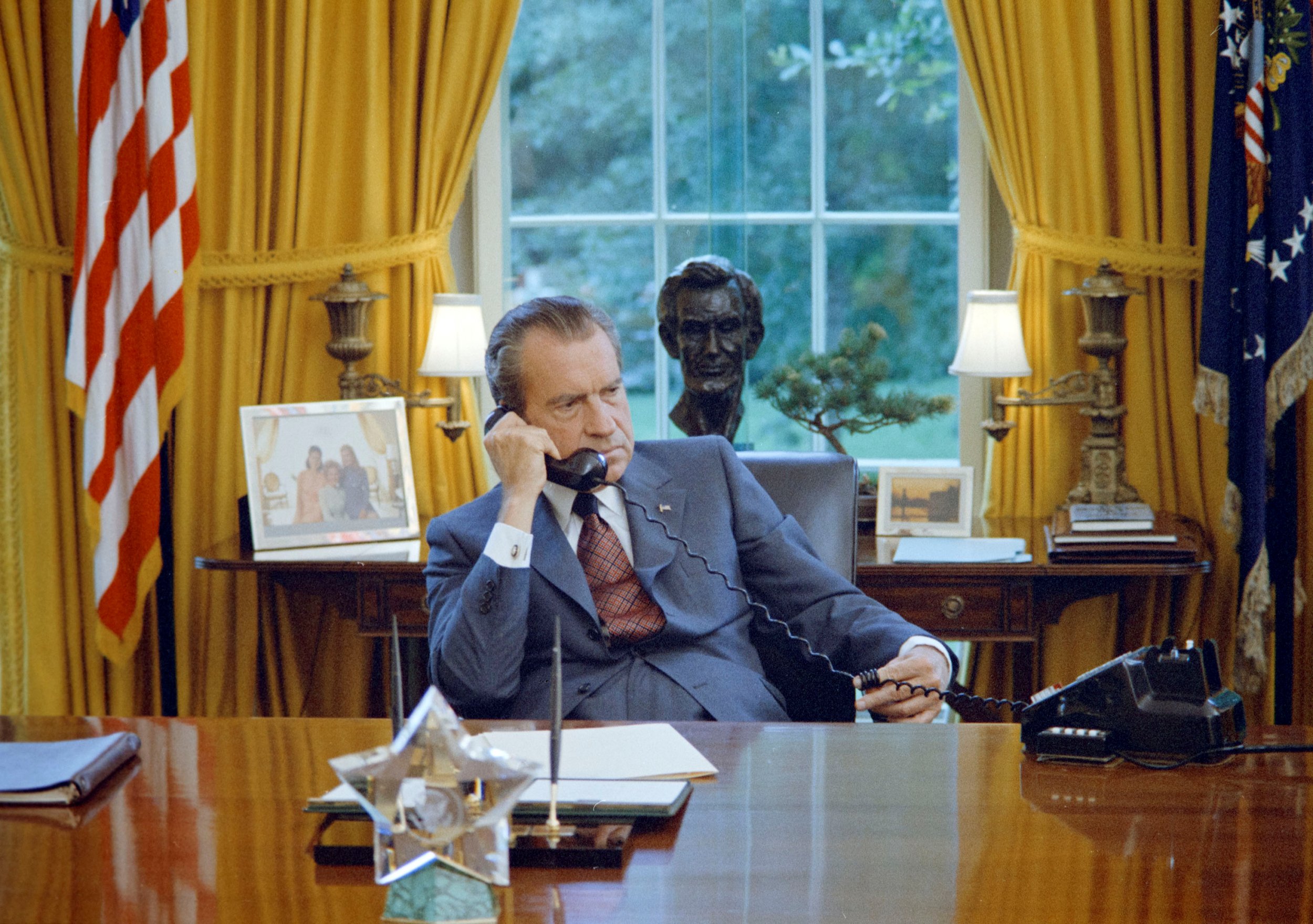

Newsweek published this story under the headline of "Was Justice Finally Done?" on January 13, 1975 after John N. Mitchell, H.R. Haldeman and John D. Ehrlichman were sentenced to prison for their role in the Watergate coverup, which saw President Richard Nixon eventually leave the White House in disgrace. In light of recent news involving President Donald Trump and a debate about his potential impeachment, however unlikely, Newsweek is republishing the story.

A jury of twelve ordinary Americans affirmed in law last week what events had long since made perfectly clear: that Richard Nixon's Presidency was the most pervasively corrupt in U.S. history. The witches' brew of scandal called Watergate had forced Nixon himself to abdicate and had generated criminal cases against more than 40 men, among them two Attorneys General, two Cabinet Secretaries, more than a dozen White House staffers and, by bitter coincidence, a Vice President. Yet the final day of reckoning in Judge John J. Sirica's Courtroom No. 2 was curiously wanting as the catharsis of a national tragedy. America's verdict on Watergate now is in. What remains to be answered is whether justice has been done - and whether anything of lasting value has been achieved. The first and most serious shortfall in the settling up was Nixon's absence from it. His pardon by President Ford had excused him from any criminal liability for the scandals, and ill health spared him from even having to appear at the trial to answer for his own actions. As a result, four more of his men now stand convicted and condemned to nearly certain prison sentences for a conspiracy in which Nixon was manifestly a participant - and for which he can never be brought to book. The anomaly did not finally sway the jury in the cover-up case, but it did give the verdict an edge of anticlimax, and it left the ledger sheet on Watergate incorrigibly out of balance. "San Clemente for Nixon," said one defense lawyer in a moment of off-the-record bitterness, "and San Quentin for everybody else."

Nor was the real denouement of Watergate settled with the verdict. The experience was one sense a vindication of the American system of self-government; an outlaw President was removed and his court brought to justice without revolution, or convulsion, or even very much visible pain. But reaching that end was a slow and imperfect process, and some others unasked. It fastened often on the mechanics of the cover-up more than on the abuses of power and influence that got covered. And it played out to on lies and evasions at the very summit of government; not even the men most intimately and prominently involved in the long pursuit of Nixon are now sure whether the legacy of Watergate will be a renewal of confidence or a deepening of cynicism among the governed.

The process did satisfy its first obligation to history: dixing Nixon's complicity beyond any but the most partisan doubts. Nixon quit a jump ahead of impeachment, and was pardoned before special prosecutor Leon Jaworski had decided whether or not to seek an indictment against him; the case accordingly will never be put to the test of proof in a formal adversary proceeding. But Nixon was an unindicted co-conspirator in U.S. v. Mitchell et al.; it became in long passages his own trial in absentia, and the evidence offered against his people - much of it in his own voice on 28 White House tapes - would have sustained a devastating prosecution case against him. The major elements:

Nixon had a demonstrable motive for the cover-up - first his re-election and finally his very survival as President. There was no direct evidence that Nixon knew of the Watergate bugging plan in advance, or that he directed the first frantic spasm of paper shredding and file burning; the eighteen-and-a-half minute erasure in a taped conversation on June 20, 1972, three days after the break-in, buzzed out his first known words on how he wanted the crise hadled. But other tapes show that he knew before the week was out that the burglary could be traced to the Committee for the Re-eelction of the President, and to his own resident black-operations man, E. Howard Hunt. "You open that scab," Nixon fretted to his chief of staff, H.R. [Bob] Haldeman, on June 23, "[and]there's a hell of a lot of things."

The tapes track Nixon's complicity to that day, and that motive. He and Haldeman settled early on that he would be insulated. "I'm not going to get that involved," said Nixon. "No sir, we don't want you to," said Haldeman, and sure enough, the hush-up to Election Day and beyond was transacted mainly by intermediaries like staff counsel John Dean and Nixon's private lawyer and fund raiser, Herbert Kalmbach. But the President kept in touch, complimenting Dean for having campaign, finally panicking when Dean strayed from the reservation and survival clearly became the issue. "You could get a resolution of impeachment," John Ehrlichman warned him in late April 1973, ". . . uh, on the ground that you committed a crime." Said Nixon bleakly: "Right."

Nixon tried to turn off the FBI Watergate inquiry during its critical first days. The June 23 tape - the "smoking pistol" that brought Nixon down - caught Haldeman warning Nixon that the FBI was "not under control" and was on the edge of tracing $1,500 found on the burglars through two devious laundry routes back to CRP. Together, the two men cobbled up an improvised counter-security grounds. "Don't lie to them to the extent to say there is no [White House] involvement," said Nixon, sending Haldeman off to carry out the errand, "but just say this is sort of a comedy of errors . . . Say that we wish for the country, don't go any further into this case." Haldeman sat down with the CIA that day and, with its intervention, stalled the FBI for two weeks - the crucial passage in which the first-stage cover-up got buttoned down.

Nixon assented to and finally directed offers to Executive clemency to keep potentially damaging witnesses in camp. The trial for the first time surfaced another damaging tape from the middle passage of the cover-up - a Jan. 8, 1973, conversation in which White House political operative Charles W. Colson warned the President that Hunt had some "very incriminating" tales to tell, and might start telling them if the White House abandoned him to the tender mercies of Maximum John Sirica. Nixon did not reject the notion of trading clemency for silence; on the contrary, he volunteered that mercy would be "simple" to justify, given Hunt's long service to the government and a series of family tragedies. "We'll build that son of a bitch up," said Nixon, "like nobody's business."

The tape by itself was not direct proof by guilt, since Colson had already flashed Hunt's a veiled OK, and Nixon in any case had said only that clemency could be granted - not that it would or should be. But the recording was of a piece with a Nixon pattern: clemency or pardons in exchange for cooperation in the cover-up. At one point, he had Ehrlichman make coded offers of clemency to his fall guys-designate, John Mitchell and Jeb Stuart Magruder, if they would only go quietly. ("I'd put in a couple of grace notes," Nixon coached, ". . . [about] the President's own great affection for you and your family . . . That's the way . . . the so-called clemency's got to be handled.") At another juncture, he proposed holding Dean in check with a reminder that only the President could restore him to the practice of law if things went wrong. At another stage still, he spoke grandly of full pardons for everyody involved - "That's what they have to have."

Nixon acquissced in payoffs to buy the silence of the seven original Watergate burglars. There is only fragmentary evidence suggesting that Nixon regularly kept up with the details of the back-stairs cash drops to the seven-an operation whose tab ultimately came to $429,500. But he patently did give his go-ahead to the last $75,000 payment to Hunt on March 21, 1973. In their notorious taped conversation of the late morning, Dean brought the bad news that Hunt was threatening to talk unless he got $120,000. Dean by then was coming down with a bad case of cold feet about his own involvement; Nixon and Haldeman later agreed in private that he had probably meant the message as a warning and that the last thing he expected was a green light from the President. A green light nevertheless was what he got. "Would you agree that is a buy-time thing, you better damn well get that done but fast?" pressed Nixon. Dean unhappily agreed that Hunt ought at least to get some signal, and the money went out that night.

In the weeks that followed, Nixon, thinking aloud, tried to get together a PR justification for the payments. "God dam it, the people are in jail, it's only right . . . [that] we do it out of compassion," he told Haldeman the morning after the Hunt drop, and later he offered Ehrlichman the "straight damn line" that the money wasn't to stop the defendants from talking at all - only to keep them from talking to the press. But both his men knew better, and told Nixon so. Haldeman, on the 22nd, reported having assented to payments out of a secret White House fund "when a guy had to have another $3,000 or something or he was gonna blow." And Ehrlichman, on April 14, conceded that the money had been raised and distributed among the seven "for the purpose of keeping them, quote, on the reservation, unquote."

Nixon had - and showed - guilty knowledge of the criminal acts committed by his people in his behalf. Nixon bottomed his defense on the contention that he was kept in the dark until Dean's "cancer on the Presidency" confessional of March 21. But the tapes confirm that he knew in substantial detail about the cover-up before them, and took no action to stop it either before or after that conversation. Dean in fact advised him beginning on the 17th that he, Haldeman, Mitchell and Colson were vulnerable to criminal charges, and that Magruder among other Nixon operatives had committed perjury. Nixon showed neither surprise nor anger, nor any impulse whatever to purge the guilty. Instead, he assigned Dean to do what he called a "self-serving" report clearing everybody, encouraged Mitchell to "stonewall it," left Magruder in a handsome government job and tutored Haldeman in the art of lying under oath without seeming to - "just be damned sure you say, 'I don't remember'."*

*Haldeman's response when questioned about the lesson at the trial: "I don't recall."

What housecleaning he did undertake was forced on him by the unraveling of the cover-up - and even then it started as a scrambling search for a sacrficial enchilada. "Who do you let down the tube?" Nixon asked Haldeman on March 22. In the days that followed, they nominated first Magruder (he went, but not quietly,) then Mitchell (he declined the honor) and finally Dean once he deserted and began the extraordinary series of confessions that ultimately brought Nixon down. But not even Dean sufficed, and it gradually came clear that Haldeman and Ehrlichman would have to go, too. Nixon tried to sweeten the news with an offer of $200,000 to $300,000 for their legal expenses apparently from a secret fund held by his chum C.G. (Bebe) Rebozo. "No strain," he stammered. "Doesn't come outa me." He did not say whether he intended the money as insurance of their continuing loyalty, and the two did not ask him; still, they discreetly turned him down.

With the unanimous judgment of the House Judiciary Committee, and now the fresh evidence laid out at the trial, the leading players in the long Watergate drama were mostly satisfied that the story of the cover-up has been told. There are still loose threads in the record - who erased the eighteen and a half minutes; who laundered some of the most damaging passages out of the White House transcripts; what Nixon's operatives hoped to learn by bugging Democratic headquarters in the first place. But Leon Jaworski, for one, now considers the mosaic complete except for a few "peripheral" details. So, for another, does James St. Clair, who ran the Nixon defense and abandoned it only on discovering that his client had deceived him. "No one will know every breath that breathed," he told NEWSWEEK's Stephan Lesher. "That's true of any human experience . . . but the key issues . . . now are known."

The haunting question for history was whether the cover-up really was the key issue. The name Watergate was a headline writer's convenience, a catch-word for the whole tangle of scandal revealed by the break-in - the political-police operations run from the White House, the misuse of government agencies to harass the President's political enemies, the implicit sale of government favor to his corporate friends. The cover-up came to stand for all of it, partly because if furnished the richest vein of evidence, partly because it involved clear and direct violations of the criminal code; St. Clair, for one, still believes that the impeachment inquiry was illegitimate to the extent that it ranged beyond that single, central crime. Yet the suspicion remains that some even more serious questions about the use and abuse of power got lost in the long march to judgment - that the shredded files and the perjured testimony became more important than the secrets they were meant to conceal.

The Nixon pardon seriously narrowed the scoped of the continuing inquiry into those secrets, and canted the scales of justice as well. The image of a President in prison is a profoundly idsquieting one for Americans; not many wished for so unhappy an ending to the affair. "He's in jail out there in San Clemente," said William Ruckelshaus, the former Deputy Attorney General who was cast out with special prosecutor Archibald Cox and A.G. Elliot Richardson in the Saturday Night Massacre of 1973. "I don't know how any man can be punished more."

Yet, as Ruckelshaus himself noted, the system of justice rests on the public perception that it is in fact just, and Ford's argument that Nixon had suffered enough by quitting has not wholly satisfied that first necessity. One consequence was the public spectacle of the subalterns imprisoned and fined for crimes in which the chief stands forever beyond the reach of the law. Another was to cheat history of a formal judgment that resignation of a President and no other way short of the trauma of impeachment for a government to fall. The conspiracy of silence, moreover, worked for enarly a year, swallowing up key documents and silencing key witnesses. It might never have been penetrated except for a fortuitous string of accidents - the assignment of the case to a hanging judge and to two hungry young Washington Post reporters; the tape ont he door latch that betrayed the burglars and the taping system that betrayed the President; the chance question that revealed the recording set-up, and the vanity of power that stayed Nixon from destroying the recordings on the spot.

Yet in the end the system did work, however fitfully and imperfectly; its vindication, in the eyes of the men involved, was that it got Nixon out. "One of the great advantages of the three separate branches of government," said Ehrlishment," said Ervin, "is that it's difficult to corrupt all three at the ast he perished of it. A President, said Cox in a recent speech in England, embodies all the nation's ideals of publice life, and strays from them only at his peril. "Woe betide him who sullies the nation's image of itself," he said. "In my view Watergate proved the conscience of the nation . . . [and] the ability of a self-governing people to vindicate, by the processes of open government, their own moral sense."

That conscience, once aroused, had a transforming impact on American public life, at least for a season; it was fitting that on the very day the cover-up jury rendered its verdict, a new Federal law went into effect limiting both campaign expenditures and private contributions in future Presidential campaigns. State legislatures around the nation have written or are considering equally stringent Nixon was or was not removed for good and sufficient cause; Richardson thouht that a better route for Ford would have been a decision against prosecuting - not an outright pardon - and that it ought to have been accompanied by a formal statement of the case against him. And most serious of all in the long term may have been the message to Nixon's successors that the loss of power will be deemed punishment enought even for its flagrant misuse. "Nobody I know wanted to see Nixon go to jail," said Sam Ervin, ". . . [but] there's an old saying that mercy but murders, pardoning those that kill."

Still, the pardon did not undo what the system had wrought: the unmaking of a President. The process was unwieldly, untidy and at points achingly slow; Nixon survived for 26 months after the break-in, and for fifteen after Dean first implicated him in May 1973. There were no road maps for the pursuers to follow - no precedent in history for the same time." Nixon challenged all three, and for a time held them at bay, even after they became privy to his guilty secrets. But Sirica and the Ervin committee opened the first cracks in the conspiracy; Cox, at the cost of his job, and Jaworski, at the risk of his, fought for the tapes; a unanimous Supreme Court forced Nixon to yield them; a committee fo the House of Representatives conquered its qualms and voted a bill of impeachment on prime-time network television. As a consequence, said Ervin's sometime chief committee counsel Samuel Dash, "Nixon is no longer President - not by any act of revolution but because the institutions of government worked."

They worked finally because an aroused public opinion forced them to, and some found in that single fact the most hopeful legacy of Watergate. Nixon fell because he believed his silent majority would permit him anything - would suffer his firing Cox, or stonewalling Congress, or resisting subpoenas, or pyramiding lies to sustain himself in office; it was the hubris of power, and at measures, and this time the politicians for once were running a jump ahead of the reformers. Electoral 1974 became the autumn of reform chic in American politics; it became commonplace for candidates to publish their tax returns, or to turn away big givers, or to equate incumbency - particularly Republican incumbency - with the moral ruin of Nixon's Washington.

Yet the reform spirit has always ebbed and flowed like the tides in the nation's political life, reaching its flood in the days of a Grant, a Harding or a Nixon, then dissipating in apathy and disillusion. American politics will be cleaner, so long as the post-Watergate ethos survives; Presidents will be more open and less imperious in the exercise of their power. But the resurgence of hope that attended the orderly resolution of Watergate runs in confluence with a deep cynicism born long before Watergate and nourished by it. The question now is which will prevail - hope or cynicism, confidence or despair. The court is America, and the jury is still out.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.