One of the many tragedies of Nick Clegg's career in frontline politics is that he gave one of his best speeches just after it was over. On the morning of May 8, 2015, blinking on the edge of tears, the then-Liberal Democrat leader resigned in the wake of a calamitous general election defeat, before launching a defense of liberalism that shocked many people I knew: here was a man they had seen as bloodless at best suddenly speaking with verve of the convictions that drove him.

"This now brings our country to a very perilous point in our history, where grievance and fear combine to drive our different communities apart," he said. "And the cruellest irony of all is that it is exactly at this time that British liberalism, that fine, noble tradition that believes that we are stronger together and weaker apart, is more needed than ever before."

A year and a half later, I meet Clegg in his parliamentary office to talk about his new book, Politics: Between the Extremes. Part thesis, part mea culpa memoir, running through the text is the same idea that formed the backbone of his speech: that fighting for the liberal centrism he'd espoused as Liberal Democrat leader is of urgent importance. Where though, I ask, was that sort of soaring rhetoric during an election campaign that saw the Lib Dems define themselves rather meekly as a bolt-on to the other two main British parties?

"The first thing I'd say is my articulation of my own understanding of liberalism and defense of it, which I repeated on the day I resigned, is not something I hadn't done before," Clegg says, a little indignantly. But, he argues, "It's human nature that people don't listen to what people say all the time; they listen to what people say at heightened moments of drama." The post-election moment, he adds, was just such a moment: "You can't reproduce [that] in a speech to a think tank on a Tuesday morning, you just can't, however many soundbites you might try and furnish them with."

As Clegg tells it in his book, that gulf between the few snatched moments of a politician's life that the public sees, and the hours, days and weeks of work they don't, is central to understanding the Lib Dems' fall. He is open about his political naiveté in the early years of the coalition, writing, for example, that he underestimated the importance of visible "symbols of power" that underline a politician's status. Clegg had no recognizable location for his office, and David Cameron's office, he says, would not let him use the iconic door of Number 10 as a backdrop for public appearances. "In the absence of anything that visually demonstrated my authority, an impression soon formed that I was, in fact, bereft of authority," he writes. The Conservatives' talent for claiming responsibility for what were originally Lib Dem initiatives, such as raising the personal allowance on income tax, also had a part to play in undermining his position, he argues.

Talking to him, it strikes me that, just as privately charming George Osborne is unfortunately possessed of the face of a criminal mastermind, when Clegg isn't smiling or talking, something in the set of his eyes makes him look profoundly wobegone. It sounds petty, but during the coalition years the public image of Clegg as ineffectual was strengthened by the success of internet memes, including the "Nick Clegg looking sad" Tumblr, which did much what it said on the tin. (It gets a mention in the book, as it happens: "they could have added Nick Clegg looking fat, pale and unhealthy, too," he writes).

For Clegg, what he calls the "unconstrained cynicism about anyone in a position of authority," was also a factor. Where he saw the decision to enter coalition as a natural extension of his pragmatic, centrist politics, many people in the real world were keen to ascribe more self-serving motives, he adds.

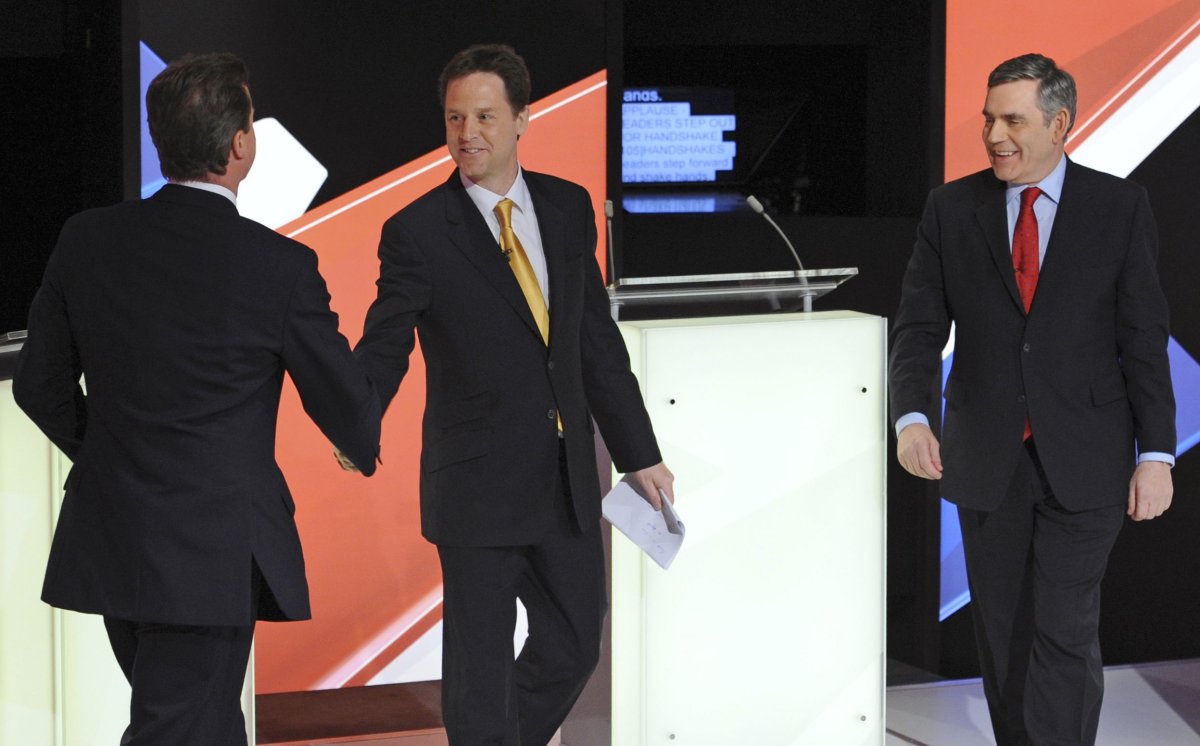

Here I pull him up. In the 2010 television election debate that sparked his breakout popularity with the public (dubbed "Cleggmania"), he made a virtue of his outsider status with a series of attacks on the Westminster establishment. "This is one area where I would like for once to see politicians put people before politics," he harrumphed, in response to one question on plans for public sector cuts. Isn't he guilty of fueling the kind of mistrust that he says makes balanced, rational government so difficult?

"I'm not sure I was whipping up a furore, but I was expressing something which I still share," he says. "What I said in that debate and I would say now if I had the chance again is: the system is not serving the people properly, and by golly it isn't." His attempts to change that system through constitutional reform are the subject of much soul-searching in his book. He concedes that, in both the failed referendum on introducing the Alternative Vote system and on many of his party's scuppered demands for House of Lords reform, the Lib Dems may have missed their window of opportunity. "Taking power away from powerful vested interests is the third rail of British politics: touch it and you get one hell of a shock," he writes.

The book is, in Clegg's understated way, scathing about supporters of Jeremy Corbyn, many of whom, he writes, are "more interested in self-expression than in government." I point out, though, that James Schneider, national organizer of Momentum, the campaign group that supports Corbyn's leadership, was once a prominent Lib Dem activist at Oxford University. Was the party Clegg led into coalition in 2010 more of a protest party than he banked on? "I did not anticipate that it would be as difficult, well, one could almost argue as impossible, as it proved to be to build an alliance of new voters from other parties," he says. Voters tempted but not swayed by the Lib Dems in 2010 often said they doubted the party's ability to govern, Clegg believes. He hoped by showing them that it could, the party would win them over. It didn't—in the 2015 election the party was reduced to eight seats from 57.

Reminded of Clegg's anti-establishment 2010 campaign, I'm keen to hear his view on the self-appointed rebel alliance of 2016: the "Leave" campaigners. "Well, they're now the establishment," he says, referring to the movement of Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson, Brexit Secretary David Davis and other prominent Brexit backers to the front benches. "They can't appear to reconcile themselves to their own victory; they've won! They've won! And to the victor go the spoils of victory…they now need to decide."

As a proud European who spent years working in Brussels and speaks five languages (one of several phone calls that interrupts our interview is conducted in Spanish), Clegg says he felt, "A mixture of anger, dismay, surprise and intense sorrow" when the result of the EU referendum was announced on June 24. "It was obvious how stark the generational division is," he says. "I just think that any country that takes a decision about its future against the explicit stated wishes of the people who have to inhabit that future is on the wrong path."

The anger, he says, is largely reserved for "the game playing within the Conservative Party that led to this." While at the time of the 2015 election he had not publicly ruled out joining a second coalition that promised a referendum on EU membership, he reveals now that privately he had decided he would not do so. "I realised that there was no way that David Cameron could wriggle out of this commitment to his party," he says, "and equally there was absolutely no way that I could ever consent to it, so I came to my own private view that I…me personally, I could never be part of a government built on what I thought was such a foolish referendum commitment."

As for Theresa May, the Remain-backing prime minister who now insists that "Brexit means Brexit" but seems short on any further detail, Clegg doesn't have high hopes. "I think this government is just going to descend into gridlock," he says. He sees a mismatch between "the kind of apparent pragmatism that Theresa May espouses in these early stages of the Brexit negotiations," and the Brexiters' "swivel-eyed view that we can return to 19th-century untrammelled parliamentary sovereignty."

Clegg says that the Tory party he entered coalition with changed rapidly and that he would have "paused for thought much more than we did" if he had known before making the deal that the Tories would become "regressive, angry, chauvinistic, anti-European." "We ended up strapped to an animal in coalition, a sort of political beast that just changed completely," he says.

But in his book he staunchly defends the decision to make the deal given the information—and the parliamentary arithmetic—available at the time. I suspect, I say, that even if the choice had been mathematically equal, he personally would always have plumped for the economically liberal, reformist David Cameron of 2010 over Gordon Brown, operator of what Clegg refers to in the book as the Labour Party "machine." "It was more an issue of almost timing and circumstance; inescapably a government that had been in power for 13 years feels less fresh and innovative and open minded," he says.

Now the Lib Dems' spokesperson on the European Union, the former deputy prime minister is not short of friends. Shirley Williams, the legendary Liberal Democrat peer, is sitting in Clegg's office chatting to his staff during our interview. His next appointment after me is lunch with Ken Clarke, a fellow liberal cast adrift in an illiberal age (though this one from the Conservative Party). In the book, Clegg writes of dining with Tony Blair, another political figure who has recently taken to theorizing about the future of the center ground. I ask if Clegg identifies with him. "Obviously he and I disagree: he doesn't believe in constitutional reform in the way that I do and I obviously disagree with what he did on Iraq," says Clegg, "but in terms of his belief that center ground politics is under threat and needs to be fought for, and argued for, and can't be resuscitated by just repeating left-wing nostrums of the 1970s? I strongly agree with him on that one."

Another thing Blair has taken to saying recently is that he no longer understands politics. Does Clegg, who has seen first his party and then the European Union he has supported so unwaveringly cast from the center of British public life, still understand politics? "I don't think anyone has a complete understanding but this book is a sort of early stab," he says. But in the book his tone is more certain. "A willingness to address deep-seated problems about the future is, in the end, far more persuasive than the tactical gamesmanship that disfigures modern politics," he writes. "It can be done. Reason, in the end, will win against unreason."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Josh is a staff writer covering Europe, including politics, policy, immigration and more.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.