The very word "slavery" brings to mind African bodies stuffed in the hold of a ship or white-aproned maids bustling in an antebellum home. Textbooks, memoirs, and movies continuously reinforce the notion that slaves were black Africans imported into the New World.

We may be aware that in the long sweep of history, peoples other than Africans have been held in bondage—a practice that continues today as millions of Asians, hundreds of thousands of Latin Americans and thousands of Europeans can readily attest. But we still seem unable to escape our historical myopia.

Consider the debate at the conclusion of the U.S.-Mexican War of 1846–1848. The United States had just acquired Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah, more than half of Colorado and parts of Wyoming and Kansas. The question facing the country was whether slavery should be allowed in this vast territorial haul.

By slavery, of course, politicians of that era meant African slavery. But the adjective was wholly unnecessary, as everyone in the United States knew who the slaves were.

Therefore it came as a revelation to many easterners making their way across the continent that there were also Indian slaves, entrapped in a distinct brand of bondage that was even older in the New World, perpetrated by colonial Spain and inherited by Mexico. With the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo at the end of the war, this other slavery became a part of Americans' existence.

California may have entered the Union as a "free-soil" state, but American settlers soon discovered that the buying and selling of Indians was a common practice there.

As early as 1846, the first American commander of San Francisco acknowledged that "certain persons have been and still are imprisoning and holding to service Indians against their will" and warned the general public that "the Indian population must not be regarded in the light of slaves." His pleas went unheeded.

The first California legislature passed the Indian Act of 1850, which authorized the arrest of "vagrant" Natives who could then be "hired out" to the highest bidder. This act also enabled white persons to go before a justice of the peace to obtain Indian children "for indenture."

According to one scholarly estimate, this act may have affected as many as 20,000 California Indians, including four thousand children kidnapped from their parents and employed primarily as domestic servants and farm laborers.

Americans learned about this other slavery one state at a time. In New Mexico, James S. Calhoun, the first Indian agent of the territory, could not hide his amazement at the sophistication of the Indian slave market.

"The value of the captives depends upon age, sex, beauty, and usefulness," wrote Calhoun. "Good looking females, not having passed the 'sear and yellow leaf,' are valued from $50 to $150 each; males, as they may be useful, one-half less, never more."

Calhoun met many of these slaves and wrote pithy notes about them: "Refugio Picaros, about twelve years of age, taken from a rancho near Santiago, State of Durango, Mexico two years ago by Comanches, who immediately sold him to the Apaches, and with them he lived and roamed . . . until January last [1850], when he was bought by José Francisco Lucero, a New Mexican residing at the Moro."

"Teodora Martel, ten or twelve years of age, was taken from the service of José Alvarado near Saltillo, Mexico by Apaches two years ago, and has remained the greater portion of the time on the west side of the Rio del Norte."

Americans settling the West did more than become familiar with this other type of bondage. They became part of the system.

Mormon settlers arrived in Utah in the 1840s looking for a promised land, only to discover that Indians and Mexicans had already turned the Great Basin into a slaving ground. The area was like a gigantic moonscape of bleached sand, salt flats, and mountain ranges inhabited by small bands no larger than extended families.

Early travelers to the West did not hide their contempt for these "digger Indians," who lacked both horses and weapons. These vulnerable Paiutes, as they were known, had become easy prey for other, mounted Indians.

Brigham Young and his followers, after establishing themselves in the area, became the most obvious outlet for these captives. Hesitant at first, the Mormons required some encouragement from slavers, who tortured children with knives or hot irons to call attention to their trade and elicit sympathy from potential buyers or threatened to kill any child who went unpurchased.

Brigham Young's son-in-law Charles Decker witnessed the execution of an Indian girl before he agreed to exchange his gun for another captive. In the end, the Mormons became buyers and even found a way to rationalize their participation in this human market.

"Buy up the Lamanite [Indian] children," Brigham Young counseled his brethren in the town of Parowan, "and educate them and teach them the gospel, so that many generations would not pass ere they should become a white and delight- some people." This was the same logic Spanish conquistadors had used in the sixteenth century to justify the acquisition of Indian slaves.

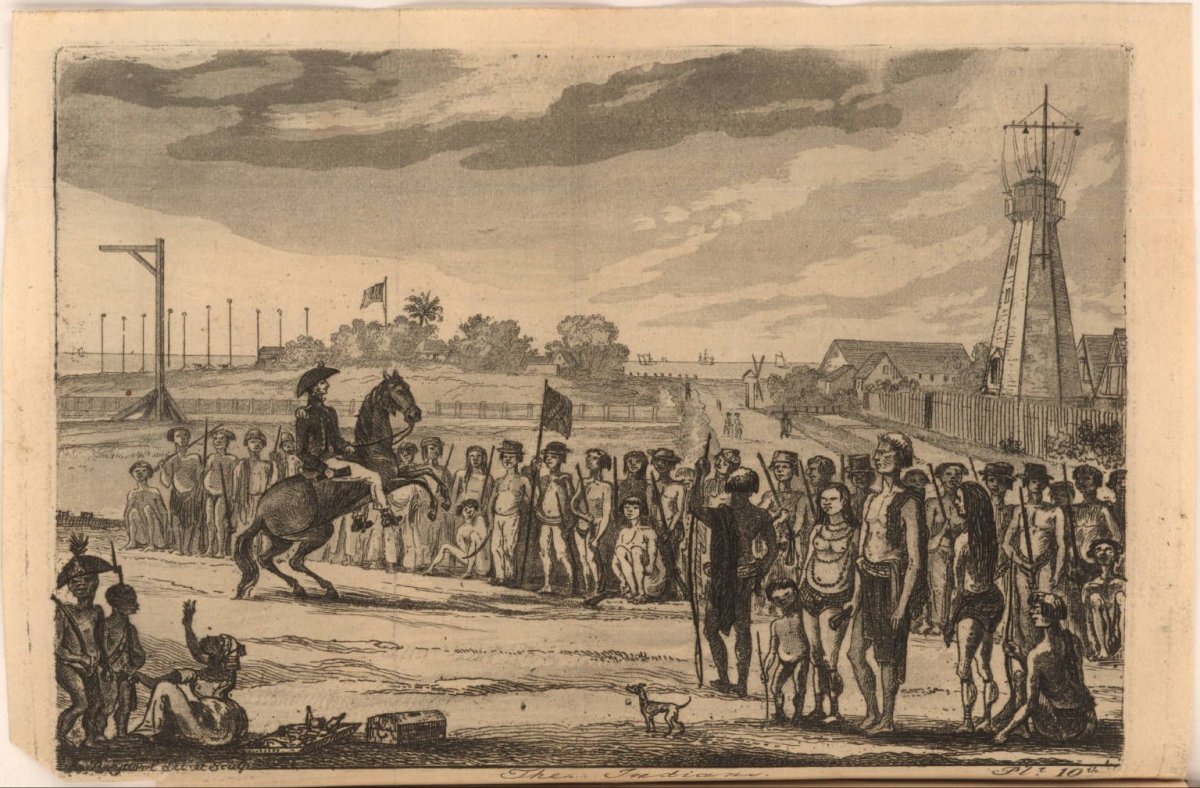

The beginnings of this other slavery are lost in the mists of time. Native peoples such as the Zapotecs, Mayas and Aztecs took captives to use as sacrificial victims; the Iroquois waged campaigns called "mourning wars" on neighboring groups to avenge and replace their dead; and Indians in the Pacific Northwest included male and female slaves as part of the goods sent by the groom to his bride's family to finalize marriages among the elite.

Native Americans had enslaved each other for millennia, but with the arrival of Europeans, practices of captivity originally embedded in specific cultural contexts became commodified, expanded in unexpected ways, and came to resemble the kinds of human trafficking that are recognizable to us today.

The earliest European explorers began this process by taking indigenous slaves. Columbus's very first business venture in the New World consisted of sending four caravels loaded to capacity with 550 Natives back to Europe, to be auctioned off in the markets of the Mediterranean.

Others followed in the Admiral's lead. The English, French, Dutch and Portuguese all became important participants in the Indian slave trade. Spain, however, by virtue of the large and densely populated colonies it ruled, became the dominant slaving power. Indeed, Spain was to Indian slavery what Portugal and later England were to African slavery.

Ironically, Spain was the first imperial power to formally discuss and recognize the humanity of Indians. In the early 1500s, the Spanish monarchs prohibited Indian slavery except in special cases, and after 1542 they banned the practice altogether.

Unlike African slavery, which remained legal and firmly sustained by racial prejudice and the struggle against Islam, the enslavement of Native Americans was against the law. Yet this categorical prohibition did not stop generations of determined conquistadors and colonists from taking Native slaves on a planetary scale, from the Eastern Seaboard of the United States to the tip of South America, and from the Canary Islands to the Philippines.

The fact that this other slavery had to be carried out clandestinely made it even more insidious. It is a tale of good intentions gone badly astray.

When I began researching my book "The Other Slavery," one number was of particular interest to me: how many Indian slaves had there been in the Americas since the time of Columbus?

My initial belief was that Indian slavery had been somewhat marginal. Even if the traffic of Indians had flourished during the early colonial period, it must have gone into deep decline once African slaves and paid workers became available in sufficient numbers.

Along with most other historians, I assumed that the real story of exploitation in the New World involved the 12 million Africans carried off across the Atlantic. But as I kept collecting sources on Indian slavery in Spanish, Mexican and U.S. archives, I began to see things differently.

Indian slavery never went away, but rather coexisted with African slavery from the sixteenth all the way through the late nineteenth century. This realization made me ponder more seriously the question of visibility.

Because African slavery was legal, its victims are easy to spot in the historical record. They were taxed on their entry into ports and appear on bills of sale, wills, and other documents. Because these slaves had to cross the Atlantic Ocean, they were scrupulously — one could even say obsessively — counted along the way.

The final tally of 12.5 million enslaved Africans matters greatly because it has shaped our perception of African slavery in fundamental ways. Whenever we read about a slave market in Virginia, a slaving raid into the interior of Angola, or a community of runaways in Brazil, we are well aware that all these events were part of a vast system spanning the Atlantic world and involving millions of victims.

Excerpted from The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America © 2016 by Andrés Reséndez. Reproduced by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.