Scientists have uncovered evidence of lead exposure in the teeth of two Neanderthal children that lived 250,000 years ago. This is the oldest documented exposure to lead among hominins and indicates this ancient group was ingesting contaminated food or water from some unknown source at certain points in their lives.

Researchers led by Tanya Smith, from Australia's Griffith University, were investigating two infant teeth discovered at the French Neanderthal site Payre. They were looking to find out what life would have been like for Neanderthals as the seasons changed and how they adapted during winter months, when food was scarce.

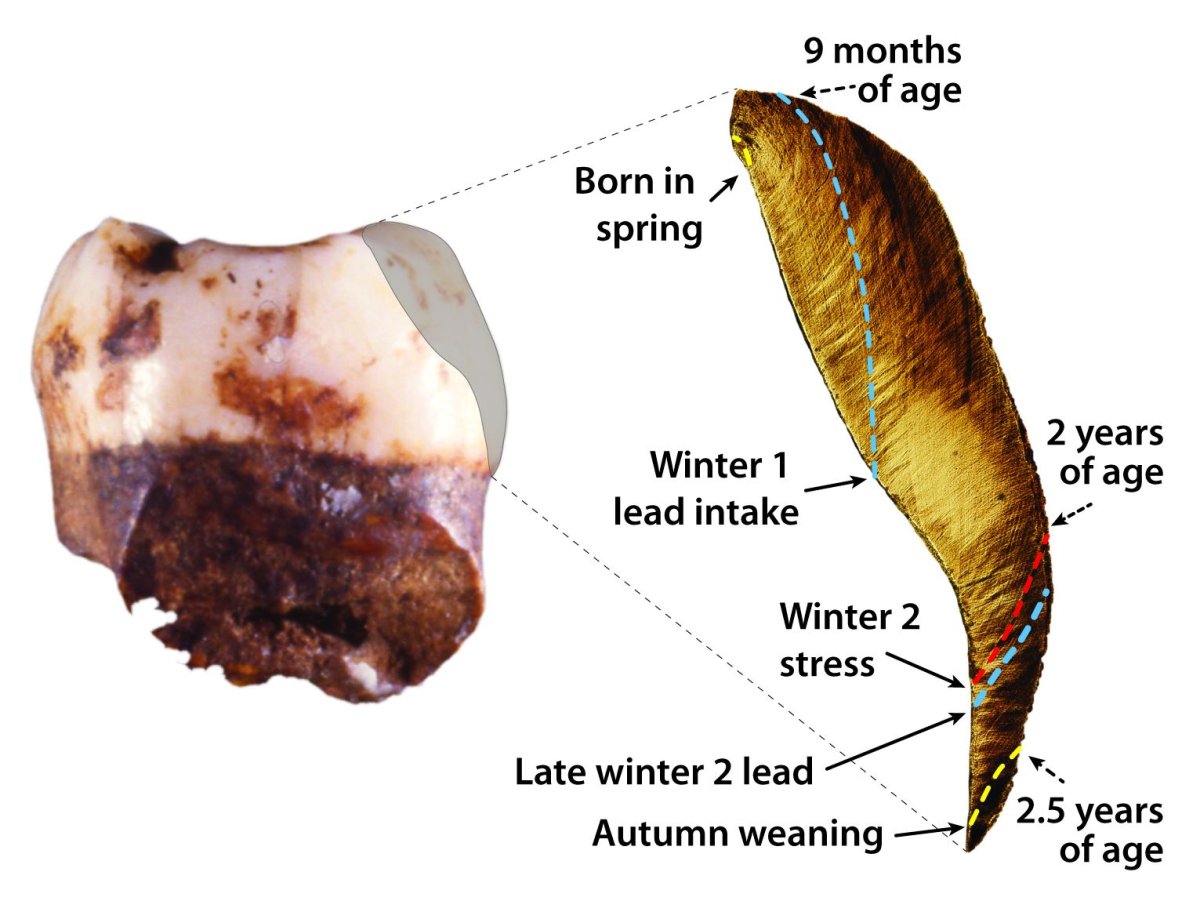

Children's teeth serve as a useful tool in building up a picture of the environment in which they lived. This is because a new tooth layer is formed every day, eventually building up "growth rings" that contain information about what they were being exposed to over different points in their lives.

In the latest study, published in Science Advances, researchers have uncovered new information about wintertime stresses, nursing and weaning practices, and exposure to lead in the environment. Findings showed that one of the Neanderthal children was born in the spring and weaned in the fall at the age of two-and-a-half. Both children had periods of sickness and these normally took place during the colder months.

Both were also exposed to lead for short intervals as they were growing up—a discovery that surprised Smith. "We've really only been aware of humans being exposed to lead more recently, and typically in the context of metallurgy," she told Newsweek. "The site where these Neanderthals were discovered is within 15 miles of historic commercial lead mines. While we can't be sure, one possibility is that Neanderthal groups used these caves, and/or consumed contaminated water or food nearby."

Lead exposure in children has been linked to cognitive impairment and behavioral problems, as well as a range of physical problems. "They didn't show obvious disruptions in their teeth—which can occur with high levels of lead—but there isn't any safe level for humans or other animals," Smith said. "We can't know if these exposures had any effect on their brain development or cognition."

The researchers also compared the Neanderthal teeth to one from another ancient hominin that lived at the same site around 150,000 years later. This allowed them to compare the climates in which the two species lived. They found the winters the two Neanderthal children lived through appeared to be colder and harsher than that of the later hominin. They also did not find exposure to lead in the later tooth sample.

Archaeologist James Cole, from the U.K.'s University of Brighton, who was not involved in the research, said the findings provide a "welcome glimpse into what daily life must have been like for our Neanderthal ancestors." He said the detailed life history the study provides is a "remarkable insight" into the ways of life 250,000 years ago. "That is just astonishing," he told Newsweek. "In addition, the Payre 6 [one of the children] Neanderthal seems to have fallen acutely ill around two years of age where the individual nursed throughout the episode."

"Gaining insights into the Neanderthal life history… really helps us to understand where we have come from and how similar, or not, to our own life history our human ancestors may have been. Only by understanding the past and our interactions with our human ancestors can we hope to understand the future of our species and how to build a more inclusive and diverse future."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Hannah Osborne is Nesweek's Science Editor, based in London, UK. Hannah joined Newsweek in 2017 from IBTimes UK. She is ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.