The gossip website Gawker was nasty, condescending, petty, trivial, too cool for school, annoyingly progressive, stunningly retrograde, obsessed with celebrity, contemptuous of celebrity, tormentor of Fox News and The New York Times alike, full of itself, full of shit, too earnest, too cynical, not real journalism, a waste of time, the reason they hate us, whoever they are.

I loved Gawker, and I read it every single day, usually more than once. The one time it made fun of me, I was thrilled, because if it hadn't taken a predictably caustic note of your work, you were probably still some anonymous scribe for the Palookaville Daily Bugle. For those of us in the decreasingly glamorous business of journalism, Gawker was the bar right before last call with every ambitious and angry hack in town. The hour is getting late, and nobody is saying "Now, this is off the record" anymore. Everything is on the record, and everything is fair game, from the sins of Bill Cosby to the untouched Vogue photos of Lena Dunham. Both of those were Gawker stories, which in part helped them become stories elsewhere.

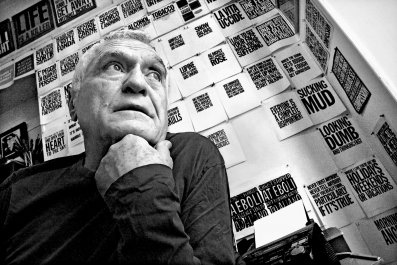

A barstool heart-to-heart was, in fact, how Nick Denton, who founded Gawker in 2002, described the whole enterprise (which would come to include several affiliate sites, most notably Jezebel, Deadspin, Gizmodo and Lifehacker) to The Hollywood Reporter in 2013: "The basic concept was two journalists in a bar telling each other a story that's much more interesting than whatever hits the papers the next day," he said. You could read the fawning profiles of Tom Cruise, or you could read about his disturbing work on behalf of the Church of Scientology. If you wanted the latter, you wanted Gawker.

The bar closed last year, with Gawker shut down and its remaining properties sold for scrap to to Univision Communications, a growing media empire with a 40% stake in satire site The Onion and ownership of Fusion, Gawker's former rival and stooge. "More people work at Fusion than are reading its most popular post," ran one Gawker story in 2015. Now many of its journalists work there .

The short story has to do with Hulk Hogan's penis. So does the long story, as it were. In 2012, the site published an excerpt from a video in which the professional wrestler, whose real name is Terry Gene Bollea, is seen having sex with Heather Clem, the wife of a friend. Bollea sued for invasion of privacy in a Florida court and won.

The Netflix documentary Nobody Speak: Trials of the Free Press , written and directed by Brian Knappenberger, is the story of that trial, which took place last spring and was open to the media and captured by cameras, à la O.J. Simpson, only with color photographs of bodies in deathly repose replaced by grainy footage of bodies in flagrante delicto . At one point, Hogan takes the stand and, under the seal of the great state of Florida, explains that while Hulk Hogan may have a 10-inch penis, his mortal counterpart, Bollea, does not. At issue was the tension between Hulk Hogan, public persona, and Hulk Hogan, private citizen. Lawyers for Bollea argued that publication of the sextape infringed on his privacy, discounting the journalistic value of the tape. The jury agreed, and how, awarding him $115 million in damages. The judge added another $25 million for good measure.

When I later profiled Bollea's lead lawyer on the case, the high-profile Los Angeles attorney Charles Harder, he was unrepentant about being depicted as the man who killed Gawker. Some were branding him as an enemy of the First Amendment itself. That didn't bother Harder, either. At the heart of the matter was decency, as well as journalistic responsibility to know what belongs in print and what does not. As he told me nonchalantly over lunch, "If it has a chilling effect on irresponsible journalism? Awesome!"

Nobody Speak is the counter-argument to that assertion. The documentary, for the most part, treats the Gawker crew with unwavering sympathy, assuming perhaps too readily that viewers share a similar belief about the inherent rightness of its actions. The documentary opens with A.J. Daulerio, Gawkers one-time editor-in-chief and the writer who published the offending post, discussing his bankruptcy. On his laptop, he shows a $230 million hold on his bank account, based on his own liability in the case.

"This is just something that I'm caught in the middle of," Daulerio says. He's caught, that's for sure, but he was not a helpless bystander in the drama that came to be known as Hulk vs. Gawk. Nor was the Hogan sex tape his first irresponsible, salacious post. As others have noted, irresponsible, salacious posts were his métier.

Gawker on Golgotha is a compelling image, but it's not an entirely accurate one. As the site shut down, it became a kind of cause célèbre on social media, lamented by many of the same people who, only months ago, derided it for a flagrantly unethical post about the sex life of a prominent New York media executive. As a matter of fact, Gawker had long harbored a discomfiting curiosity about the sex lives of others; in 2013, New York Times media columnist David Carr blasted Gawker for its "moralistic and invasive" obsession with the sexual orientation of Fox News broadcaster Shepard Smith.

It's not that Gawker deserved to be destroyed, it just wasn't the champion of journalistic freedoms the film makes it out to be. In fact, it did a lot of things a traditional outlet wouldn't do, such as paying sources, publishing nudes (of celebrities and non-celebrities alike) and engaging in ad hominem attacks. It wanted to have it both ways, old journalism respectability with new journalism freedoms. In the end, that tightrope proved impossible to walk.

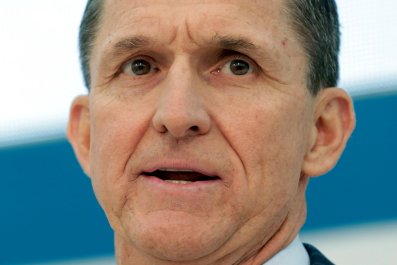

The true villain of Nobody Speak is not Bollea, who comes across as a fading celebrity tending to middle-age bloat. Rather, it is the Silicon Valley billionaire Peter Thiel, who was eventually revealed to have funded the Bollea suit, as well as several others against the site, part of a longstanding grievance for having been outed as gay by a defunct Gawker property called Valleywag.

Nobody Speak plainly makes the case that Thiel's pursuit of Gawker was unfair, motivated by an acute case of thin skin. But what exactly did Thiel do that was so wrong? Certainly, it is not illegal to pay lawyers' fees, nor to keep quiet about having made such payments. It was a jury of ordinary Floridians that decided Gawker's fate, not some cold-blooded Silicon Valley billionaire. The Gawker staffers interviewed in this case don't seem to grasp that fact, striking a jarring note of self-righteousness.

Back when Gawker was being laid to rest, editor John Cook had mystifyingly compared its demise to that of the Khans, the Gold Star parents who'd bravely spoken out during the Democratic National Convention. He is a little less tone deaf in Nobody Speak, but remains inclined to see himself as a Woodward and Bernstein figure, not the man who once published a post titled "That U.S. Olympic Rower's Cock Is Not Giant: A Photoanalysis," to which I will spare you a link. In many ways, it was Cook's site that was felled, not the far more successful and entertaining version of Gawker presided over by founding editor Elizabeth Spiers and, later, Jessica Coen and Emily Gould (in general, the site was best when led by a woman).

Thiel is an avis rara for several reasons, one of them being that he is a more-or-less openly gay, highly educated Silicon Valley entrepreneur who just happens to be a Trump supporter. The film uses Thiel to nimbly pivot towards Trump and the right's war on the free press, which began in earnest around the same time that the Gawker case was winding down.

Paradoxically, this Gawker documentary is most successful when it leaves Gawker aside for what are, frankly, more relevant cases of transgressions on freedom of the press: the purchase of the Las Vegas Review-Journal by the gaming billionaire and Republican megadonor Sheldon Adelson, who did his best to hide his involvement in the purchase, and the unceasing attacks against the Fourth Estate by Trump, including a desire to "open up" libel laws. Along with the need for a border wall, his conviction that the press is the "enemy of the people" may constitute the entirety of Trumpism. And since the wall is gone, it may be that his sole guiding idea is a hatred of the press.

Gawker's demise does not quite seem as serious as these transgressions, nor as entirely shocking. The site was undone by its own madcap brilliance, like the barroom raconteur enthralling after two drinks, unbearable after four. Especially near the end, when it was edited by Max Read (an otherwise skilled journalist) and the self-important Cook, the site seemed to descend into embittered pomposity, unable to see that it had long ceased to be either the darling or the underdog. In one of those ironic tricks time plays on us, it had become the very kind of bully it used to slay.

For all that, I miss Gawker terribly. It's sad that it died right on the cusp of Trump's presidency, that its final energy was expended on what seems, now, the relative calm of the Obama years. Although some of Gawker's finest journalists — Hamilton Nolan, J.K Trotter, among many others — continue on as Fusion employees, they no longer have their best and loudest megaphone. That's a shame, because while Gawker could be an irritant, it could also be a truth-teller. The two are sometimes hard to separate.