Many clinicians and patients are frustrated and confused by the growing numbers of expert groups recommending women begin breast cancer screening later in life. This includes the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), a panel of government-appointed independent physicians that draws up guidelines on preventative care and screenings.

On Monday, the panel published new guidelines in the Annals of Internal Medicine recommending biennial mammograms for women age 50 to 74 who have an average risk for breast cancer. The USPSTF guidelines suggest breast cancer screening with mammography before age 50 has limited benefits, and conclude that more research is needed to assess whether women 75 and older actually benefit from the test.

In 2009, mammography guidelines became a subject of contentious debate when the USPSTF updated its breast cancer screening recommendations to suggest women undergo mammograms beginning at age 50 rather than 40 (as was previously recommended), and to do so every other year instead of annually. Despite widespread criticism and a large body of research on the life-saving benefits of mammography in the past half-decade, the task force has not backed down on that stance.

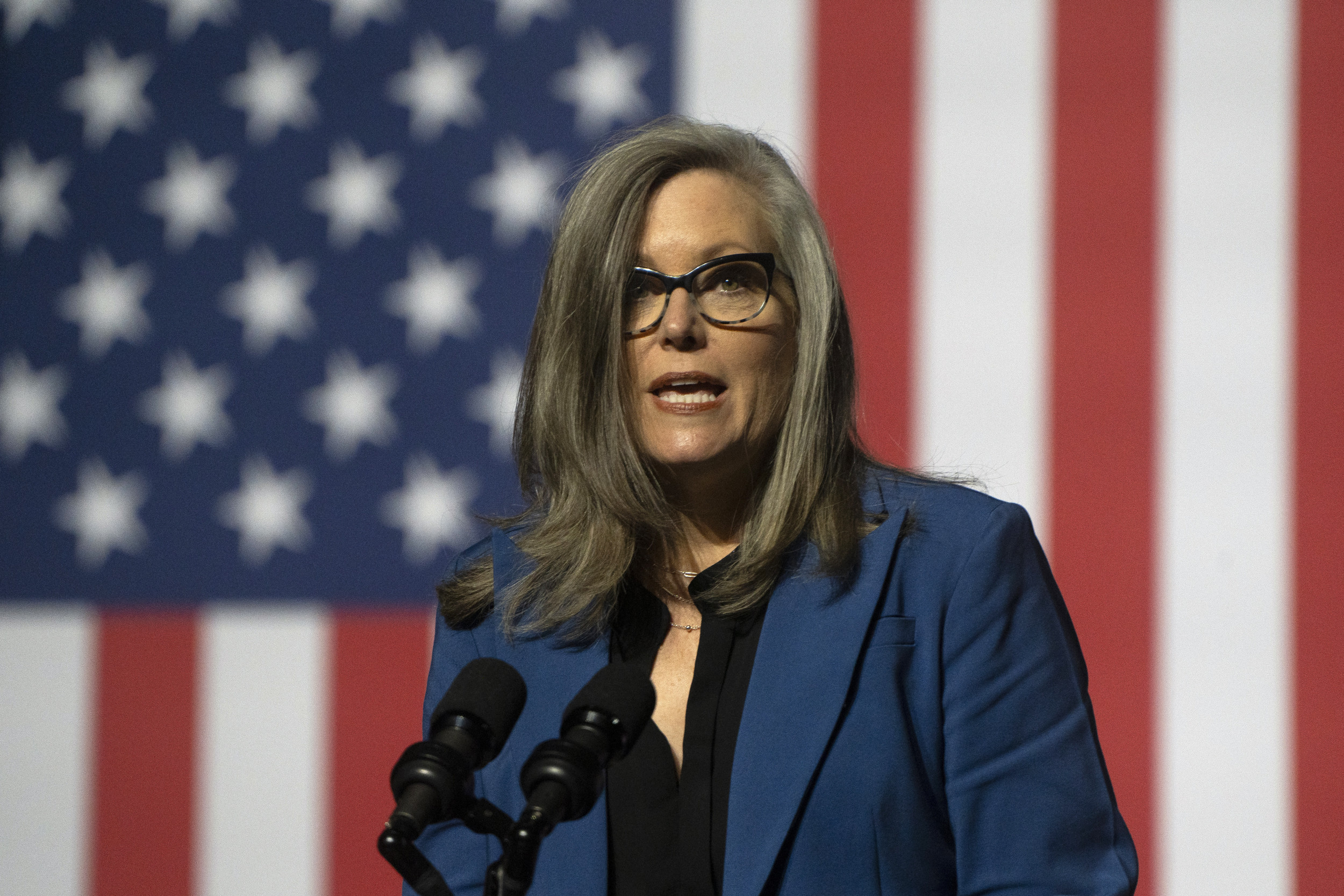

"The value of mammography increases with age, and older women derive the most benefit," says Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, vice chair of the task force. "The science absolutely supports the benefit of screening in their 40s, but the likelihood of benefit is less for women who are younger."

Over 230,000 women in the U.S. are diagnosed with invasive breast cancer each year, and approximately 11 percent are under age 45. Over the last several decades, breast cancer mortality rates have dropped significantly: Between 1975 and 2010, the number of women who died from the disease declined by 34 percent. That, says Dr. Susan Boolbol, chief of breast surgery at Mount Sinai Beth Israel, is primarily due to earlier treatment—which requires earlier detection. And, adds Boolbol, some public health care professionals are ignoring that fact.

"If we remove the early detection, do we lose ground in the area of medicine we've made so much progress in? That's very concerning," she says. "We will start to see more advanced breast cancer, which really has enormous implications: a higher number of patients needing to undergo more invasive treatment, such as a mastectomy instead of lumpectomy, or more-than-usual chemotherapy.

Though the task force's general guidance hasn't changed since it updated its guidelines about six years ago, Bibbins-Domingo says this time around she and her colleagues tried to emphasize that research does indicate screening in younger women has value, but just not for all women. She says the 2009 recommendations were "widely misinterpreted. "

The new guidelines say women in their 40s should make the decision to undergo early mammography based on a discussion with a physician about their health history and preferences. In particular, a woman with a sister, mother or daughter with a history of breast cancer may be a good candidate to start screening before age 50. These new guidelines were drawn up for women who have an average risk for breast cancer, and aren't meant for those who may have genetic factors—such as mutations to the BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 genes—that make her more like to develop breast cancer at some point in her lifetime.

However, many experts point out the problem is that approximately three-quarters of women who develop breast cancer don't have a history of the disease. In other words, many women who are seen as low risk for breast cancer can develop the disease.

One of the key reasons for the USPSTF's recommendation for later screenings is the potential harms of mammography. Studies have found that earlier screening increases rates of false positives and overdiagnosis, all of which can lead to undue stress and anxiety and in some cases unnecessary chemotherapy or surgery. Approximately 10 percent of women who undergo a mammogram will receive a false positive at some point in their lifetime. False positives are common in young women who are more likely to have dense breasts that make it challenging to differentiate between healthy and malignant breast tissue.

Other organizations have followed suit in revising recommendations. In October, the American Cancer Society (ACS) changed its stance on mammography. The organization now recommends woman with average risk for breast cancer begin annual mammography at 45 (their previous recommendation was 40) and move to biennial screening after turning 55. On the other hand, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) still recommends women start annual mammograms at 40.

Medical panels—especially the USPSTF— help to shape medical guidance and frequently inform health insurance coverage for certain tests. For example, under the Affordable Care Act, insurance companies are only required to cover screening tests for which the task force assigns a grade of A or B. (The panel assigns a letter grade to screening measures based on the strength of evidence, A through D, or "I," which means there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against.)

But on Monday, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued a statement that the task force's updated guidelines won't change mammography coverage. In December, President Obama signed a bill ensuring that women's coverage for mammography continues through 2017. The law requires women 40 years and older enrolled in most health insurance plans to be covered for mammography every one to two years without copays, coinsurance, or deductibles.

Still, many in the medical community worry that patients may struggle to make their own health care decision since influential organizations are publishing widely different recommendations that seem to be changing constantly. Later this month, the USPSTF, ACS and other organizations will convene for the first-ever Breast Cancer Screening Consensus Conference, organized by the ACOG, which they hope will be a forum to discuss streamlining recommendations.

Dr. Therese Bevers, medical director of MD Anderson's Cancer Prevention Program, says in order for the medical community to reach some consensus at the meeting, the USPSTF will need to back down on part of its stance. "They are going to have to acknowledge that women in their 40s are less likely to die from breast cancer if they get a mammogram," says Bevers. "They are also going to have to acknowledge that women are less likely to die if they have an annual rather than a biennial mammogram."

Bibbins-Domingo says that isn't going to happen. "We think that the discussion about the science is always helpful," she says. "But the task force has its own process, so nothing will happen in terms of our own recommendation statements. But we are very happy to participate in this."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jessica Firger is a staff writer at Newsweek, where she covers all things health. She previously worked as a health editor ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.