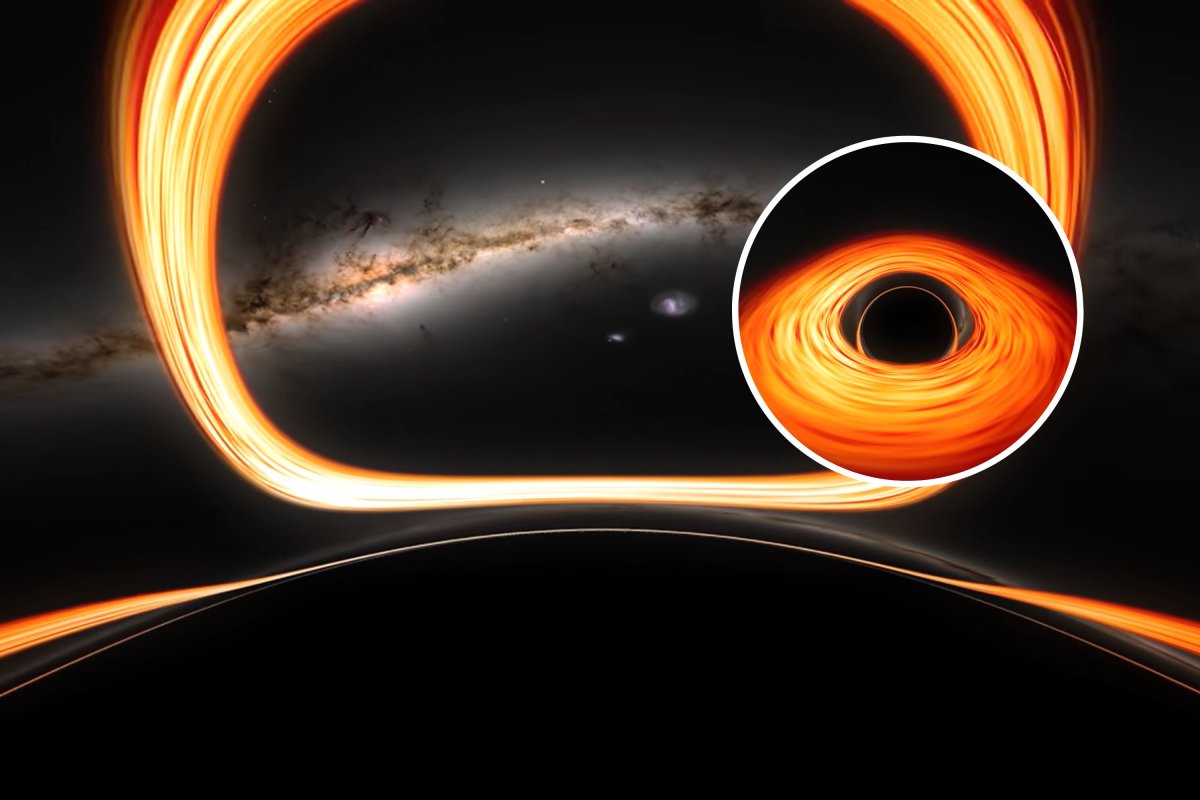

In a new video straight out of the movie Interstellar, NASA has revealed what it might look like to fall into a black hole.

The simulation was created using a NASA supercomputer, and imagines what a person might see as they plummet past a black hole's event horizon into the abyss beyond.

Another simulation shows what a person flying past a black hole would see, with space appearing to bend and twist as the viewer zooms past.

"I simulated two different scenarios, one where a camera—a stand-in for a daring astronaut—just misses the event horizon and slingshots back out, and one where it crosses the boundary, sealing its fate," simulation creator Jeremy Schnittman, an astrophysicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in a statement.

Black holes are objects that have a gravitational pull so strong that not even light can escape from them. There are several types, including stellar black holes (formed by the collapse of individual stars) and supermassive black holes (found at the centers of most galaxies, including the Milky Way). Every black hole has an event horizon, which is the boundary around a black hole beyond which no light or other radiation can escape.

The black hole in the NASA simulation is a supermassive black hole, like the one at the center of our galaxy, with a mass around 4.3 million times that of our sun and an event horizon of about 16 million miles across. The bright ring of gas around the black hole is known as the accretion disk, which glows brightly due to the large amount of heat generated by friction.

The simulation shows the viewer starting around 400 million miles away from the black hole and rapidly falling towards it, with the accretion disc becoming distorted and warped as the viewer approaches.

"If you have the choice, you want to fall into a supermassive black hole," Schnittman said. "Stellar-mass black holes, which contain up to about 30 solar masses, possess much smaller event horizons and stronger tidal forces, which can rip apart approaching objects before they get to the horizon."

This is because the force of gravity exerted on your body would be stronger at your feet than at your head, stretching you out atom by atom in a process known as spaghettification.

"A stellar-mass black hole has such extreme tidal forces outside of its event horizon (an astronaut falling feet first would feel stronger gravity at their feet than their head) that our astronaut would be torn apart well before reaching the event horizon," Ben Farr, a physicist and gravitational wave astronomer at the University of Oregon, previously told Newsweek. "Tidal forces are felt by an object when the force of gravity it experiences from some massive object is stronger on one of its sides than the other."

For this simulated black hole, the viewer would have only 12.8 seconds before being destroyed by spaghettification.

The other simulation shows a viewer orbiting close to the event horizon but not quite crossing it. A person coming this close to a black hole of this size would return 36 minutes younger than those who stayed further away, due to the difference in the speed of time passing near an object with such large gravity.

"This situation can be even more extreme," Schnittman said. "If the black hole were rapidly rotating, like the one shown in the 2014 movie Interstellar, she would return many years younger than her shipmates."

These simulations were made using the Discover supercomputer at the NASA Center for Climate Simulation, and take up around 10 terabytes of data.

"People often ask about this, and simulating these difficult-to-imagine processes helps me connect the mathematics of relativity to actual consequences in the real universe," Schnittman said.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about black holes? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more