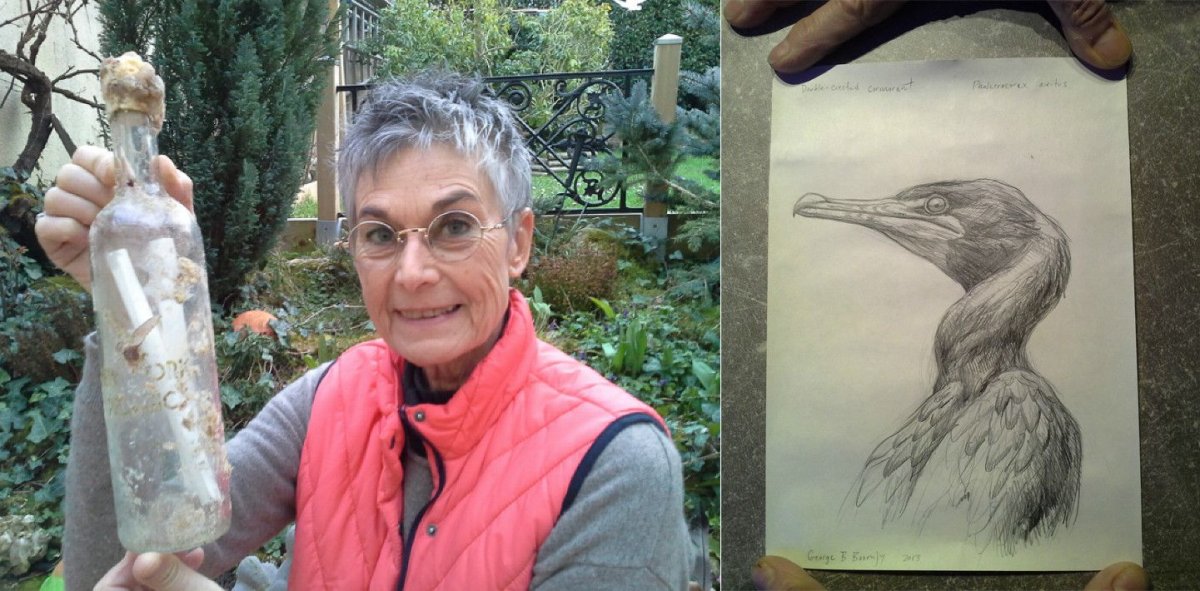

On February 17, Brigitte Barthelmy and her husband Alain took their dog, Elton, for a walk along a beach on the west coast of France, near the city of Royan. Brigitte, a painter, was searching for pieces of driftwood to decorate the couple's home when she came across a salt-, sand- and barnacle-encrusted wine bottle that had washed ashore. Inside were two scrolls, each bound with a piece of string. The words "New York Pelagic," with a bird standing in for the "Y" in "York," were etched onto the bottle's face. She took it home.

New York Pelagic, Brigitte soon found, is not a winery, but the name of a 5-year-old project by Brooklyn artist George Boorujy. "Pelagic" refers to the open ocean, an area of particular concern to the 42-year-old New Jersey native who went to the University of Miami to study marine biology before ditching the sciences to pursue an art degree. In 2010, when a large patch of garbage was discovered in the Atlantic Ocean, Boorujy came up with an interesting way to raise awareness.

After moving to New York, Boorujy became known for his large ink-on-paper drawings of landscapes and animals, which he depicted with a vivid, dramatic realism reminiscent of the Renaissance. The nature of Boorujy's art was nature under duress, weary and beaten down by the ceaselessly crashing waves of human industrialization. "I'm still interested in the exact same things," he says of his unconventional journey from one of the world's most prestigious marine science programs to the art world. "I'm just using a different methodology to explore those things."

The garbage patch is enormous, extending latitudinally from Cuba to Virginia, and in places contains up to 250,000 pieces of plastic per square mile. It is made up mostly of debris winnowed off of open air landfills, but also, of course, human litter. The pieces of plastic are small, most less a half inch in size, which means they are easy for pelagic wildlife to ingest. What worried Boorujy most about the patch, other than the wildlife it endangered, was that despite coverage in the media, it was difficult for people to understand the role they played in creating it. The issue has no real visual element able to capture the attention of the waste-creating public. This is where Boorujy felt he could be of service. "When I was thinking about how to make something visible and the idea of connection with the waterways, the next thought was, 'How can I get something into the water,' and before I even knew it, I was like, 'Message in a bottle.' It's such a cultural thing. There is a vernacular there. It's a trope."

Writing a message on a piece of paper, putting that message in a bottle, tossing that bottle into the ocean and hoping for the best dates back to Ancient Greece. The first known message in a bottle was jettisoned in 310 B.C. by the philosopher Theophrastus, who wanted to test whether the Atlantic Ocean flowed into the Mediterranean Sea. The practice continued as a means of scientific research into the 20th century. In the 1700s, Ben Franklin used drift bottles to chart the Gulf Stream. In the 1800s, the United States Geodetic Survey formalized the use of messages in bottles as a way to study the ocean. In 1910, George Parker Bidder of Britain's Marine Biological Association released more than 1,000 bottles to track the flow of deep sea currents. In 2015, while on vacation with her husband, a retired post office worker named Marianne Winkler found one of Bidder's bottles on the northern coast of Germany. It was the oldest such missive ever recovered. "It's always a joy when someone finds a message in a bottle on the beach," she told a local website.

Not all waterborne communiques are so practical and premeditated. Messages in bottles have been cast adrift as desperate cries for help, as well as final, poetic words of resignation left behind for the indifferent sea have its way with. As the Titanic sank in 1912, Irishman Jeremiah Burke quickly scribbled, "From Titanic, goodbye all, Burke of Glanmire, Cork," on a piece of paper and sealed it in a bottle his mother had given him before he left. It was found on the Irish coast a year later, miraculously only a few miles from his family's home. A few years later, in 1915, a passenger on the torpedoed Lusitania threw a message into the Atlantic that read, "Still on deck with a few people. The last boats have left. We are sinking fast. Some men near me are praying with a priest. The end is near. Maybe this note will—"

The author didn't have time to finish his thought. The ship sank in only 18 minutes.

Sometimes, such distressed pleas are answered. In 2005, a group of 88 South American refugees were left stranded by their traffickers on a disabled boat near Costa Rica. When they noticed the lines of a fishing boat, they attached a message in a bottle that read, "Help, please, help us." The message was received, the authorities were contacted and after three days at sea the refugees were rescued. In 2012, the crew of a ship hijacked by Somali pirates tossed out of a porthole a message in a bottle detailing their situation. It was recovered, and British and U.S. forces were able to convince the pirates to surrender. Just as lottery tickets are sometimes winners, messages in bottles are sometimes found. Hope remains hope, even if it is barely a flicker.

But for more than any other reason, messages in bottles have been cast for no logical reason at all. They are thrown into the ocean out of whimsy, out of curiosity, out of boredom. They are thrown by couples seeking a way to stamp their bond into nature—the nautical equivalent of carving initials into a tree—and by lonely, lovelorn souls, searching for serendipity. As Sting once sang about this very topic, "A year has passed since I wrote my note / But I should have known right from the start / Only hope can keep me together." The song ends with a cathartic realization. "Seems I'm not alone at being alone / A hundred billion castaways / Looking for a home."

Perhaps the most famous message in a bottle love story is that of World War I soldier Thomas Hughes, who in 1914 wrote a letter to his wife before going into battle, sealed it in a ginger beer bottle and dropped it in the English Channel. "Dear Wife, I am writing this note on this boat and dropping into the sea just to see if it will reach you," the letter began, before concluding, "Ta ta sweet, for the present. Your Hubby." Two days later, Hughes was killed, but the bottle continued to bob for another 85 years until it was discovered in 1999. His wife had died in 1979, but the artifact was returned to his 86-year-old daughter, who was only 2 when her father left for the war. "It touches me very deeply to know…that his passage reached a goal," she said.

This is the nature of messages in bottles, coming and going, missing their marks only to find them years later in ways the sender could have never anticipated. It's a romantic act, to use this form of communication that, though woefully unreliable, has such a delicious potential for magic. To send a bottle into the sea is to surrender a part of yourself to something larger, to something that may know what we don't know. How many meditations, specific and vague, have been tossed into the ocean, and how many of those doing the tossing have felt a faint pang of hope as soon as they drifted out of sight, one that at least for that moment was able to quell whatever curiosity caused them to throw the bottle in the first place? Every message in a bottle is a prayer.

When Boorujy was planning New York Pelagic, he considered recycling empty bottles he found on the beach himself before opting to make each New York Pelagic bottle a work of art in itself. "I wanted to explore this idea of value," he says. "Obviously we value disposable shitty plastic stuff because we produce and buy so much of it. But we don't think of those things as valuable. When we're done with them, they're a liability. They're garbage. But at one point, we put a really high value on them. I'm interested in the idea of throwing something that has a market value and is worth something into the water. I'm throwing it away."

After gathering some empty, clear bottles from a restaurant across the street from his house in Gowanus, Brooklyn, the notoriously polluted canal of which Boorujy affectionately describes as a colon emptying out into the ocean, he enlisted a friend to etch onto the bottles the title of the project. Inside each bottle Boorujy dropped a letter of congratulation to the recipient with information about the garbage patch, as well as a drawing of a sea bird. The bottles were corked and sealed with wax.

Using a "rudimentary familiarity" with tides and currents, Boorujy strategically selected times and places to send his art adrift. He hurled 19 bottles in all, most of them in 2011, and a few in 2012 and even fewer in 2013. He threw the final two bottles into the water off Staten Island in October of that year. It was one of these bottles that managed to negotiate its way into the open ocean and, 29 months later, into the hands of Brigitte Barthelmy.

"The bottle arrived in a perfect aspect…covered with shells," she wrote to Boorujy in broken English. "We was taking a walk on our beach, we was sad cause of the disaster of the 'tempest' the because looked like a 'poubelle.' ... My husband and me, we are going to contact the association concerned by the birds, and also by the 'no respect' of the environment."

She also contacted the French press, which became enamored with the story. Coincidentally, Boorujy started an Instagram account in January, weeks before the bottle was found. "This thing happened, and within a day all of my followers were French," he muses. This inspired him to comb through the notebooks he kept on the project and update his blog with stories of other bottles that had been found closer to where they were thrown. Boorujy insists he hadn't forgotten about the project, but given its middling, far-from-immediate results, it's only natural for his enthusiasm to have ebbed. "It's not that I hadn't given it much thought," he says. "I really enjoyed and loved it. It's just funny that this has taken off in its own little way."

More than anything, though, Brigitte's email inspired Boorujy as an artist. "You learn so much as an artist," he says. "If something happens, Yahtzee, great, good for you, you got something. But I think it sort of was like a reinforcement of a lesson of being a working artist in New York for the last 15 years that has been drilled into me for better or for worse. You just have to constantly work your butt off, and it may never amount to anything. You just have to keep doing it if you want to do it."

It's easy for artists to reassure themselves of this on an intellectual level, just as it is for those seeking love, or romance, or God, or some other sort of abstraction. But sometimes you need something else, some affirmation large or small that comes from somewhere other than yourself, that reminds you to keep searching, that you're on the right track. Boorujy may not have forgotten about New York Pelagic, but he needed Brigitte's email message. That was his affirmation. When he received it, he still had some unused bottles etched and ready for the ocean. He just didn't feel like he had a good reason to keep throwing them. Now, he has a reason. "I might even do one this weekend," he says.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Ryan Bort is a staff writer covering culture for Newsweek. Previously, he was a freelance writer and editor, and his ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.