Updated | Finding out if you have one of eight cancers could someday be as simple as having your blood drawn, thanks to a new test. For five of these cancers, the test, called CancerSEEK, would be the first-ever screening of its kind to become available. It could even literally save lives by detecting early-stage cancers, including hard-to-detect ones like pancreatic cancer.

Researchers from across the United States, as well as Italy and Australia, published a paper demonstrating the test's capabilities in Science on Thursday. The study, which screened over 1,000 patients known to have cancer and 815 people presumed to be healthy, found that the test could accurately detect cancer when it existed about 70 percent of the time and accurately did not detect cancer more than 99 percent of the time. The test also gave doctors clues about where to look for a tumor in about 83 percent of the cases used. The types of cancers that could be detected include ovarian, liver, stomach, pancreatic, esophageal, colorectal, lung and breast cancers.

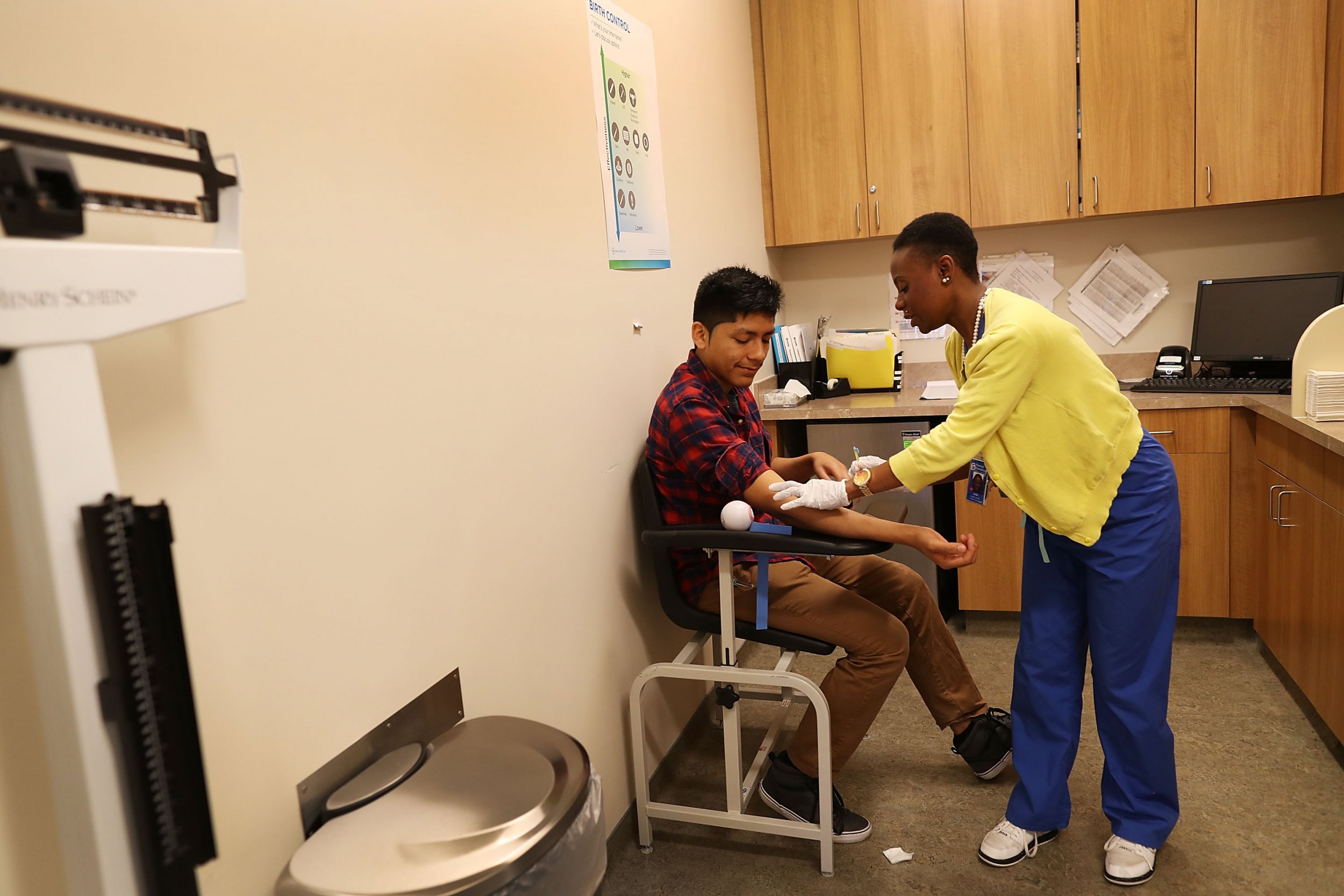

If these results are replicated in additional studies, people might someday receive the results of their "liquid biopsy" a few days or weeks after a simple blood draw.

Though the technology behind the test took years to refine, the basic concept is simple and bears some similarities to other blood-based cancer detection tests like the prostate specific antigen test, which is sometimes used to screen for prostate cancer. Both CancerSEEK and a PSA test look for proteins. But the PSA looks only for one kind; CancerSEEK looks looks for eight, and will also look for small pieces of DNA floating around in a person's blood. When these DNA fragments come from a tumor cell, it's called circulating tumor DNA; another term used has been cell-free DNA. The challenge is there are only a very, very small number of these ctDNA fragments to be found.

"It's really looking for the needle in the haystack," researcher Nickolas Papadopoulos told Newsweek. (Papadopoulos is a professor of oncology and pathology at The Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and led the research; he also is the founder of two cancer detection-oriented companies.)

Using both ctDNA and protein results together increases the test's overall accuracy. However, this is not a test that will detect every cancer, every time. Accuracy was higher for certain types of tumors, like ovarian and liver cancers, than they were for breast cancer, for example. The types of tumors included in this test account for about 60 percent of the deaths from cancer in the United States, according to the paper.

Based on the experiments, seven presumably healthy people would have been incorrectly told they might have cancer. However, that may not be the full story. "I would bet you, dollars to donuts, that those seven are not without cancer," said Dr. Mark Roschewski, a lymphoma researcher at the National Cancer Institute's Center for Cancer Research who was not involved in the study.

Given the grim outcomes that some people face if tumors are detected after they've already grown or spread, this test could be life-saving—if it works well enough.

"In solid tumors, earlier detection is actually the key. The earlier that one could detect a patient with a tumor, the more likely that the intervention would succeed because the intervention is surgery," Roschewski said.

Pancreatic cancer patients especially might have a better shot. Currently, the five-year survival rate for someone diagnosed with pancreatic cancer is 8.2 percent, according to the National Cancer Institute—and that number hasn't budged in decades. "Almost no systemic therapy we've ever given in pancreatic cancer works, not to an appreciable degree," Roschewski said. "The only way to cure pancreatic cancer with any certainty is resection. And the surgeries are not so easy."

The next set of studies might do well to recruit people who are at an increased risk of developing cancer and see if the test really can save people's lives through earlier detection, Roschewski said. These would include people who carry the BRCA2 genetic mutation, which has been linked with ovarian cancer risk, or people diagnosed with acid reflux or a condition called Barrett's esophagus, which may increase the risk of esophageal cancer.

Though the results are promising, there is still some room for improvement. First, all the people in this study with cancer had cancer that was detected some other way first. The results could be different if this test is used as a true first line of screening in people who seem healthy. And the test isn't as good as it could be for the earliest possible stages of cancer, Roschewski noted. CancerSEEK caught just under half of the cancers that were stage 1, the earliest possible stage, while the detection rates were higher for more advanced cases. (Additionally, this test only detects potential cancer cases; actually coming to a diagnosis would almost certainly require appropriate follow-up tests.)

Papadopoulos and his collaborators believe the test might cost $500 if it eventually comes to the market. Compared with the cost of treating advanced cancer, could this actually save the healthcare system money? Maybe—or maybe not, Roschewski noted. "Particularly when it comes to identifying what things should cost, we're particularly bad at that," he said. "But any time we're talking about curing people—not improving their overall survival, but about potentially curing people—that most of us believe the number of patients we actually cure will be cost-effective."

The test is not available yet, and it could be years until it comes to the market. "We want to kick the tires of this test," Papadopoulos said. However, if it does become widely available someday, Papadopoulos says he'll be sure to have it run on himself. "I do want to do it, and I will do it at the first opportunity."

This article has been updated to include information about potential avenues for research.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kate Sheridan is a science writer. She's previously written for STAT, Hakai Magazine, the Montreal Gazette, and other digital and ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.